My Favorite Issue: Poetry and Nonviolence, 1979

Here we are in the 21st century where social relations are compromised. We live in states of exclusions from one another and refrain from attesting to states of ignorance that lead to violence. It is complicity that leaves wounds one can barely count. How do we come to know intellect, language skills, skin color, sexual identity, social status, and stories that challenge this disorder within this field of ignorance? The fabric of our civil discourse is fragmented, for the concepts of the common good and community based on equality and transformation are rendered inactive. Human relations are shaped by the realities of history and the struggles that convey how forces of oppression and domination maintain inequality, violence, and cruelty.

There is no one elixir, but I continue to recommend the power of poetry as a force field of human transformation to counteract verbal hypocrisy and the militarization of the mind. Poetry is intrinsically just because it is based on mutual con- sent between the poet and the one who engages the poem as a body, engages the one who suffers injustice in the small ways of everyday life and perhaps just needs to dive into the wreck- age of destruction, now more than ever bound to the future of existence on this planet.

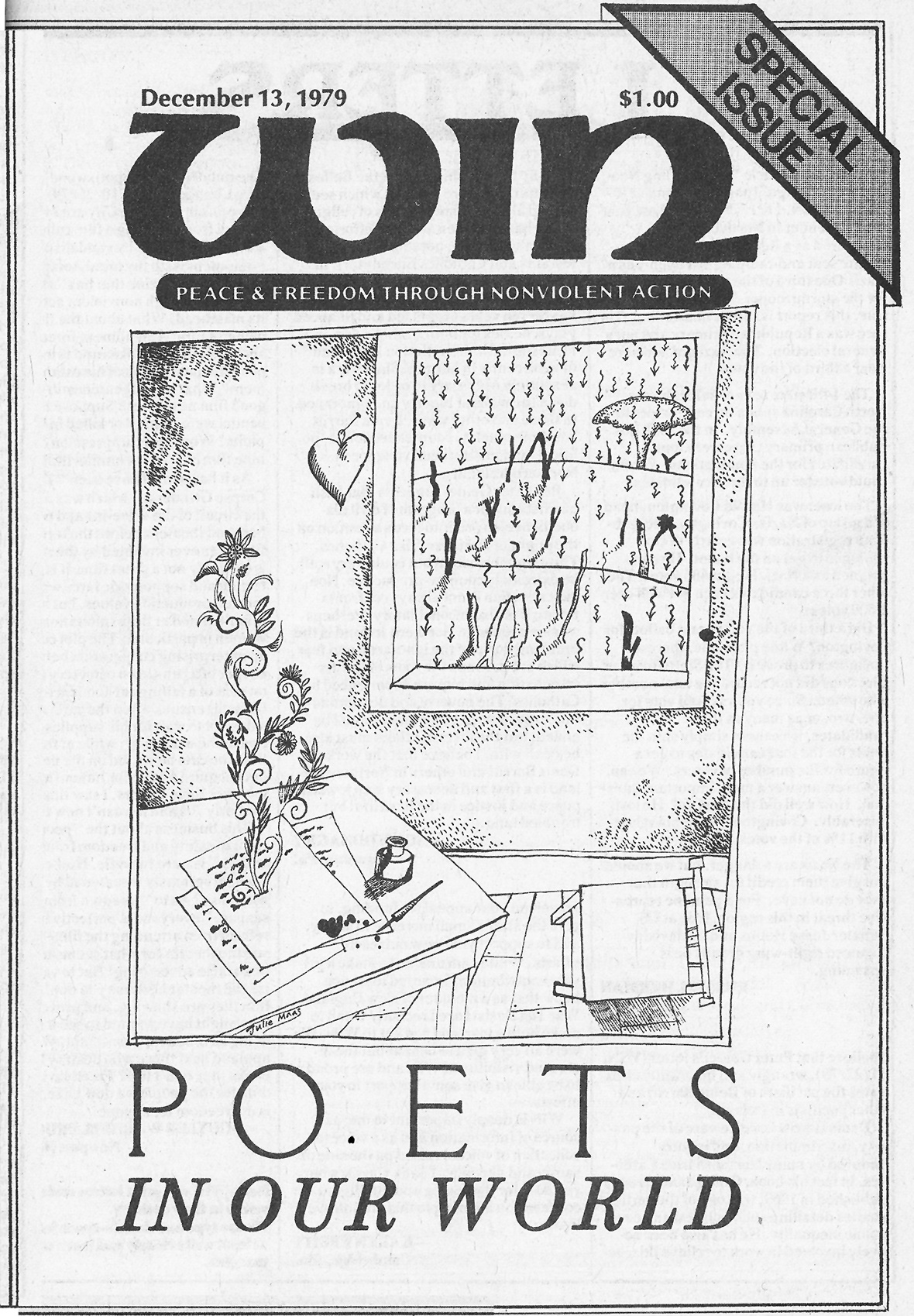

In 1979, I was a member of the editorial collective at WIN. From the top floor of a loft on Atlantic Avenue in downtown Brooklyn, we absorbed and printed the voices of the non- violent movement for peace and social justice, a goal beyond categories. Without the currency of social media, we were able to reach out across the globe with hard-working, relentless activists and theorists at the height of the antinuclear, anti- apartheid, antiracist, and feminist movements. It is my belief that what motivated us more than anything was the power to imagine a just world based on fearless speech. WIN was never about the singular “I.” It was about contesting, the interdepen- dent “we.” And our tools were those of language and nonviolent action, which challenges the passivity and submissiveness of the status quo. Yes, that was 35 years ago. Many of us are still at it, for it is a way of living.

In the fall of 1979, after the meltdown at Three Mile Island and the protests against Seabrook and Shoreham nuclear power plants, several of us attended a benefit called “Writers Opposed to Nuclear Power and Weapons” for the Shad Alliance, the War Resisters League, and Mobilization for Survival. It sparked an idea; we decided to publish renowned and younger poets who held forth that poetry weighs in at its his- torical moment and lives in it insofar as it remains the news of human life. Poetry is at the root of communication. Among the poets were Muriel Rukeyser, Jane Cooper, Joseph Bruchac and Peter Blue Cloud, Jean Valentine, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Grace Paley, ranging from Kathy Engel to Jan Barry to WIN staff members Mark Zuss and me. Those poets mentioned were our teachers, as we have become teachers to a younger generation in the 21st century. As Muriel Rukeyser said in her timeless essay book, The Life of Poetry: “But there is one kind of knowl- edge—infinitely precious, time-resistant more than monuments, here to be passed between the generations in any way it may be: never to be used. And that is poetry.” It was a radical idea to make a whole issue one of poetry. The news coming to us every day was so intense that we really had to sort out what to print, in a time of global/national urgency. We were being formed by the connective tissue we held amongst us from Brooklyn to the four corners of a growing movement.

Poetry often fell through the cracks of activism and, like seedlings in the cracked pavements of Brooklyn circa 1980, waited. For many of us, it lived in our nonviolent movement for social change. Poetry was not the foreigner. As it is today in spoken word and performance poetry by the younger genera- tion, it was a meeting place where those false barriers between us were and are taken down, stripped of their power. Poetry is of the people, and sometimes we might not want to hear about our faults, our deviations from revolutionary friendship. We are compelled via civil discourse to witness our own becoming in this place called America.

Poems say wake up, use language as weapons of nonviolent mass creation that see and hear and reconfigure Whitman’s “I singthebodyelectric.”Poemsshout,“Bringjusticetothevictims of systemic social injustice.“ Poems employ Satyagraha to speak language with the force of one’s entire body.

Denise Levertov speaks it forward in her poem, “Beginners,” published in this issue and dedicated to the memory of Karen Silkwood, who blew the whistle on faulty nuclear plant practices and paid for it with her “mysterious” death, and to Eliot Gralla, who had also died not long before the poem was published.

BEGINNERS

‘From too much love of living,

Hope and desire set free,

Even the weariest river

Winds somewhere to the sea—’But we have only begun

to love the earth.

We have only begun

to imagine the fullness of life.

How could we tire of hope?

—so much is in bud.

How can desire fail?

—we have only begun

to imagine justice and mercy,

only begun to envision

how it might be

to live as siblings with beast and flower,

not as oppressors.

Surely our river

cannot already be hastening

into the sea of nonbeing?

Surely it cannot

drag, in the silt,

all that is innocent?

Not yet, not yet—

there is too much broken

that must be mended,

too much hurt we have done to each other

that cannot yet be forgiven.

We have only begun to know

the power that is in us if we would join

our solitudes in the communion of struggle.

So much is unfolding that must

complete its gesture,

so much is in bud.

PRESCRIPTION FOR THE NOW

As I write this I have just returned from a compelling, con- tentious conference in Missoula, Montana, called Thinking Its Presence: The Racial Imaginary. Fellow writers and filmmakers pushed my understanding of white privilege and the incomplete conversation concerning the relationship between race and the imagination. Without doubt the reproduction of stereotypical intuitionalformsofviolencecensortheneedforopendialogue amongst all of us. Many of the stories and poems have been torn from the archives of history. These stories seize the trauma of history for all of us who live in this country.

I am a mature woman now. There are films and poems to stitch and share, but I want it to be a part of an opening to what is unfolding. The generations now writing at this time of collision and collusion against the imagination are being challenged by what Amiri Baraka calls the “motion of History.” In the 21st century, writers of color keep arriving on that nonstop train giving voice and sense to dialogues that need to continue to move off the page into direct and forceful activism. For as we know we think, we speak, we act, and the conflict between saying and do- ing has to be challenged and transformed by those who walked the rim of privilege and violence. It is now being done and it requires all of us to listen and read and walk the talk.

AIR TEXTURES

Nuclear winter begins In the gullies of aquifers

The testing grounds of the thermonuclear.

Evidence of the burn is found in follicles of the treeThe arsenals of thinking follow the laws of human consent

The geiger counter recalibrates plutonium, cesium

a tail winds circulate in pacific gyres

Sleeps in the screens of scripted dialogue

Out of terror

the familiarity of estrangement

is the book of rulesThe sonic impulse of water fragments into the hydroelectric

Mating rituals interrupted

What sings waggles in the dance of the bees

the landscape of the speaking eye

What whispers is ground to wind,

The stones of languages lost to human warSo why do I stay quiet in disenfranchised emergencies

That require no thought or obligation

Why do I avoid the knowledge that blue corn comes from the sun?Remote sensing is beyond a large screen tv

It marks the surface of your lover’s body who knows consent or violation

The beauty of resonance where forgiveness is unspoken.

The children who sing forth that song in its desperate longing.Are they themselves violated?

They walk to the unknown of sensing.

As chains of tyranny target.— Mary Jane Sullivan