My Favorite Issue: WIN No. 200, 1974

Here’s what I think when I remember the 200th issue of WIN magazine:

We were right.

It is the conventional wisdom of many in today’s popular culture that the antiwar hippie movement was a monumental failure. It was, they say, the precursor to the selfishness of the “Me Decade” that followed.

They are wrong.

I first became aware of WIN in 1968, when I was 15 years old, a freshman at a girls’ boarding school in Connecticut. It had only been a year or so since I decided I was a pacifist. Through one of my friends, I discovered the War Resisters League, and, through WRL, WIN.

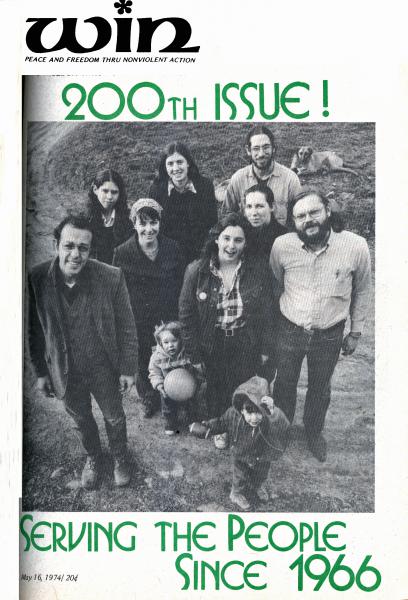

My tenure as a staff-person at WIN was brief, from early 1974 to mid-1975. This happened during the time WIN had moved to upstate New York, onto a small farm near Kingston, and almost all the staff lived and worked together. There were two buildings, a farmhouse and a converted barn. The barn had bedrooms, the office, and chickens on the ground level. For a time, we had a goat. There was a housecat, Ho Chi, and barn cats, Matilda and Hillary.

If you believe the popular narrative, communes were places for maniacal and charismatic leaders to brainwash their supplicants. The social structure would be dominated by a religious zeal, one that encouraged participants to abandon their fami- lies and ignore the outside world.

We weren’t like that. We had a magazine to produce every week, without fail. And we did, except for a few rare double- issues that let us skip a week.

The 200th issue was special because it was about us.

It shows what life on our commune was really like, as much as paper is able to do. There are pictures of our friends and neighbors and contributors, both local and around the globe.

Besides this photo gallery, there is a two-part story describing a typical week in the life of the staff. I wrote the first part of it, and editor Maris Cakars wrote the second.

Back in those days, putting together a magazine was hands-on work. Every word was typeset on a typewriter. Every image was printed on paper. The printed papers were then cut up and pasted on cardboards, to be sent to a printer in the city, who would also do the mailing. To be an editor on staff at that time, one had to be able not only to edit and proofread, but to use rubber cement and a straight-edge. Reading the description of what we did, I’m struck by the fact that we spent at least three days doing things that today could be done in an afternoon with a two-year-old iMac.

I’m also struck by the description of the editorial process. Three of the men who worked on the magazine — Maris, along with Marty Jezer and Fred Rosen — selected the feature stories. Marty (and, later on, I) would edit the news section. I edited the arts section, and Susan Cakars did the letters. In other words, men made almost all of the editorial decisions. My memory is that it was more of a consensus process involving the entire staff. My memory might be fogged by nostalgia.

Along with putting out a weekly magazine, we had a garden, where we grew vegetables. With the chickens and the goat, this meant there were always chores to do. I found that, when something irked me, I could go outside and rip up a few weeds and feel better. Weeding was also good for writer’s block. I might not be able to form a beautiful sentence, but I could clean up a row of tomatoes while I worked that out.

We had about 10,000 subscribers at that time, and I felt like I knew almost all of them. Not because we got that much mail (although sometimes, we did) but because we did all of our fund appeals by hand. We stuffed envelopes and stuck the printed labels on every piece. We noticed when there were new names, and when familiar names dropped off.

Our days were not drug-filled orgies the way modern pop culture would have you believe (or, if they were, I wasn’t invited). We had a rhythm to our tasks, and to our little joys. We liked to read the mail. We liked to play board games. I’ve always said you haven’t lived until you’ve played Monopoly with socialists and Risk with pacifists. It brings out all those repressed impulses without causing any actual damage.

We got to watch Nixon resign. We laughed when President Gerald Ford proclaimed he would “Whip Inflation Now” because it meant we could get promotional materials using those initials quite easily and inexpensively for our own supporters. We knew the FBI was checking us out, not only because of our antiwar activities, but also because they thought that maybe we were hiding Patty Hearst. I mean, all communes are the same, right?

We weren’t the Symbionese Liberation Army. We weren’t the Manson Family. We were friends and family who shared a common goal: to end the war, keep the peace movement connected, and maybe, just maybe, grow some corn.