WRL Volunteers: Mid Century

WRL never had enough staff to accomplish all its work, so volunteers regularly contributed time and skills. When it was founded in 1923, the volunteers were mainly well-educated and financially-comfortable women who had known each other previously from peace activities to end World War I. In the World War II era, when men involved with WRL were away in conscientious objector camps or prison, volunteers, some parents of resisters, augmented the staff of post draft-age men and women. Later, volunteers comprised a more eclectic group.

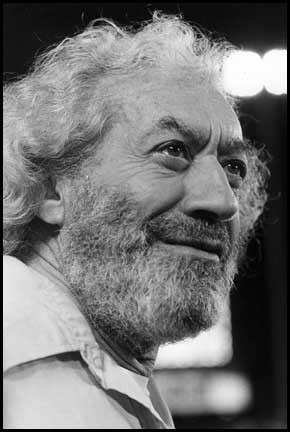

Returning from imprisonment as a draft resister, and for the next 40+ years, Jim Peck became the most famous volunteer. Independently wealthy, he always referred to himself as a volunteer though working full time, and contributed funds instead of drawing a salary. He edited the WRL News, managed the mailing list, draft counseled, and still managed to be arrested for nonviolent civil disobedience over 50 times.

The Vietnam War brought an influx of people eager to contribute their time. I, for example, spent many evenings at the 5 Beekman Street office typing fund appeals while older men silently marched passed me to attend meetings. Very excited to type letters to leftwing celebrities, I didn’t realize until years later that those men should have at least acknowledged my presence.

By the time WRL moved to the Peace Pentagon in 1969, a more sensitive process for handling the volunteers was in place, headed by staffer Ralph DiGia and supported by me, now on staff. Ralph also made volunteers feel welcome and appreciated. There was a large, if drafty workroom, with long tables for envelope stuffing, and every fund appeal, newsletter, and call to action had to be hand stuffed and stamped. Ralph had an amazingly efficient system and dexterous volunteers could stuff 500 envelopes an hour.

And he was also a taskmaster, especially when we were trying to mail out late-arriving calendars (see the Calendar Overview blog). While someone always brought beer to keep volunteers happy, he would try to curtail our drinking it because it would make us stop to pee too often. Some thought he was joking…

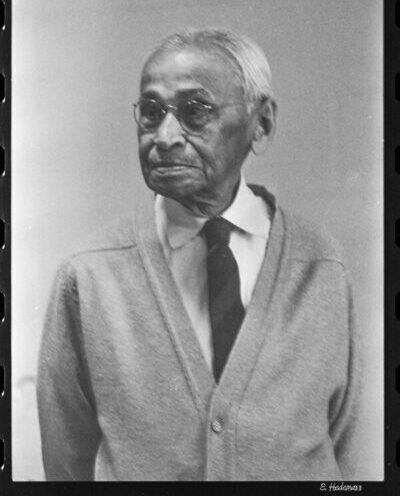

Several volunteers came nearly every day, such as Prafulla Mukerji, who had been on some of Gandhi’s campaigns.

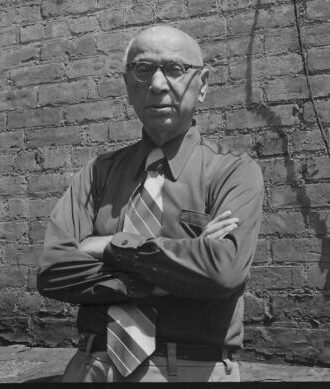

David Berkinghoff, a jailed World War I resister, traveled from The Bronx where he was part of the Jewish Socialist Bund. Because a pacificist life has its weirdnesses, at David’s memorial Jim Peck got into a debate with another mourner who claimed that David was a zionist while Jim asserted (correctly) that David supported Palestinian rights.

A sweet retired shoemaker was also a regular volunteer. He and Ralph shared a love of Italian opera so the workroom was often filled with its sounds. Unbelievably, his wife left him when he was diagnosed with cancer so Ralph, among other WRLers, visited him often and helped with his care.

Another early ’70s daily volunteer turned out to be quite different from the others. Henry was 40ish, seemed to have no job, lived with his mother in Queens, and daily brought a lunch she had packed. Then he disappeared. It turned out that he was an FBI informer, relaying workroom conversations to agents, some of whom, in bad disguises, were stationed across the street. Years later, Henry surfaced on the local TV news, in front of his mother’s house, as an anti-abortion proponent. He subsequently signed a petition supporting “even extreme violence” to end abortions. However, when he was still passing his days in the workroom, it didn’t matter that he was dumb and weird—he had two hands for stuffing and Ralph kept him busy. We needed all the help we could get.

– Wendy Schwartz

An activist with WRL for over 50 years focused on the role of women in the organization and everywhere, Wendy Schwartz is proud to have crafted WRL’s statement on freedom of choice.

Share