Spring 1972: Blockades by the Bay and the June 10th New Jersey Action

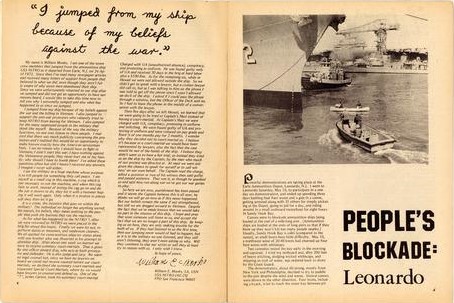

In Spring 1972 People’s Blockades sprang up around the country. Their goal was to prevent munitions from leaving U.S. ports for Vietnam.

One target of the blockade was Earle Naval Ammunitions Depot, located in New Jersey on Sandy Hook Bay, with multiple types of actions involving several pacifist organizations and more than a hundred activists. Residents of the nearby towns, afraid that closure of the depot would devastate their livelihood and angry at being “invaded by outside agitators,” harassed and fire-hosed demonstrators, and sabotaged their cars. In retrospect, as the peace movement did in other circumstances, we should have responded more sensitively to their concerns, possibly, even offering ways to produce income not dependent on the military. At the time, though, our focus was solely on ending the war.

In April, 21 demonstrators were arrested while trying to prevent the loading of an ammunitions ship. In May, on rough waters, demonstrators in canoes attempted but failed to reach the ship. At least one, whose boat capsized, became ill from swallowing bay water.

I joined the demonstrations on June 10th. One group protested outside the main gates of the military facility. The other—mine—protested on, and prayed at, the railroad tracks leading to the dock. These were legal demonstrations, but most of us were rounded up anyway. Unfortunately, a young woman from the community, walking nearby, was also arrested and she faced consequences not only from the authorities but from her pro-war family.

Because of the military installation in its jurisdiction, the police had access to federal data and thus discovered that several among us had a significant history of civil disobedience arrests. This made the police even less happy about our presence, and it led to our being locked up with bail set.

We had not planned on spending time in jail and most wanted to be bailed out, so I had an un-arrested demonstrator phone my father. Since it was a Saturday, he would have had a lot of cash on hand in the family produce store. My father’s very difficult life left no room for developing strong feelings about the Vietnam War, but he didn’t approve of my professional career as an activist and believed the police generally did the right thing. But he never turned his back on a need, and his money was needed in Leonardo. So he drove south from upper Manhattan for over an hour to the lockup where I was. He paid my bail and then watched with wide eyes as I opened an envelope containing the possessions removed when I was arrested: a belt, shoelaces, and earrings. “They took them from you?” he asked incredulously.

My father then told an officer he wanted to bail out as many more demonstrators as he could, but was refused. I could see his anger rising as he started to speak. But the officer cut him off, saying in a tone that suggested he didn’t believe it, that one demonstrator “said he was sick” and we could have him if we wanted. Both of us jumped at this offer.

It turned out that the demonstrators were held in several different locations and the police wouldn’t say where the sick demonstrator was. So we had to hit three before we found him. My father plunked down some cash and a man I knew well, suffering a severe asthma attack, was released to us. He was gasping and quite green. But, his anxiety relieved, he perked up in the night air, and we set off toward his home in Brooklyn. In the car, my father’s education about nonviolence, the peace movement, and Catholic radicalism really began. He listened attentively and sympathetically to what a 30-something man said, having previously dismissed similar arguments from me, a mere 20-something girl.

Fortunately, the Civil Liberties Union of New Jersey took our case. On a rainy November day, the June 10th brigade rode a chartered bus back to Leonardo for our trial.

In the end, the verdicts were mixed for all who participated in the spring demonstrations. My group initially was fined, but a few demonstrators refused to pay the fine and spent 15 days in the Monmouth County Jail. Later, the verdict was overturned. Joanne Sheehan, who did the jail time, lamented recently: “I wanted credit for my 15 days, still waiting…”

—Wendy Schwartz

Wendy Schwartz has been a pacifist activist with WRL for more than half a century.

She is now trying to figure out what she, or anyone, can possibly do to end Israeli’s attempts at genocide of the Palestinian people.

Share