A Death in the Family: David McReynolds, Pacifist, Socialist, Ailurophile

As WRL reflects on David’s life and legacy, heading into our 95th year of radically resisting war, we’re humbled and grateful for the kind of politic David brought to our movement + organizational spaces. To make a gift to WRL in David’s honor, click here. To write a message of remembrance for David in our 95th Anniversary program journal, click here.

By Judith Mahoney Pasternak

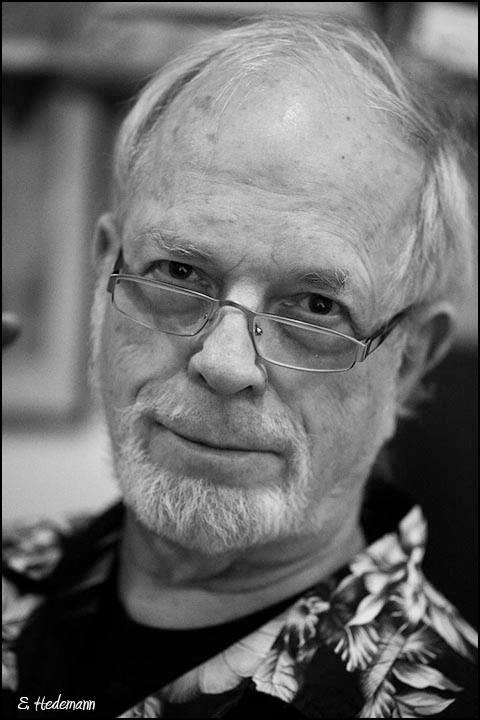

A great force for a peaceful world left the planet when WRL’s—and the nation’s—David McReynolds, who for decades was the best-known voice of American radical pacifism, died August 17 of injuries from a fall in his East Village home. He was 88 and had spent almost 40 years on the staff of the War Resisters League as a self-described “movement bureaucrat.” He ran for the presidency, for Congress, and for the Senate, traveled the world promoting nonviolent resistance, wrote one book and innumerable articles, memos and pamphlets, came out as gay long before most people in public life did, and documented the movements of his time in indelible photographs. He was one of the last (and youngest) of a heroic generation of pacifists who resisted war and militarism between World War II and the Vietnam War and went on to help forge a vibrant peace movement in the aftermath of the wars.

Life Before WRL

Born in 1929 into a comfortable Baptist family in Los Angeles, David early on evinced his commitment to pacifism and Marxism, saying much later that he “didn’t see how one could be one without being the other.” Equally apparent by his adolescence, if not before, were the outsize contradictions that would characterize his adult life. A tall, gangling teenager, aware of his homosexuality from the age of ten and, as he later wrote, “haunted” by it, in high school he joined the World Fellowship Club to oppose U.S. Cold War policies. (It may have been that early that the FBI began keeping the files on him, 400 pages of which he later acquired via the Freedom of Information Act.) A few years later, at UCLA, he became, of all things, a proponent of, and propagandist for, temperance with the youth branch of the Prohibition Party.

More significantly, however, it was also at UCLA that he joined the Socialist Party. And it was there too that in 1949 he first heard the charismatic World War II conscientious objector Bayard Rustin speak. Rustin (1912-1987), then the organizer for race relations with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, became David’s “existential hero” on the spot. In 1953, the year he graduated from UCLA with a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science, Rustin was serving a 60-day jail sentence in Pasadena for a then-illegal homosexual encounter, and David visited him in jail. When FOR fired Rustin upon his release, he moved to New York, where the War Resisters League, undeterred by his conviction, hired him as its executive director. (Later, on leave from WRL, he was the chief organizer for the historic 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Justice.)

In 1956, Rustin was among the group of pacifists who founded Liberation magazine, which was loosely affiliated with WRL and which rapidly became a major voice of the New Left. A year later, in response to an apparent job opportunity at Liberation, David left California for New York. The job was gone when he got there, but the post of editorial secretary became available soon after, and David got it. He worked there until 1960, a period he later described as “three years of weekly meetings in Greenwich Village that began at 4:00 p.m. and ran until 9:00 or 10:00 p.m., usually broken by dinner at the Blue Mill Tavern, with Liberation board members A.J. Muste, Ralph DiGia, Bayard Rustin, Dave Dellinger, and sometimes Paul Goodman or Barbara Deming.” Those people were at the time the New York luminaries of American pacifism. They influenced him profoundly; some would be his friends and colleagues for the rest of their lives. Muste (1885-1967) was the labor organizer and minister who became David’s most important mentor, and Rustin and DiGia (1914-2008) would be his colleagues at WRL. Unlike many of those mentors and colleagues, David never served years in federal prison—he had been arrested in 1954 for refusing induction into the military, but the charge had eventually been dropped, and he was classified as a conscientious objector. He did serve countless short stays in jail for civil disobedience, and he did commit at least one federal felony: He burned a draft card in 1965 as a protest against the war in Vietnam. (Rumor has always had it that the card wasn’t his own, and in any case, he was not only a CO but 35 and past draft age at the time.)

Not long after he got to New York, he moved into an apartment at 60 East Fourth Street, in what came to be known as the East Village; he lived in the building for the rest of his life, moving only from a higher floor to the ground floor in his last years. It was in that home that over the next six decades he followed the wide-ranging personal interests that were almost as central to his life as the causes he worked. Shaman, the cat who sat next to David after his fall, was the last of the many Siamese who had been his live-in companions, usually two at a time. He joined the New York Bromeliad Society to learn more about the culture and care of that plant family, He was an ardent lover of jazz and classical music.

WRL …

In 1960 David left Liberation to become the field organizer at WRL’s office at 5 Beekman Street. He would on the WRL staff for almost 40 years, never changing jobs again; over time, he became the public face of the organization. During his early years, Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day (1897-1980) and others were protesting annually in New York’s City Hall Park against the then-current practice of mandated “civil defense drills” that required pedestrians to take shelter from potential atom bombs. One of his first organizing triumphs was publicizing the protests so that, ultimately, instead of a handful, some 2,500 people refused to take shelter, after which the city canceled the drills. (Before the cancellation, David had served 25 days in jail for not taking shelter during one of the protests.)

A few years later, WRL took on co-publication of WIN magazine, which had been founded in 1966 by the New York Workshop in Nonviolence. Unlike Liberation, WIN was explicitly committed to pacifism and nonviolence, and from then on David’s writing would appear primarily in WIN. He wrote—and spoke to the media—on a vast range of subjects, once summed up by a colleague as, “former Yugoslavia, Iraq, government spending priorities, or the evolution of the United States from a small nation with an isolationist foreign policy and anti-militarist traditions to the status of sole superpower with the world’s largest standing army and a nuclear arsenal capable of global holocaust.” Another staffer wrote, “He could always see the forest as well as the trees, because his internationalist vision and class analysis helped us see the connections between militarism at home and militarism abroad “ Supplementing his job-description responsibilities, in 1968 he ran for elective office for the first time—for Congress, on the Peace & Freedom Party ticket (ticket headed by Cleaver)

In those early years, a major focus of WRL and a significant part of David’s job was organizing against and protesting the war in Vietnam. One night in 1969. the Beekman Street office was ransacked by a perpetrator who was never identified. Not long afterward, WRL moved out of there and into a building at 339 Lafayette Street, which it then purchased. After the purchase, with David leading the way, WRL members created the A.J. Muste Memorial Institute, a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt nonprofit, which ultimately bought the building and rented spaces in it to other peace and justice groups; the building soon became known far and wide as the “Peace Pentagon.” David would serve as the institute’s chair in the 1980s and on its board until 2015.

But the Vietnam War was by no means WRL’s, WIN‘s, or David’s, sole focus. In 1969, the same year as the raid and the move to Lafayette Street, WIN published an issue on Gay Liberation—and David seized the moment to, as he later wrote, “be honest at last”: In a piece he titled “Notes for a More Coherent Article,” he came out publicly as homosexual. (Looking back in a later incarnation of WIN in 2015, he wrote, “I never even liked the term ‘gay,’ as I didn’t, in my experience, find that much about it that was gay.”) The next year, that article was included in a collection of his work, We Have Been Invaded by the 21st Century (Praeger, 1970). (It was in WIN ‘s successor magazine, the Nonviolent Activist, that he would write in 1992 what may have been his most controversial article ever, a passionate argument against vegetarianism entitled “Vegetarians and the Totalitarian Mind,” addressed to an audience that has a far higher proportion of vegetarians than does the general public. It was not the first or last time his outspokenness would get him into trouble.°

He visited North Vietnam (illegally) twice during the war. When the war ended, much of the peace movement, including David and WRL, turned to working for nuclear disarmament. In 1978 he protested nuclear arms in Moscow’s Red Square with six other WRL activists while 11 others protested simultaneously on the White House lawn. (The White House demonstrators were arrested, the Moscow ones were only “escorted” out of Red Square.) He ran for the presidency in 1980. And week in and week out, he spoke wherever anyone asked him to on the necessity for nonviolence and the possibility of democratic socialism. As he approached his 70th birthday, however, it occurred to him (if not to others) that he might not be able to maintain that position forever, and he decided to retire as of January 1 1999, without waiting for the fortieth anniversary of his WRL tenure.

… and Beyond

That spring’s issue of the Nonviolent Activist was devoted to a celebration of his career, and in May, WRL threw a gala farewell event honoring his incalculable contribution to the cause of peace and to the organization. Barbara Ehrenreich, writer and “myth-buster” (her own title for herself), delivered the keynote speech. However, as David wrote in the magazine, “Of course, radicals don’t actually retire. This is not a job like any other. Unless our beliefs change, we hold steady to whatever course we had set, writing, speaking when asked, joining demonstrations and direct actions, attending meetings (but surely, dear God, fewer committee meetings).”

He did hold steady to all of the above—and more, running again for the presidency the next year (again on the Socialist Party ticket). So there weren’t even, at first, fewer committee meetings. He remained on the Muste board until 2015. There were still speaking engagements, article requests, and, sadly, increasing numbers of funerals. He and former WRL Office Coordinator Ruth Benn began digitizing and archiving his immense collection of photographs. And there were, always, protests to participate in; his next-to-last arrest was in 2002 at a Catholic Worker-organized protest at the U.N., his last in 2015, for blocking the U.S. Mission to the United Nations in a protest against nuclear arms organized by WRL, the Catholic Worker, Grannies for Peace and other groups.

Yet eventually, age took its toll. He attended fewer meetings, wrote less, and spent more energy working on the photo archive. Two weeks ago, he fell at home. On August 15, friends found him lying unconscious, his ailing cat Shaman sitting with him, and called an ambulance. Shaman died the next day. David survived one more day than that, without regaining consciousness. He died at Mt. Sinai-Beth Israel hospital early the morning of August 17.

…

On the announcement of his death, condolences poured in to WRL and the media—mass and social—buzzed with obituaries and reminiscences. The press and individuals alike spoke and wrote about his great work for, and commitment to, peace, nonviolent direct action, and socialism.

Among those who knew him, however, the reminiscences were more bittersweet, the loving and respectful tributes mixed with frank comments about his weak spots. A big man in every way, his virtues and weaknesses were almost equally outsize. Indeed, even before his death, those weaknesses were common knowledge and often the subject of discussion along those who knew him. In the issue of the Nonviolent Activist commemorating his career, a colleague wrote, “None of us always agreed with David; often enough, all of us disagreed with him.”

That was true, and it was also true that some of those disagreements were bitter—David expressed every opinion he had, with little concern for how it might be received. Disclaimer: I worked with David’s for almost 20 years; I’m a member of the community in which he lived and worked. In the days since he died, I’ve spoken with many of our mutual friends and colleagues. They spoke to me as they did in public, about his passionate commitment to the causes he worked for, but several also spoke—not for attribution—about his anger when challenged. More than one noted, also not for attribution, that as a white man, he was all but blind to white and male privilege.

But if his weak points were larger than life, so were his strengths, and in the end, it’s those that everyone remembers most vividly: his public commitments, yes, but also his private strengths. He was unfailingly generous and almost infinitely compassionate. Although an enthusiastic carnivore, he loved most non-human animals, especially cats, and most especially the Siamese cats who were serially his companions for decades. He would stop a car—or insist that one he wasn’t driving stop—for a stricken animal, any animal, on the side of the road. And a person, any person, in trouble or sorrow, was his friend, even if they had been bitter enemies a moment before.

In the end, as journalist and political analyst Ethan Young wrote in his Facebook tribute to David, “To the new generation, who never got a good dose of Dave, you lost out. We’ll try to make it up to you.”

David McReynolds, presente!

Judith Mahoney Pasternak is a long-time U.S. writer and journalist in the progressive media and an activist for feminism, peace, and Palestinian self-determination. She worked with David from 1995 to 2013, first as the editor of the Nonviolent Activist, the War Resisters League magazine, and then as a member of its board.

David’s photos, as archived with Ruth Benn, are at http://www.mcreynoldsphotos.org/.

August 27, 2018

Share