Left on Purpose: A Movie on Life & Death, Movements and Mayer

Somber tonight, coming home from the truly unusual and important new film Left on Purpose, directed by Justin Schein, which premiered at NYC DOC – the world’s largest festival of documentary cinema. The movie chronicles the life of an acquaintance, Mayer Vishner, whose behind-the-scenes work in the US peace movement was essential to groups such as the Resistance and the Yippies.

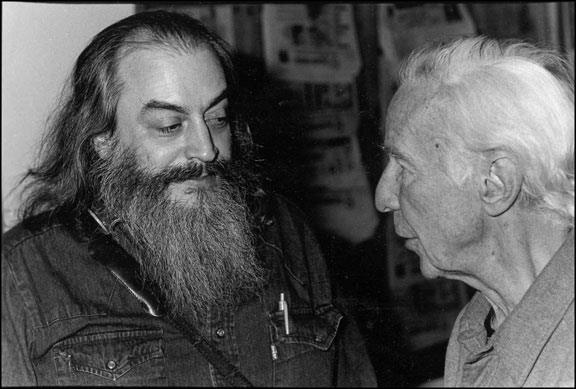

The subtle double-entendre of the title (Mayer’s contributions, as his exit, was very purposeful indeed) belies the subtlety of both the man and the movie. On casual glance – at least from the 1980s on, when I knew him – Mayer was part-humorist, part-curmudgeon, and part-sage; a cursory viewing of the film might also miss its deep and multiple meanings.

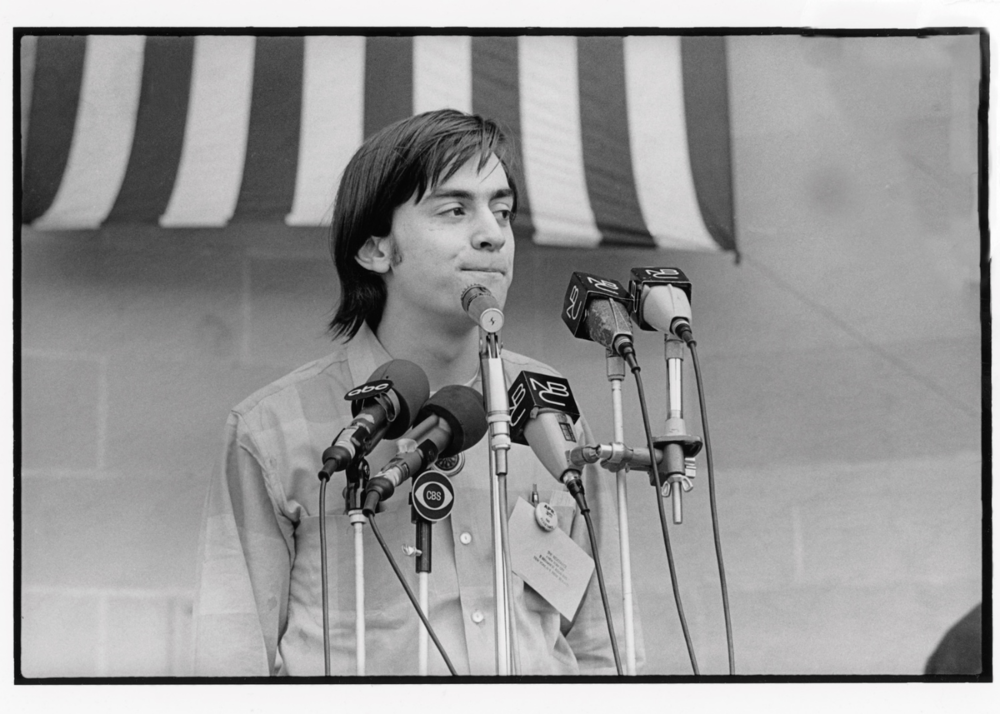

Upon careful inspection, one tends to agree with Mayer’s own assessment that he was more than simply a tag-along to some of the great historical figures of the latter half-century (Abbie Hoffman, John Lennon, Phil Ochs), but someone who helped maintain that greatness. One reference to Mayer’s relationship to Hoffman, the Yippies, and the most creative and politically pivotal protests of the late 1960s, was that Abbie was the media-brilliant magician, but Mayer was the teacher and scientist, the master-organizer who, though more than a decade younger, could help hold things together.

Left on Purpose may first appear an interesting review of an aging peacenik and a challenging commentary on the Heisenberg “observer” effect between filmmakers and their subjects, but in truth it is all that and so much more. Schein and company, for those who want to see it, have created a significant contribution to necessary conversations about contemporary US social movements, and the nature (and purpose) of life and death.

My connection to Mayer came early in my adulthood, through our mutual close relationship to the War Resisters League (WRL), which is not mentioned by name at any point in the film. Mayer was one of the younger members of the Vietnam-era draft resistance, and I was in the first round of early 1980s draft registration resisters, getting advice from Mayer and many others in the WRL orbit. When, in 1985, I was elected the youngest National Chair in WRL’s long history, Mayer and I discussed the irony of our times in the world; he sardonically considered himself a semi-outsider figure in the WRL, having unsuccessfully attempted no less than three times to get onto its administrative Executive Committee. But Mayer was a hanger-on, and he’d appear consistently at WRL events, and office parties, and (of course) protests, ever the stalwart anti-warrior. In the film, Mayer says some profound things about long-term radicals and the need to get out of the way of younger generations, but there is an ongoing conundrum here, made more poignant by the hindsight and reflectiveness which this film provides and sparks. How much do we of the left lose, being as negligent as we are at building the beloved communities we wish for but do little more than talk about?

One travels through the years which the movie covers looking for clues as to how a better ending might be arrived at. It is easy to say that having a positive attitude throughout one’s life is important, or that there are successful treatments for chronic depression or alcoholism; all that is true but perhaps not quite to the point. In the film’s first frames, we hear Mayer explaining the crucial but understandable error of so much of his generation: “We expected the revolution to come next Thursday.” The let-down and reaction to that mistake was handled widely differently by people of different standing in society, and with different characterological traits and ego-sizes. For Mayer, who never enjoyed major celebrity status even within the small confines of U.S. progressive circles, this let-down compounded personal conditions which were also tempered by his desire to let others take the lead. “I don’t speak the language anymore,” he says, despite clearly having an intense conversation with an Occupy activist and also despite the fact that we are living in a period when language is extremely transitory and inexact, with shifts and changes taking place all around us. “Filling me in slows people down,” Vishner noted.

The US left, always a reflection of society as a whole, has never been particularly good at empowering, honoring, or even simply utilizing the youth and the elders around us. As a key leader at one end of the spectrum during a time of unprecedented tumult and fervor, Vishner was left very much alone when he reached the other end – no revolution, little community, and fragmented movements which in no way knew how to engage his numerous skills. The irony of the documentary is that it now shines a spotlight on a man who in some ways truly wanted one, a man who found success if not happiness in sticking to his ideals. For the rest of us however, we’d do well to use a lesson from this perspective on Mayer, like one lesson of the “Sixties” and revolutionary struggle in general: to treat life, ourselves, and one another in more embracing, affirming, long-term, and loving ways.

By: Matt Meyer

Topics:

- Militarism

- |

- Nonviolence

- |

- Nonviolent Activist

- |

- War

- |

- WRL History

Resource Type:

- Statements and Commentaries