The Roots of Revolutionary Nonviolence in the United States are in the Black Community

By Joanne Sheehan

First published on Waging Nonviolence, February 15th 2021

Many are wondering how to respond to the current white supremacist threat. We only have to look to history — to those who organized against the brutal culture and laws of segregation in this country — for inspiration on the importance of relationship building, creative strategies and training to dismantle it today. Few people today know that it was transnational solidarity between Black and white Christian clergy in the United States and Indian activists fighting for independence from British colonial rule that introduced the philosophies and strategies of revolutionary nonviolence to the United States, and that this work would build the foundation leading towards the civil rights movement.

In the late 1930s, Black people around the United States were searching for leadership and methods to end racial discrimination. Black publications were reporting on the Indian liberation movement with great interest. Indians and others involved in the movement for Indian independence brought the story to the United States. And Black leaders traveled to India to meet with Gandhi, with growing interest in the method of satyagraha, which translated into “nonviolence.”

Among them was Howard Thurman, a distinguished African American theologian, educator and author, who met with Gandhi while on a religious speaking tour in India. Gandhi told Thurman that he regretted that nonviolence was not more visible worldwide and proclaimed, “It may be through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of nonviolence will be delivered to the world.”

Howard Thurman was a mentor and colleague of many civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., James Farmer, Pauli Murray, James Lawson and A.J. Muste, and would go on to inspire many more about the possibilities of nonviolence through his writings and teachings. Though many urged him to be their leader, his focus remained more on promoting the use of nonviolent strategy and practice. His work would be foundational for the civil rights movement decades later.

In 1940, two white ministers, Ralph Templin and Jay Holmes Smith, who had been kicked out of India for supporting the independence movement, established the Harlem Ashram. Based on Gandhian ashrams, residents were committed to simple living and daily spiritual reflection. The integrated community studied the Gandhian methods of nonviolence, exploring how it could be used to end racial discrimination in the United States.

While many of the early promoters of the use of nonviolence in the United States were Black and white Christian clergy, including Haynes Holmes, who went to London to meet Gandhi in the late 1930s. The Harlem Ashram became a gathering place for a broader group of Black people working for freedom and their allies: antiracist pacifists, many with ties to the War Resisters League and Fellowship of Reconciliation, or FOR, and who had spent time in India with the independence movement. While supporting Black leadership, this integrated group of women and men worked to develop an understanding of how satyagraha could be used to end state-sponsored segregation and discrimination. They worked primarily in the North and engaged in nonviolent direct actions to desegregate establishments in New York City.

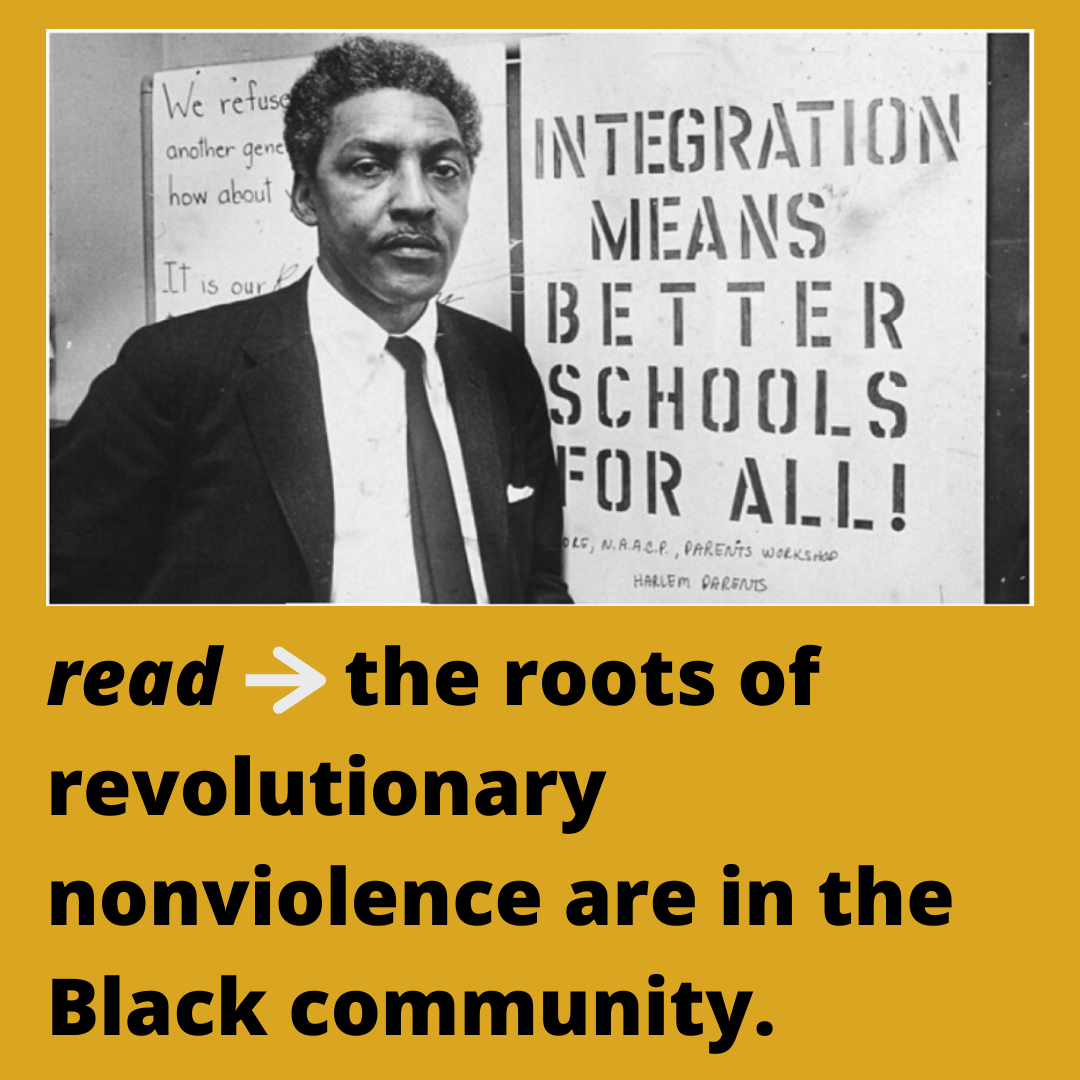

Bayard Rustin, a pacifist who was involved in racial justice work, lived nearby and was often at the ashram, as was A. Philip Randolph, the founder and president of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Together, these two worked on the 1941 March on Washington Movement and the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. By encouraging the use of nonviolence guidelines and facilitating training in the first month of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rustin helped create the foundation for nonviolent campaigns that followed.

Krishnalal Shridharani, who had been involved in several campaigns in the struggle for Indian independence, came to New York in 1934 to attend Columbia University, where he wrote his PhD thesis “War Without Violence: The Sociology of Gandhi’s Satyagraha.” Published in 1939, his book became a foundation for understanding the techniques of nonviolent action. Those who gathered at the Harlem Ashram, where Shridharani also lived for a while, used it to plan and prepare for nonviolent actions to dismantle segregation.

James Farmer, a co-founder of Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, in Chicago in 1942, lived at the ashram for a while. “War Without Violence,” with its analysis and outline of the nonviolent direct action being used in the Indian freedom movement, influenced the nonviolent strategy of CORE. Soon after CORE was founded, Farmer and white ally and co-founder Bernice Fisher, organized the first civil rights sit-in at a coffee shop in Chicago.

CORE was committed to providing nonviolent trainings. In 1947 CORE organized the Journey of Reconciliation, the first freedom rides. An interracial group of eight Black and eight white men rode on buses through the upper South to test the 1946 decision outlawing segregation on interstate travel. It was organized by Bayard Rustin and George Houser — a white activist with the War Resisters League and FOR — who co-facilitated the nonviolence training to prepare the group for their dangerous two week journey.

Many of the participants had met through civil rights activities during the ‘40s, and were World War II resisters. Members of this group went on to organize and train CORE’s DC Summer Workshops, including Bayard Rustin, Wally Nelson and George Houser. Wally and Juanita Nelson and Ernest and Marion Bromley, along with Ralph Templin — and many who had been involved in the Harlem Ashram and CORE — founded the Peacemakers in 1948, and organized the present-day war tax resistance movement.

Pauli Murray, who was involved in the civil rights and gender equality movements — calling sexism “Jane Crow” — lived at the ashram for just a short period of time, but continued her work with many she met in that community for decades. Pauli Murray and Ella Baker, had both been organizers for the Journey of Reconciliation in 1947 and wanted to be participants, but the men thought that would be too dangerous. While in law school at Howard University, she defended student activists, including Juanita Morrow (Nelson), who participated in a sit-in at a D.C. luncheonette in the early ‘40s.

While it only lasted from 1940 to 1948, the multiracial community created to explore ways of using nonviolent action against racial injustice was influential in doing that. Through the relationships that were made, as a space to gather and engage in strategic discussions and develop nonviolence training — and where an integrated community fostered Black leadership — it was an incubator for the civil rights movement and strategic revolutionary nonviolence.

While World War II slowed down the process of nonviolent action for racial justice, many of the Black and white war resisters continued their work in prison. And a younger group of Black leaders were about to emerge, strengthening and broadening the movement.

By the time Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a segregated Montgomery bus in 1955, there already was a rich tradition of nonviolent direct actions against segregation. Parks was an active member of the NAACP who had recently attended Citizenship Training at Highlander Center led by Septima Clark.

Martin Luther King Jr. was not only chosen to lead the Montgomery Improvement Association, established to coordinate the bus boycott, because he was the young new pastor in town. He had thought deeply about nonviolent action, inspired by Howard Thurman and by his wife Coretta Scott, who had been committed to nonviolence since she was a student at Antioch. War Resisters League sent Bayard Rustin and FOR sent Glenn Smiley to Montgomery with resources to support the nonviolent campaign.

In 1957 Black leaders in the growing movement gathered to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or SCLC. With an aim of spreading the nonviolent methods used in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the founders (including Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy of Montgomery, Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham, Bayard Rustin and Ella Baker) adopted nonviolent mass action as the cornerstone of strategy.

When Highlander Center could no longer meet the need for citizenship trainings, Dorothy Cotton of SCLC took over the coordination. These workshops made a real difference in strengthening the movement, with over 6,000 participating in classes on voter registration, and personal and community empowerment.

James Lawson, a conscientious objector, spent a year in prison for refusing to register for the draft and three years studying and teaching as a Methodist missionary in India. Learning about the Indian movement’s successful efforts for independence strengthened his belief in nonviolence as an instrument for social change. He returned home in 1956 as the Montgomery Bus Boycott was using those methods. He had also read Howard Thurman’s “Jesus and the Disinherited,” and wanted to be involved. With the encouragement of Martin Luther King, Jr, and through A.J. Muste and Glenn Smiley of FOR, Lawson was encouraged to go to Nashville.

There Lawson began workshops in nonviolence with students at the two Black colleges and a few white student allies. This story is well documented in the segment on Nashville in “A Force More Powerful” and David Halberstam’s “The Children.” Beginning in September of 1959, the workshops drew increasingly large numbers of students, and violence from the white establishment. While they were preparing for a lunch counter sit-in, they heard of the four students in Greensboro who sat down at a Woolworth’s lunch counter and asked to be served on February 1, 1960. On February 13, 124 young people, nearly all of them Black, armed with nonviolent discipline and strategy, walked from the Nashville church that was their gathering site to the segregated lunch counter downtown. Thanks to the months of training, the leaders of this campaign became the young leaders of the movement.

With the inspiration of Greensboro and Nashville, young people around the country were holding sit-ins at segregated lunch counters and doing solidarity actions at chains such as Woolworth’s. A conference was to be held in April, organized by Ella Baker at SCLC, who was critical of the top down leadership at the organization. She wanted students to be invited, including Diane Nash, John Lewis, Marion Barry, Bernard Lafayette, and James Bevel from the Nashville campaign. Stokely Carmichael from Howard University and Julian Bond from Morehouse College were among the 126 student delegates who attended from over 50 sit-in efforts. They created the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, as an autonomous organization committed to nonhierarchical participatory democracy with a commitment to consensus decision making. A new generation of young Black leaders became the nonviolent strategists, organizers and trainers for SNCC.

In addition to supporting the lunch counter sit-ins, they helped organize the 1961 Freedom Rides, voter registration campaigns in 1962, and the 1963 March on Washington with many other civil rights organizations.

It is important that we understand and appreciate the key roles Black people, of all ages and genders, played in introducing and developing revolutionary nonviolence in the Western world. The myths that it was the work of a few well-known African Americans who are celebrated this month, including the “tired seamstress” and Martin Luther King, need to be corrected. The narrative that nonviolence is not power but passivity demanded of Black people, must also be challenged. And to honor their legacy, we need to commit to exploring how the power of revolutionary nonviolence can be effective in continuing the struggle for justice.

This story was produced by War Resisters

Joanne Sheehan

Joanne Sheehan is a nonviolent direct action trainer and co-founder of WRL New England.

Share