From Bases to Bars

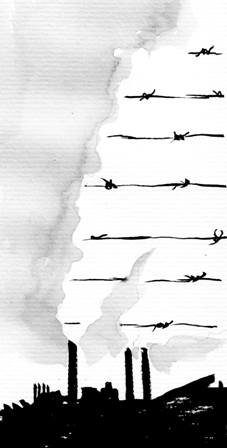

The Military & Prison Industrial Complexes Go ‘Boom’

Looking back to the halcyon days of the movement against the Vietnam War, one sees the birth of what seemed to be a new world. Every day, one could almost see and touch giant boulders crumbling off the edifice of repression: students protesting from coast to coast—even as some students at Kent State (Ohio) and Jackson State (Mississippi) Universities were being shot to death by National Guardsmen and police, for demonstrating!—a president resigning in disgrace; soldiers returning from war join the protests, many in their battle fatigues.

Few could have envisioned a future some two generations hence, when the nation would not only be involved in two wars simultaneously (also begun under false, misleading pretexts) but would rival Rome in its bases in virtually every region of the world, a vast, armed archipelago of empire erected by the permanent government—the corporate government, on behalf of corporate interests.

As Chalmers Johnson, author of Nemesis, has observed, the post-Vietnam military resolved to erect a system immune from the popular and democratic will that spelled the end to that war. In part, they did this by abolishing the draft. Johnson explains:

It takes a lot of people to garrison the globe. Service in our armed forces is no longer a short-term obligation of citizenship, as it was back in 1953 when I served in the navy. Since 1993, it has been a career choice, one often made by citizens trying to escape from the poverty and racism that afflict our society. That is why African-Americans are twice as well represented in the army as they are in our population, even though the numbers have been falling as the war in Iraq worsens, and why 50 percent of the women in the armed forces are minorities. That is why the young people in our colleges and universities today remain, by and large, indifferent to America’s wars and covert operations: without the draft, such events do not affect them personally and therefore need not distract them from their studies and civilian pursuits.

Johnson, writing of the United States’ “increasingly powerful military legions,” states that over 700 U.S. military bases cover the world, acquired through threat, subterfuge, sleight of hand, or questionable payment of host states.

These hundreds of bases, regardless of how they were acquired or are retained, constitute an imperial presence abroad and a none-too-subtle check on a “host” nation’s political (and military) options.

In Bushian parlance, the presence of these bases is the essence of “force projection”—the ability of the U.S. imperial military to project its forces around the globe at whim.

Even Rome would envy such a capability.

Was force projection not the essence of the (latest) Iraq war? While a United States traumatized by the events of September 11 was force-fed fears of weapons of mass destruction (via a supine media and a compliant Congress), U.S. military thinkers knew better.

Chalmers Johnson cites retired Air Force Colonel Karen Kwiatkowski, a former strategist in the Near East division of the Secretary of Defense. When asked, “What are the real reasons for invasion of Iraq?” she responded:

One reason has to do with enhancing our military-basing posture in the region. We had been very dissatisfied with our relations with Saudi Arabia, particularly the restrictions on our basing. … So we were looking for alternate strategic locations beyond Kuwait, beyond Qatar, to secure something we had been searching for since the days of Carter—to secure the energy lines to the region. Bases in Iraq, then, were very important.

The unstated question, “Why?” is answered by the obvious. As long ago as 1945, the U.S. State Department was eying the Persian Gulf region with something akin to lust.

U.S. anti-imperialist critic, author, and linguist Noam Chomsky noted in his 2007 work Interventions that the events of September 11 opened wide the door to a long-coveted “prize”:

The September 11 atrocities also provided an opportunity and pretext to implement long-standing plans to take control of Iraq’s immense oil wealth, a central component of the Persian Gulf resources that the State Department, in 1945, described as a “stupendous source of strategic power, and one of the greatest material prizes in world history.”

This prize is at the very core of why the current Iraq War is being waged and why almost all wars are fought: for resources. For wealth. For power.

Fighting terror, fighting crime

Perhaps it is not too surprising to find a similar trajectory, from big to bloated, from massive to vast, in the prison industrial complex (PIC) as in the military industrial complex (MIC). The similarity is not coincidence. They are two sides of the same coin.

Linda Evans, a former anti-imperialist political prisoner, and Eve Goldberg, a prison activist, have penned a pamphlet, The Prison Industrial Complex and the Global Economy, that conclusively shows not just the correlation between the MIC and the PIC but the interrelationship with the emerging global economy. They write:

Like the military/industrial complex, the prison industrial complex is an interweaving of private business and government interests. Its twofold purpose is profit and social control. Its public rationale is the fight against crime.

Not so long ago, communism was “the enemy” and communists were demonized as a way of justifying gargantuan military expenditures. Now, fear of crime and the demonization of criminals serve a similar ideological purpose: to justify the use of tax dollars for the repression and incarceration of a growing percentage of our population. … Most of the “criminals” we lock up are poor people who commit nonviolent crimes out of economic need. Violence occurs in less than 14 percent of all reported crime, and injuries occur in just 3 percent. In California, the top three charges for those entering prison are: possession of a controlled substance, possession of a controlled substance for sale, and robbery. Violent crimes like murder, rape, manslaughter, and kidnapping don’t even make the top ten.

Remember the Reagan administration’s “war on drugs”? It has led to the largest prison binge on earth, and if it were indeed a war rather than a poor metaphor, then the massacres erupting from Mexico would signal the Tet Offensive that spelled the end of the Vietnam War. The only thing missing from the war on drugs is a signature on a piece of paper pleading surrender.

Whole communities have been shattered, and where once hundreds of thousands were cast into U.S. dungeons, prisons now hold millions, with millions more under lifetime voting bans and career blockages—in virtual prison while ostensibly free.

Just as cynicism led to wars abroad, similar social forces waged war on Americans, as, in many states and jurisdictions, the only growth industry could be found in construction, jobs, and services in the PIC.

How much has it grown?

The United States, the abode of some 6 percent of the world’s population, today imprisons nearly 25 percent of all the prisoners on earth.

In her book Is the Prison Obsolete? scholar-activist and prison abolitionist Dr. Angela Y. Davis, herself a political prisoner during the Black Liberation movement of the 1960s, brings her unique lived and learned perspective to the question:

When I became involved in antiprison activism during the late 1960s, I was astounded to learn that there were then close to two hundred thousand people in prison. Had anyone told me that in three decades ten times as many people would be locked away in cages, I would have been absolutely incredulous. I imagine that I would have responded something like this: “As racist and undemocratic as this country may be [remember, during that period the demands of the Civil Rights movement had not yet been consolidated], I do not believe that the U.S. government will be able to lock up so many people without producing powerful public resistance. No, this will never happen, not unless this country plunges into fascism.”

Captive Markets

Along with the immense and unprecedented explosion in the U.S. prison population has come the expansion in business for corporations trading behind bars.

Prisons today, although islands separated by brick and steel from “free” society, are captive markets where billions are made by merchants.

From Dial soap to Famous Amos cookies, there’s enormous profit to be made. In 1995 alone, Dial sold more than $100,000 worth of its products to the New York City jail system. VitaPro Foods, a Montreal-based maker of soybean meat-substitutes, sold $34 million worth of its products to Texas state prisons.

Names of corporations that sell their stocks on the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq, such as Archer Daniel Midlands, Nestle Foods, Ace Hardware, and Polaroid, are also found as business advertisers on corrections.com.

The PIC is a field in which remarkable profits are harvested.

Aftermath

The MIC has created not security but the very absence of it. The lack of safety was exacerbated by the excesses of the George W. Bush administration, which promoted a foreign policy best summed up as “Operation Imperial Arrogance.”

The Iraq War, prosecuted with an intensity that was to be expected under the billing of “shock and awe,” delivered unprecedented death and destruction to the country, but the resistance, which took months (and U.S. provocations) to mobilize, delivered such a drubbing to U.S. forces that the strategic and political leadership had to unwrap new ways of working in the Iraqi field.

The aftermath of this once-impressive military exercise, now undercut by several years of urban guerrilla counterattacks, left some of the United States’ allies in the region underwhelmed, if not somewhat contemptuous of U.S. political elites.

The PIC, driven more by malevolent market forces than strict legal necessities, affected the nation in more ways than the obvious. In the fall of 2004, some 5.3 million people were considered disenfranchised felons, meaning they were unable to vote. Many of them, if they had voted, presumably could’ve changed the fate of the country by preventing the election of George W. Bush and, theoretically at least, prevented the Iraq War from some of its strategic and tactical errors. It is possible that their votes could’ve contributed to an earlier cessation of the war.

Indeed, if several thousand had been allowed to vote in Florida in 2000, perhaps both wars could’ve been avoided. This is speculative, however, given the corporate control over both parties and the propensity of both parties to advance similar objectives, albeit with differing rhetoric.