BOOK REVIEW: To Everything There Is a Season

Singing Solo, But Not Alone

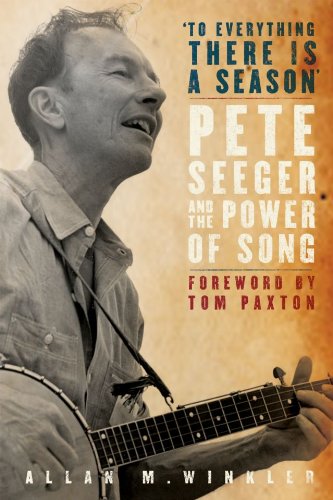

‘To Everything There Is a Season’:

‘To Everything There Is a Season’:

Pete Seeger and the Power of Song

By Allan M. Winkler

Oxford University Press, 2009, 256 pages, $23.95

From a gangly 20-year-old to a still-skinny nonagenarian, Pete Seeger has always been a phenomenon. Allan Winkler’s detailed yet accessible book places Seeger’s long life and work in its historical context. It should make a new generation aware of the struggles of the last century and Seeger’s role in them. On the other hand, it suffers from an unfulfilled promise: The methods by which “the power of song” is achieved are merely alluded to, not demonstrated.

To Everything There Is a Season is organized chronologically, with chapter headings selected from songs associated with various stages of Seeger’s career. After a prologue, which deals with Seeger’s parents and his upbringing, the chapters range from “If I Had a Hammer” (The Weavers and the Cold War) to “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” (the anti-Vietnam War movement) and beyond.

Most of the important moments in Seeger’s career are covered, briefly but with clarity. For example, the book describes his important musical influences, especially Leadbelly and Woody Guthrie, both of whom are introduced to the reader (and to Seeger, by folklorist Alan Lomax) early in the book. The book benefits from the inclusion of many photographs, largely from Seeger’s and his wife Toshi’s personal collection. They include everything from the singer at a union hall and at a school auditorium to Seeger sitting next to Henry Wallace and shaking hands with Bill Clinton.

The book is of great value in helping us, especially younger readers, who haven’t experienced the times themselves, grasp the social/political context in which Seeger has worked. It is also enlightening in describing his creative process—how he synthesizes different strands of folk and other material into a new whole. Another strength is in the description of his almost magical ability to draw an audience in: to sing, clap in rhythm, and improvise harmonies. This aspect of his performance style is central to his view of the role of song. He wants his audience to “own” a song. A passive audience is anathema to Seeger. He wants an active one; activity can become activism.

The book is weaker when it comes to developing the approach suggested by the subtitle. Many of the songs’ texts are merely quoted, with little more than an adjective or two of description. Here, for example, is part of Winkler’s presentation of “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”:

The song was simple, lyrical and repetitive. As the United States found itself confronting the Soviet Union and Seeger faced a confrontation of his own with anti-Communists, the song had an unmistakable political message. It began simply:

[The song’s original three verses are then quoted verbatim.]

The song was an intensely personal plea to help create a more peaceful world. It conveyed a sense of sadness at the military struggles that killed the young, and it was particularly poignant at the height of the Cold War, when quiet conflict threatened to develop into devastating war. It reflected the values that had guided Seeger all his life and underscored the need for accommodation rather than armed clash.

But there is no close reading of either the song’s text or its music. Absent is any discussion of the role of the interpolated “long time passing” or whether the perennial complaint adds to or detracts from the song’s power or how. An analysis of the melody shows that each statement of the persistent question (“Where have all the flowers gone?”) shares the same music: the question won’t go away! Each questioning statement is interrupted by the contrasting music of the interpolation (“long time passing…long time ago”). The answer (“The girls have picked them, every one”) links the two: it is in the higher range of the interpolation, but its melodic shape is that of the question. Finally, the complaint is different musically from everything preceding it. Thus, disparate materials are woven together to make a coherent whole, with the focus on the persistent question and its answer, enriched by the comments.

This reviewer was also disappointed by the accompanying CD. There is only one song—“Wimoweh”—in which there is any interaction between him and an audience. Moreover, for all of his many years of participation with the Almanac Singers and with The Weavers (both well covered in the book itself), neither group is included on the CD. Every song features Seeger as a solo artist. This falsifies the message of the book itself, which takes pains to emphasize his dedication to cooperativeness, his stress on audience participation, and his loyalty to the anonymity of the folk process.

I would have liked to see two songs included: On the CD of The Weavers’ 1963 reunion concert at Carnegie Hall, Lee Hays sings the first verse of “If I Had a Hammer,” Ronnie Gilbert sings the second, Seeger sings the third, and all The Weavers join in on the final verse. This version includes the original text (“all of my brothers”) and presents The Weavers in action, with their rich vocal harmonies and excellent ensemble work. The other would be the version of “We Shall Overcome” recorded at Seeger’s Carnegie Hall performance in the late 1960s. He introduces the song by saying, essentially, “You don’t need to go south to participate in these struggles against segregation; you can donate money or your time in support work.” He then begins the song, and almost immediately the huge audience joins in, with Seeger improvising harmony and counterpoint above and around it. This is a concrete demonstration of the “power of song.”