The End of Public Education

And the New American Revolution

Though we may not like to admit it, the U.S. commitment to publicly supported teachers and students is coming to an abrupt end. The global corporate penchant for privatization, commoditization, and enclosure is having chilling effects on policies that scholar Henry Giroux suggests “seek nothing less than the total destruction of the democratic potential of American education.”

Under the Clinton administration, education was remolded to suit an economic system that could just as easily use “labor market boards” as institutions of learning and empowerment. Now, right-wing pundits are calling for a complete dissolution of the Department of Education while billionaires pump funds into local and state education systems to all but ensure that they become privately controlled centers that will better sort workers for 21st-century business needs.

This global phenomenon, part of the neoliberal agenda whereby most workers do not need much traditional academic information, sees highly educated, lifelong “professional” teachers as a central problem for smooth-running, globalized economies. By raising student expectations and civic involvement and demanding higher wages and better working conditions, they cost more than they are worth. Throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the World Bank and other free-market institutions have implemented large-scale privatization campaigns with their necessary attack on unionism, disenfranchisement of parents and communities, and de-intellectualizing of schools.

It Has Happened Here: Education, the Military, and Prisons

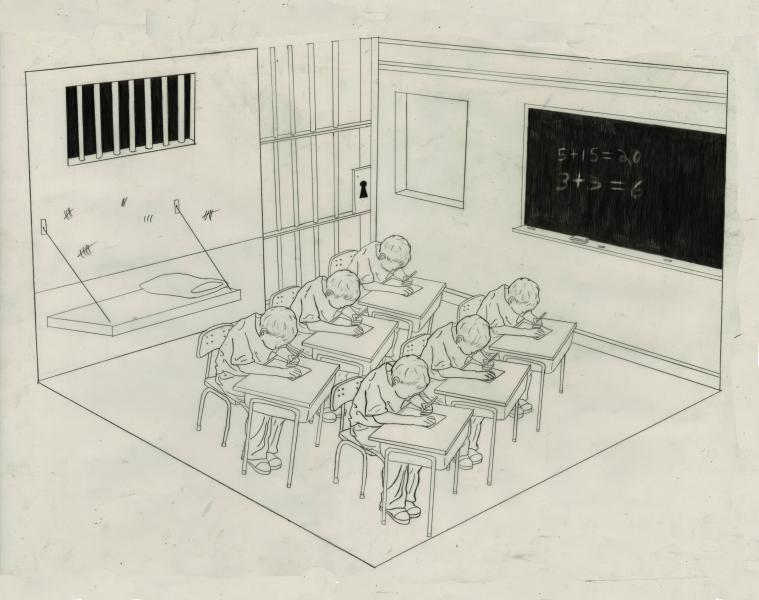

The same political analysis that views school as a space for marketplace training has also been crucial to the movement for zero-tolerance discipline and high-stakes testing. Imposing punitive, militarized solutions to crisis created by chaotic, community-based social ills (poverty, unemployment, the housing shortage, and the resulting traumatic home lives), middle and high schools have become an early introduction to prejudicial policing and the “positive” alternatives that a life in the U.S. Armed Forces can offer.

Beyond the obvious links between war spending in the midst of a failing economy that calls for teacher layoffs and cuts in services, there is the more pernicious problem of a curriculum based on military mythology. Military recruitment in U.S. secondary schools was on the rise throughout the 1980s and ’90s, but the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 gave the military unprecedented access to young people in and out of school. Certain groups, like the New York Collective of Radical Educators (NYCORE) and San Diego’s project on Youth and Non-Military Opportunities (YANO), have worked hard to reverse this trend. But with an over-burdened peace movement that makes only occasional links to unions and parent groups, these initiatives remain largely camouflaged. The basic tenets of No Child Left Behind—a national curriculum, high-stakes testing, and the militarization of schools in poor and working-class communities—have only been invigorated by President Obama’s Race to the Top initiative.

For those who cannot conform to the new rules of a cookie-cutter curriculum and who do not opt for the military “alternative” to factory-based education or burger-flipping underemployment, there is one ever-increasing opportunity that will still provide subsidized housing and gainful work: going to prison! The statistics about young men of African descent (jailed at a rate far above that of South Africa during apartheid and the radical resistance to that racist regime) are just the tip of the prison iceberg. Mainstream, liberal civil rights groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Urban League, and others have called the contemporary crisis for education of children of color a “state of emergency.” There has been less attention paid, in these desperate fiscal times, to the 660 percent growth rate of the prison industry in the last two decades.

The National Center for Fair and Open Testing, one of the most widely respected research-based associations of progressive educators, has documented how the standardized testing craze has helped fuel the school-to-prison pipeline. The fact that some states have even planned future budget allocations for building new prisons based on the number of failing math and English language test scores among third graders is just one grotesque example of this trend. Civil rights advocate and legal scholar Michelle Alexander, calling the current process of imprisonment in America “the new Jim Crow,” reminds us that the connections among race, class, education, militarization, and repression are deepening.

The Capitalist Manifesto

In October 2010, a collection of 16 superintendents from some of the largest school districts in the country came together to write a “manifesto” entitled “How to Fix Our Schools.” In conjunction with the quasi-documentary Waiting for Superman (much of the footage was staged), this manifesto laid the failure of U.S. education at the doorstep of tired and incompetent teachers, who apparently make up much of the educational workforce. Their evil benefactors and backers, the local and national teacher unions, are the main target of the campaign to “fix” problems which social science research suggests are entrenched throughout the whole of our socio-economic system. Economic Policy Institute associate Richard Rothstein reminds us that decades of studies have corroborated that all in-school factors (of which the quality of teachers is just one component) make up just one-third of the reasons why some students succeed while others fail. The other two-thirds of the causes of the achievement gap have little to do with anything that goes on inside schools, relating instead to the more intractable issues of poverty, racial discrimination, and other requirements of capitalism.

Many of the superintendents associated with the manifesto were “made redundant.” Michelle Rhee of Washington, D.C., lost her position when the mayor who backed her was voted out of office. Superintendent Ron Huberman of Chicago resigned, and Philadelphia’s Arlene Ackerman claimed to have been falsely listed as a signer, noting that getting rid of teacher’s unions or rights, including tenure, would not end school failure—especially at a time when schools are expected to solve “many of the ills [of] the larger society.”

The funders of this capitalist manifesto, like the promoters of standardized tests, are still very much in place. These funders—from Bill Gates to Eli Broad and Michael Bloomberg—can shield themselves from bad press because they can buy their own press. They can distance themselves from politicians when policies go sour, for they have nothing to lose but their claims. But they will still have the attention and the allegiance of the president and his secretary of education.

Former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich has suggested that “a perfect storm” of economic and social factors are gutting democracy and creating a “plutocratic” capitalism. The fall 2010 issue of the National Education Association’s news magazine reported that a New Jersey teacher of the year was just one of the victims of layoffs that affected 80 percent of the nation’s school districts. Respected former New York City Deputy Chancellor Carmen Farina notes that the policies of the new manifesto reformers feel like they’re aimed not at strengthening learning but “eliminating public schools.”

At the 2010 U.S. Social Forum People’s Movement Assembly focusing on education, Vincent Harding, a theologian and adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., presented on the educational requirements of a multiracial, democratic society. He noted that—for those who look to a future of peace—“we are citizens of a society which does not exist yet.” South African poet Dennis Brutus used to remind us that “revolution always seems impossible for a long, long time … until things speed up all at once, and then it seems inevitable.” For a generation who felt certain that apartheid couldn’t end without a bloodbath and who believed that we’d never live to see a U.S. president of African descent, we must open our imaginations widely to plan for renewed struggle.

Public schooling, after all, is not worth fighting for if it is merely a minor reform aiding the maintenance of an unjust status quo. But if the classrooms we create are centers for critical change, for empowerment and liberation, for peace with justice, then the fight we’ll be part of is for nothing less than a livable future.

Read an expanded version of this article at New Clear Vision.