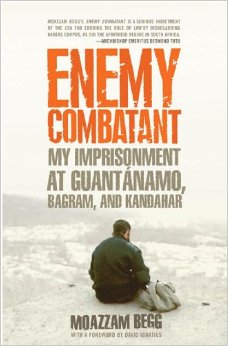

Enemy Combatant

Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at

Guantánamo, Bagram and Kandahar

by Moazaam Begg

The New Press, 2006

397 pages. $26.95, hardcover

Everyone who is concerned about human rights, indefinite imprisonment, the U.S. policy of torture at off-shore prisons, and the now defunct right to a writ of habeas corpus, will want to read this book.

Inside Enemy Combatant, Moazaam Begg, a British Muslim who was held for two years in Afghanistan and Guantánamo Bay, gives a disturbing account of how the United States is violating the human dignity of large numbers of people it deems “enemy combatants.” Despite being kidnapped, and subjected to torture throughout his imprisonment, Begg maintains an attitude of compassion for those around him — a remarkable feat in the face of revenge and vindictiveness that is a widely accepted response to violence.

Begg grew up in Birmingham, England where his father, an immigrant from Pakistan, was a banker and provided him an excellent education at a Hebrew school. As a young adult, Begg was conscious of discrimination against Muslims both through his own experiences and the knowledge that those killed, raped, and losing their homes in the conflicts in Bosnia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and Palestine were all Muslim.

His initial response to help impoverished Muslims struggling to live under war was to send money. But he knew that that wasn’t enough. He traveled with the Convoy of Mercy delivering aid to Bosnia, but knew that wasn’t enough. He thought, “How can I sit quietly in an office all day after what I have seen?” Begg then started to learn Arabic and opened a bookstore in Britain with a friend, where Islamic books, clothing and artifacts were sold and where study groups were held.

Begg and his wife, Zaynab, wanted their children to experience life in a Muslim country and decided to live in Pakistan for five months. He also began working — building water wells and a school for girls — in Afghanistan, where he and his family relocated in 2001.

On October 17, 2001, a U.S. cruise missile landed so close to their home that shock waves broke their windows. Begg arranged to get his family and two others to a compound near the Pakistan border. He drove back and forth from the compound to Kabul to get food and news. One day he could not return as the fighting intensified, roads were blocked, and it wasn’t safe to travel. In an agony of worry about his family, he joined a group of people who walked through the snow-covered mountains toward the border. It was three weeks before he and Zaynab found each other. With help from their families, they set up a home in Pakistan and planned to help refugees from Afghanistan.

On the evening of January 31, 2002, the children and Zaynab were asleep and Begg was at the computer writing a letter. The doorbell rang and American and Pakistani men entered and put a gun to Begg’s head. They put him in a hood and cuffs and carried him into a vehicle. The Pakistanis later told him that he was being held to appease the Americans, so that Pakistan would not be attacked by Bush’s army.

Held in what seemed to be an intelligence service facility, not allowed to contact family or call lawyers, Begg saw prisoners tortured: hit with pipes, subjected to sleep deprivation, and beaten. During his detention, he witnessed the murder of two prisoners. Begg realized that the truth didn’t matter to the guards; prisoners were tortured until they said exactly what the torturers wanted to hear.

After what seemed to be a few weeks, Begg was handed over to the U.S. military and transported to Kandahar in shackles, unable to breathe from the hood over his head. Chained in a cold cell while he listened to the screams of other prisoners, he suffered in Kandahar for months. “The most humiliating thing was witnessing the abuse of others and knowing how utterly dishonored they felt,” he writes. Throughout Begg’s detention he was interrogated often, day and night. Interrogators asked him the same questions over and over: every detail of his life, travels, friends. They wanted him to admit to events that he wasn’t involved in: training, financing, and planning Al-Qaeda operations.

Begg was then moved to the Bagram Air Base detention facility in Afghanistan. The routine of being shaved, beaten and hogtied and the dread of the hood, darkness, stress positions, and sleep deprivation continued. He would tell his interrogators: “All of you know that I haven’t committed any crime, nor have I been involved in one. I have done nothing to harm any American at all, and you’ve shattered the lives of my family and me for nothing.”

In January 2003, Begg was moved to the U.S. base in Guantánamo. At this point he had been isolated from other prisoners for two years. He was told he would never see his family again and that he could be executed by a firing squad at any time. Under these threates and with continued humiliating treatment, he signed a confession written by the FBI. Begg felt as though he had signed his life away.

At Guantánamo, Begg befriended many guards assigned to him and was often able to relate to particular soldiers who felt marginalized themselves. Becuse he was able to speak English, Arabic, and Urdu, and because he was willing to listen to people, Begg translated for the Red Cross and the guards and helped prisoners negotiate for their needs. Soldiers Begg spoke with expressed their opposition to this new war being waged, “a war that they believed overstepped the boundaries of what they had been taught was permissible. A few admitted to feelings of guilt and remorse at what they called a black page in the history of the U.S.A.”

Voice of Reason

Enemy Combatant was written after Moazzam Begg’s release from Guantánamo and return to England with is wife and children in January 2005. Despite everything he endured, Begg writes his story not with revenge and hatred in his heart, but “to find some common ground between people on opposing sides of this new war, to introduce the voice of reason, which is so frequently drowned by the roar of hatred and intolerance.”

This book needs to be read; prisoners need to be released. We, as people living in this empire, need to resist. The solution isn’t revenge or hatred; the solution is understanding and respect for all people and nonviolent resistance. Some often wonder how the people of Germany allowed the creation of Nazi concentration camps, but torture camps like Guantánamo are our concentration camps. No one who reads this book can say they didn’t know.