G.I. Joe: Lessons for the Coffeehouse Movement

During the Vietnam War, the 20 or so G.I. projects, which operated outside every important Army and Marine base, played an essential role in fomenting antiwar opposition among rank-and-file soldiers. This movement, along with the heroic resistance of the Vietnamese, arguably forced the United States to withdraw from Vietnam. As the recent military invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq soured, it became obvious that U.S. troops were going to be deployed in those countries for years to come. Drawing on our Vietnam War experience, Citizen Soldier decided to look into reviving a G.I. coffeehouse movement to oppose the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

After considering several East Coast bases, we decided to launch our new project near Ft. Drum in upstate New York. We chose this base because it’s the home of the 10th Mountain (Light) Division, which endures the highest deployment rate of any division in the U.S. Army. We rented a 1,500-square-foot space in a downtown shopping arcade in Watertown, N.Y., where we opened the doors of our Different Drummer Internet Cafe in October 2007. We immediately set out to spread the word about activities and counseling services we were featuring at the Drummer. We went online with our website to provide regular updates on cafe events. We also hooked up three computers, which passersby were invited to use free of charge.

Due to Watertown’s heavy reliance on Ft. Drum as an economic engine, we feared being blacked out by local media. These fears proved unfounded as both the local daily newspaper and the base paper were happy to accept our advertisements. The local TV news shows (as well as the New York Times and the Syracuse Journal Standard) reported on issues or soldiers’ cases that we publicized at our cafe.

Many G.I. projects during the Vietnam War attracted civilian volunteers who would commit six months or a year to living in the base town and throwing themselves into the work with soldiers. While we were able to recruit a few local volunteers, we had no luck drawing in fulltime help.

In addition to weekend dances for which we hired popular local rock bands to perform, we also scheduled a series of Saturday afternoon film screenings, followed by public discussion. While the documentary films we featured such as Sir! No Sir!, Iraq for Sale, and Body of War were exciting, the turnout for these events was not. We were lucky if one or two soldiers turned up for a film. Attempts to draw the few G.I.s out on the issues raised by the films mostly fell flat, with local peace activists dominating the discussion.

The small Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) chapter at Ft. Drum attempted to hold regular membership meetings at the cafe, but they were sporadic and poorly attended. We encouraged the national IVAW leaders to commit organizing resources to Ft. Drum, but aside from a couple of “bus tour” visits there was no sustained outreach. Some individual IVAW members tried to recruit among their units. However, the economic downturn has bolstered the Army’s success at winning re-enlistments. It’s likely that soldiers who decided to stay in felt that becoming a member of IVAW wasn’t a wise career move. There was also a problem with continuity of leadership because IVAW members who were discharged from the base couldn’t wait to leave the area.

We did register a few successes, such as co-sponsoring a picnic in a Watertown park in June 2007, which welcomed an IVAW bus that was touring military bases. Another success was turning the cafe into a gallery to display Nina Berman’s award-winning photography of wounded veterans, Purple Hearts. This attracted some soldiers and their families as well as sympathetic citizens and media attention. The show was later transferred to the commissary at Ft. Drum, where it hung for a few hours before an Army officer spotted it and had it taken down.

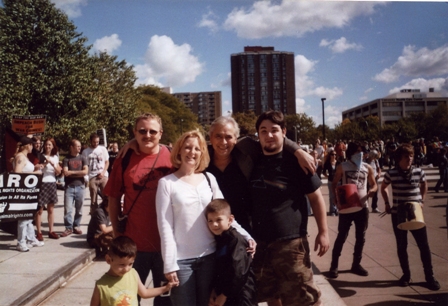

For me, an unavoidable truth presented itself when we organized our Ft. Drum Spring Festival to mark Armed Forces Day in May 2009. This event was organized in concert with several peace coalitions in Syracuse, Ithaca, Rochester, and Buffalo. About 100 demonstrators marched north to rally outside Ft. Drum to express opposition to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and to endorse health care for returning veterans. Advance press coverage by local TV stations and newspapers (including the New York Times) was extensive. We hired popular local rock bands, which we publicized with thousands of leaflets and large ads in both the local and base newspapers. That day, the Drummer rocked with music, speeches, and a strong political vibe. Yet, despite our best efforts, we had to acknowledge that we’d attracted almost no new soldiers or family members from the base.

Two months before the Different Drummer closed, the G.I. Voice, an organization of vets and peace activists, opened Coffee Strong, a new G.I. coffeehouse just outside Ft. Lewis, near Seattle, Wash. Seattle’s large progressive, antiwar community is an important source of staff and funding for the project. In addition to quality coffee, computers, and free wi-fi , the cafe offers concerts, political events, movie nights, and G.I. rights counseling. It also serves as a meeting place for groups such as IVAW and Veterans for Peace. Coffee Strong hopes to organize soldiers around post-deployment mental trauma, ending Stop Loss (involuntary extension of enlistment contracts), sexual assault and mistreatment of female soldiers, and support for resistance to deployment.

More recently, a new G.I. project, Under the Hood, opened in Killeen, Texas, adjacent to Ft. Hood, which is the largest Army base in the United States. About 59,000 soldiers and another 90,000 family members reside on or near the base. This project also benefits from its relative proximity to Austin, 60 miles north. This community is an important source of funding, volunteers, and staff for Under the Hood.

One Ft. Hood soldier, SPC Victor Agosto, who has been active with the project, announced in May that he would refuse orders to deploy to Afghanistan. “I have frequented Under the Hood since it opened in March,” he wrote on the cafe’s website. “The cafe has become my refuge from a closed-minded and dehumanizing military culture. I have attained a sense of purpose that I’ve never had in my life…. Under the Hood has changed my life forever.”