Listening Process (Section 5) – What roles can veterans, soldiers and military families play in ending war?

We interviewed members of Iraq Veterans Against the War, Veterans for Peace, Service Women’s Action Network, and other organizers who are military veterans or military family members. We also asked all of our interviewees about the role of soldiers, veterans, and their families in ending war, and how others can best support their efforts. Most everyone felt that they are uniquely positioned to organize in ways that others cannot, particularly in organizing active-duty GIs. Our interviewees unanimously saw veterans as effective spokespeople, and many folks viewed them primarily as such. The vets themselves were more excited about organizing their peers. They tended to describe support in practical terms: lending a hand with logistics, raising money, etc. Some veterans saw themselves as particularly well positioned to connect with working-class constituencies and help build a more broad-based movement. Challenges they named include struggling with trauma from their experiences, coming out of a culture that discourages dissent, balancing activism with personal and economic needs, dealing with a movement that they often find alienating and unstrategic, and finding adequate funding and resources to carry the organizing work forward.

The most important thing about Veterans For Peace is that we are vets. Many of us have been to war. All of us are trained to fight. We know what war is about. In the public eye, we have credibility. We want to use that privilege to struggle for peace and justice. Some of our programs involve educating people about what war really is. Part of that is counter-recruitment or truth in recruiting. Also sharing our experiences, going to speak to Congress, writing letters—what the average citizen does, but because we are or were soldiers, airmen, seamen, marines, people tend to listen to what we have to say more. At the beginning of the current war in Iraq, we created space for other people to be able to speak out and not be demonized as easily, with us standing with them. We certainly helped military families feel more comfortable speaking out against the war. It’s very difficult for a military family person to do that, but when they see that there are other people associated with the military doing this, then they can too. We’re kind of like a family. And then when the Iraq veterans came back, they had somewhere to go, to help them get off the ground and organize themselves. Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) is growing their organization. The average person who comes off active duty or out of the war doesn’t necessarily want to get politically involved. That’s one barrier. Another is the cultural divide. If the perception of IVAW by people on active duty is that they’re too ensconced in a culture that they don’t like, then they’re not going to join. So if the peace movement, in trying to help, is creating that image, then that’s not very helpful. People need to think about how they’re supporting the vets and make sure it’s not so colored that it diminishes what IVAW is trying to accomplish with their outreach. If other groups can act as a support mechanism, that will allow us veterans to be able to do the things that we can do, that nobody else can do.

—Michael McPhearson, Veterans For Peace

During the Vietnam War, the role of active-duty soldiers and veterans was a key factor in strengthening the movement and building pressure against the war. In 1970 and ’71, when Vietnam Veterans against the War (VVAW) really emerged in the public arena, it caused enormous distress and heartburn in the White House. We know from his own memoir that Chief of Staff J.R. Haldeman said to Nixon, “These guys are killing us in the media.” And Attorney General John Mitchell called VVAW the most dangerous organization in America, by which he meant the most effective at organizing against the war.

Voices from the military are given prominence. On the one hand they deserve respect for the sacrifices they made, but it’s also a reflection of our unfortunately militarized culture. We need to take advantage of this because so many of those who serve in our military know better than anyone else just how foolish and unjust our American policy objective is. They absolutely need to be elevated as primary voices of our movement.

It’s necessary to recognize the differences between the Vietnam and Iraq eras. Today they are in a volunteer force—they don’t have opportunities for education and employment, and most are married or have children. They cannot afford to get out. In our day, we couldn’t wait to get out; part of our organizing was to get out. Many of us could figure we’ll go on to college and figure something out. We have to be more patient with and understanding of the military community.

—David Cortright, Fourth Freedom Forum

There is an ongoing tension about how much do we want vets at the front of the movement. Is this about stopping this war or about ending militarism? You can get a lot of military families to support you on the first one, but when you start talking about radical downscaling of the arms industry and the size of the military, that’s a whole different ball game. That tension is always there.

—TJ Johnson, Port Militarization Resistance

Veterans and resisters are central to building the antiwar movement. Many of them are newly politicized from their own experiences; in the United States, there tends to be a lot of emphasis on the deaths of soldiers, and a serious under-emphasis on the deaths and suffering of Iraqi people and Afghani people. It becomes really intolerable, especially for people from those regions and the Third World in general. There’s a minute spent talking about a million people—Iraqis who have been killed—and so much time on how many military personnel are injured and their conditions. We went to a workshop at the U.S. Social Forum in Atlanta with all of our youth, who are doing a counter-recruitment campaign. It was led by soldiers of color who are resisters or have been in Iraq. It seemed to me that nobody was really challenging people on a deeper level to think about how—as people within the United States—we have a responsibility to understand that the level of oppression of the people being bombed is far, far greater than the level of oppression of soldiers. It’s a constant issue for our community—it’s really hard to feel invisible even within antiwar circles. That kind of politics really needs to be pushed. During the Vietnam War, global conditions were different and there was a real sense of internationalism in the movement. There needs to be more of that in today’s antiwar movement.

—Monami Maulik, Desis Rising Up & Moving

In my experience, I don’t think the veterans groups or military families protesting this war have fallen into the problem of, “It’s all about us, and it’s not about the Iraqis.” That’s a real challenge in an antiwar movement in an imperial country: how do you talk about the impact on people in and from the United States when the most impacted people are in the country under occupation?

Racism is beaten into our heads all the time, particularly the attitudes toward Arabs and Muslims in a post-9/11 world. Challenging that dehumanization has to be an integral part of any antiwar movement. It’s always complicated how you do that, how that translates into a leaflet or demand or campaign. In the talks I’ve heard, demonstrations I’ve seen, things I’ve read, I think most of the messages that have come out of the GI resistance movement have been quite sensitive to the humanity of the Iraqis. Not every single thing. But I tend to think they’ve done a very good job on this point overall, and I don’t feel at all hesitant about supporting the veterans, soldiers and military family antiwar groups.

—Max Elbaum, War Times

The young folks coming home are a really important generational voice about what war is. We need to strengthen the alliance between active GI organizing and grassroots movements outside the military—a critical lesson from the Vietnam era. And whether we’re out of Iraq in a month or five years, we need to make sure the political lessons of this occupation continue to resonate and that our government can’t do this again. Some of the most important voices that will make that possible are going to be the veterans. Long-term, they are one of the most important bases for the antiwar movement to be building.

One way to support veterans’ organizing is resources. We need more vets who are in a position to be out organizing other soldiers and vets. We need to be in the role of supporting their organizing, amplifying their voices—to make sure they’re getting the support and training that they need to be organizers—instead of expecting a constituency that is struggling to heal from the shattering effects of war to organize from scratch and on a shoestring. I’ve seen projects where vets are expected to go from zero to 60. And the antiwar movement kind of uses vets to legitimize our work, rather than legitimizing veterans’ work and supporting their efforts to mobilize their own constituencies.

—Patrick Reinsborough, smartMeme Strategy & Training Project

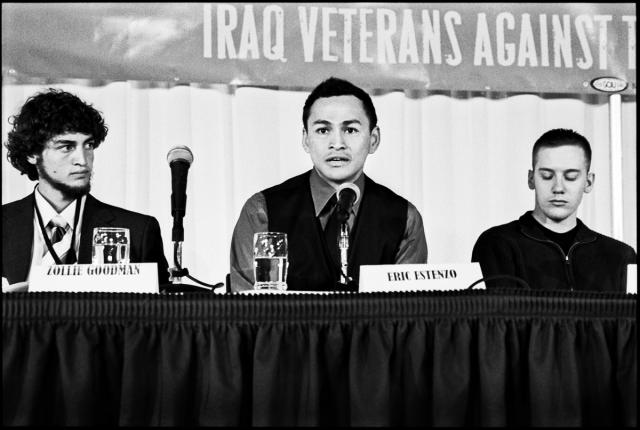

IVAW’s three goals are: immediate withdrawal of all occupying forces from Iraq, full veterans benefits, and reparations for the Iraqi people. Our strategy to end the war is to withdraw military support from the war.

—Kelly Dougherty, Iraq Veterans Against the War

I’m a firm believer that you should exert yourself where you have the most influence. IVAW’s strategy is to undercut military support for the war. If you think about all the things that support this war— corporations, big oil, Congress, the executive branch —those are all things that none of us can do anything about. There’s too much money. There’s too much political power. Where we have the largest impact, as IVAW, is on the military community. There’s a mutual respect among every veteran I’ve met, especially every combat veteran. Regardless of your views on the war, you look at each other and you say, “You’ve experienced the same things that I’ve experienced.” I think organizing military bases is where we can have the most impact. If other organizations could help us get a larger presence around military bases—get us help organizing—I think that’s going to have a great impact. The philosophy is that if they don’t have soldiers to fight the war, they can’t fight the war no matter how much money they have. We see what helped end the Vietnam War was that all these soldiers said, “No. We’re not going to do this anymore. This is screwed up.” That’s what we want to do.

—Jason Hurd, Iraq Veterans Against the War, Asheville, NC Chapter

The government simply cannot fight sustained wars and maintain occupations without enough personnel. Strategically, on a very practical level, when GIs resist—and there’s a whole spectrum of resistance, from outright refusal, to not re-enlisting, etc.—it means the military leadership is being held accountable by those asked to sacrifice. This is a powerful way that people can impact foreign policy.

The movement is concerned mainly with public resisters; if we continue on that path, we’re always going to have a thin stream of people. You won’t read about most of the people I support because they don’t make their cases public. Supporting GI resistance to illegal war is about more than making headlines. Resisters need funds for their legal defense, help providing for their families, mental health care, as well as political support and media guidance. Our real work in stopping the war is not going to be all bright lights. It’s going to be some hardcore, long-term work. Right now, many veterans’ and church groups are committed to supporting vets for the long run. I would love to see more organizations orienting that way.

—Aimee Allison, Army of None

When I visit the Veterans Affairs hospital I see vets from the Korean War who are still dealing with their issues when it comes to benefits, and nobody is there to support them. So what kind of vet do we support?

Definitely there needs to be more understanding. We have this assumption that they’re all the same and we have one box that we put them into, but there are different types of vets—not just in terms of gender or race, but culturally how they are affected by their diverse experiences in the service. I think this is lacking in a lot of veterans groups and in the peace movement. We also need to start figuring out what our support work, after this war, is going to look like.

—Maricela Guzman, Service Women Action Network

There are all different categories of support, including political pressure (like public support campaigns), legal, economic, moral, emotional, often spiritual. We need to break those down and understand who is doing what and how we can strengthen that. Groups should make that part of their organizing. We’re not asking everyone to be Courage to Resist or IVAW or WRL, but I think it’s about making military resistance a key part of your work and identifying what resources you have locally. What can you do? For example, with church members: Can you become a sanctuary for war resisters? You start by identifying the strengths within your own community.

—Lori Hurlebaus, Courage to Resist

There is a tendency for groups to get excited about having war resisters come talk to high school classes about their experiences. It’s true that we need to get these voices and stories to our young folks so they don’t enlist and so communities understand the dangers. At the same time, we often don’t give vets the space to go through what they need to go through, to take care of their own lives.

That’s one of the pitfalls we’re seeing in Portland: there are peace groups that really want to support an IVAW chapter here, but we don’t have vets that are in a place to do that right now. There are a couple who do have an interest, but it’s important to provide the space to let them do it in their own time. We can do some of the ground work and say, “You’ve got community support to make this happen, and we’ve got funding and other stuff ready for you.” But it’s about letting go of the reins a little bit and saying, “Hey, these aren’t our reins to hold.”

—Pam Phan, Opt Out Street Project (AFSC)

We’re tired of being window dressing for other people’s events. However, working with other groups allows us to not have to re-invent the wheel. IVAW members are often green when it comes to organizing— lacking nuts-and-bolts skills that a lot of activists have—others can bring that to what we’re doing. Something as simple as getting a permit; an IVAW member might not know the process, whereas another activist has done that tons of times. Bringing food to our strategy session, providing transportation or lodging—all of these things are really helpful. In the military it’s what we call a “force multiplier”: things that add to your ability to conduct your mission. For every grunt in combat on the front lines, there are nine other soldiers doing essential support work. Somebody has got to get the bullets there, food, the mail; somebody has to do the medical. So what we call “combat support,” other groups can provide. If the best thing that we have to offer is our credibility, then free us up to be the people in the front, on camera.

Being able to connect with other young people who care about politics and ending the war is really empowering for a young vet who is just raising their own consciousness. To meet another young student who is sort of at the same place but has different experiences, for them to be able to grow together and hang out together and laugh together and struggle together—that is really powerful for a lot of our members. In IVAW, the camaraderie is a huge asset. It’s probably saved a couple of people’s lives, actually. They meet up with other members and realize, “I’m not alone. It’s okay for me to be against what I just did.” That’s enormously important. I think being able to share that with other young people is also powerful and cathartic.

—Jose Vasquez, Iraq Veterans Against the War, NYC Chapter

Next Section:

What is the relevance of nonviolence today?Previous Section:

How do we build a more multiracial and cross-class antiwar movement?