My Favorite Issue: WIN’S First Year, 1966

WIN first appeared January 15, 1966. It was published by the New York Workshop in Nonviolence, sponsored by both Committee for Nonviolent Action (CNVA) and War Resisters League. The timing was fortuitous. WIN appeared as the United States was entering years of tumult. This rapidly changing world gave WIN a variety of opportunities and challenges, including:

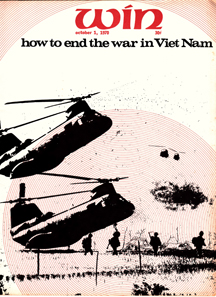

- The Vietnam war was tiny but steadily growing bigger. More and more U.S. soldiers were coming home wounded or in body bags. Opposition to the war was also escalating. WIN’s role became reporting on nonviolent direct action against the war, especially civil disobedience. It also reported on the wide range of writing about the war and nonviolence.

- This was also the era of the Human Be-In, of flower power, of dancing in the parks and on the beaches. Youth culture blossomed. WIN covered these peaceable happenings fully. Our pages were infused with positive energy, a certainty that although our work is urgent we should strive to accomplish our tasks with joy, simplicity, and love for each other.

- The New Left was also flourishing. These educated youngsters tended to be more interested in tactical nonvi- olence than pacifism, and they loved to argue. There were debates between those fully committed to nonviolence and those who had doubts. These tensions and arguments spilled into the pages of WIN. Perhaps some of us learned a little from one another.

- This was the golden age of the Underground Press. WIN proved to be just barely hip enough and funky enough to sometimes be considered a part of the counterculture — with- out being too offensive to more staid and older pacifists.

- And it should be pointed out that we were part of a world encumbered by towering white male privilege. Perhaps we nonviolent activists were a bit more enlightened than the country at large but we had enough racial prejudice, sexism, and homophobia to give us things to work on for years.

With all this in mind, let’s look at Issue No. 1.

The lead article is “The Washington March,” by Martin Jezer—with the delicious subtitle, “proselytizing the liberals.” It is followed by reports by Don Newlove and Bradford Lyttle, respectively, on a peace rally at New York City’s Herald Square during the Christmas rush and a civil disobedience demonstra- tion (14 arrests) at the Boeing-Vertol helicopter factory near Philadelphia. The next 10 pages are devoted to reviews—written mainly by Paul Johnson—of books and magazines about the war.

All in all, an excellent issue, both hip and well written.

No editors are credited. A staff list did not appear until Issue 3, February 11, 1966. It named Marty and Paul as “editors this issue.” They were the ones who had persuaded the Workshop in Nonviolence to publish a magazine. Other staff members listed are Henry Bass, Judy Brink, Maris Cakars, Leonard Fetzer, Rebecca Johnson, Dorothy Lane, Martin Mitchell, Gwen Reyes, Bonnie Stretch, and Robert Sievert.

Maris Cakars was the third major figure at WIN. When the magazine began, he thought of himself primarily as an orga- nizer and was concerned that work on the magazine might take energy away from organizing demonstrations—the heart of the Workshop; but by issue 2, January 28, 1966, Maris stepped up as a writer, contributing a strong essay, “The Political Relevance of Public Witness.” And it was Maris who championed WIN for years.

Maris Cakars was the third major figure at WIN. When the magazine began, he thought of himself primarily as an orga- nizer and was concerned that work on the magazine might take energy away from organizing demonstrations—the heart of the Workshop; but by issue 2, January 28, 1966, Maris stepped up as a writer, contributing a strong essay, “The Political Relevance of Public Witness.” And it was Maris who championed WIN for years.

Issue 3 also contains the first examples of what is probably WIN’s greatest contribution to journal- ism—coverage of demonstrations with first-person accounts by several participants, woven together to create vivid, multi-di-mensional reports. The same issue also marks the first appear- ance of Henry Bass’s “Alphabet Soup,” an effort to make sense of the myriad progressive organizations known by their initials.

Issue 9, May 28, 1966, includes a reading list. WIN invited writers and activists to recommend books. Responses came in from journalist Nat Hentoff; poet Allen Ginsberg; WWII conscientious objector and anitwar coalition genius Dave Dellinger; co-founder (with folk singer Joan Baez) of the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence Ira Sandperl; WRL’s David McReynolds; playwright Arthur Miller, writer and labor organizer Sidney Lens; two profoundly influential pacifist thinkers, A.J. Muste and Barbara Deming; and critic Edmond Wilson, although Wilson refused to recommend any books. Amazingly, no book was recommended twice.

With Issue 16, October 5, 1966, WIN went national, distributed by both CNVA and WRL, and I became managing editor. I found myself working on an exciting and relevant magazine, well edited and well written by the peace workers and writers who started it, helpful to and loved by nonviolent activists everywhere and making a real contribution. We were off on the long, difficult, and gratifying struggle to end the Vietnam War.