Roberto Martinez: The Struggle to Overcome the U.S.-Mexico Divide

At 6:30 a.m. on May 20, agents from the U.S. Border Patrol and the Transportation Safety Administration descended on a trolley station near downtown San Diego. After questioning commuters about their U.S. residency status—allegedly because they were behaving suspiciously—agents detained 21 individuals, three of whom were teenagers on their way to their high school. Later that day, having made the determination that the three minors were in the United States “illegally,” the Border Patrol deported them to Mexico, thus dividing them from their parents and siblings living in San Diego.

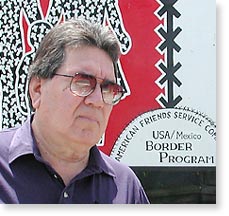

Around the same time that the raid was taking place in downtown San Diego, Roberto Martinez, 72, passed away at his home in nearby Chula Vista. A long-time Chicano, border, immigrant, and human rights activist, Martinez served for 18 years as the director of the U.S/Mexico Border Program of the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in San Diego. It was abuses such as those at the trolley station that day that Martinez vigorously contested and organized around for much of his life.

In a number of ways, Roberto Martinez’s life embodied many of the struggles that people of Mexican descent in the borderlands have experienced. Despite being a sixth-generation Mexican-American, U.S. authorities often harassed him in his youth in his native San Diego, accusing him of being “illegal.” For instance, during the infamous Operation Wetback in 1954, when the Immigration and Naturalization Service rounded up and deported more than one million suspected unauthorized migrants of Mexican origin, immigration agents frequently came to Martinez’s after-school workplace and dragged him out.

In the 1970s, racist vandals attacked his home in Santee, at the time an unincorporated part of San Diego County, where he lived with his first wife and five children, scrawling a message on a wall, “This is a white neighborhood.” And throughout his three decades as a migrant rights advocate, he had to endure harassment and threats from opponents. Nonetheless, he persisted, protecting, teaching, and inspiring many along the way.

Compared to when Roberto was a young man, the boundary and immigration enforcement apparatus today is far more formidable—especially in the San Diego area where many miles of double layers of wall and fence now litter the landscape. At the time of Operation Wetback, there were less than 1,100 Border Patrol agents nationally. Today, there are more than 18,000—representing a fourfold increase since 1994, when the Clinton administration implemented Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego, the centerpiece of its national effort to “regain control” of the U.S.-Mexico divide, one that intensified greatly in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

In addition to an intensified surveillance of many communities in the borderlands, recent years have seen a dramatic increase in migrant deaths (more than 5,000 bodies have been recovered in the U.S.-Mexico borderlands since the mid-1990s) and deportations—and with it scarred children and parents and divided families. According to a report published in April by Human Rights Watch, between 1997 and 2007, deportations separated more than one million family members in the United States from a parent or spouse. Over 70 percent of the deportations were for nonviolent criminal offenses, including possession of marijuana and traffic violations.

During the 1990s, I had the pleasure and honor of meeting and speaking with Roberto Martinez on a number of occasions in San Diego. I vividly remember his stressing to me in one of our first conversations that the U.S.-Mexico border destroys families and communities. As illustrated by the deportation of the three teenagers on May 20—among countless other cases—his words remain tragically true.

Roberto Martinez courageously and consistently demonstrated through both his words and actions that the border and its logic of division and exclusion are not to be endured, but to be contested and overcome. In this sense, to quote Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano, “Reality is not destiny, it is a challenge.”

Postscript: In mid-June, U.S. authorities granted emergency humanitarian visas to the three high school students, allowing them to reunite with their families in San Diego. The three had spent the previous month in Tijuana—where they have no relatives—living with a local woman who provided them with food and housing. The visas do not mean that the teenagers will be able to permanently stay in the United States, only that they will be able to have their cases heard in immigration court. The U.S Border Patrol maintains that it acted rightfully in arresting and deporting the youths.