“On the Side of Revolutionary Democracy”

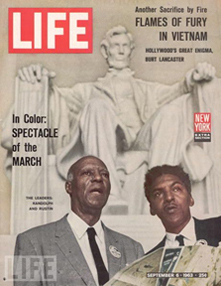

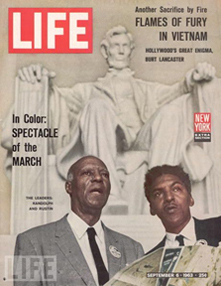

A Speech by Bayard Rustin

Speakers at a historic 1965 Madison Square Garden rally against the war in Vietnam included U.S. Sen. Wayne Morse (D-OR), Coretta Scott King, Dr. Benjamin Spock, and the great Bayard Rustin, then on the WRL staff. Held on June 8, 1965, and sponsored by the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy, the rally was one of the first large-scale actions against the war and brought together a broad array of peace advocates, from centrists Morse and Spock to Rustin, who was a WWII conscientious objector, civil and gay rights pioneer, nonviolence mentor to the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and architect of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. In Rustin’s speech, he assailed the war, declared that the United States should be standing “on the side of revolutionary democracy” around the world, and called for proponents of peace to go out in the streets to demand it. (Some 2,000 members of the audience heeded the call by marching to the United Nations after the rally.)

This year marks the 100th anniversary of Rustin’s birth, and WRL is helping to lead the celebrations of his life and his massive contributions to the causes for which we stand. Herewith is his draft of the speech he made that night, previously unpublished and soon to appear in a new book co-published by PM Press and WRL: We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and Militarism in 21st-Century America, edited by Mandy Carter, Elizabeth “Betita” Martínez, and Matt Meyer, with a foreword by Cornel West and afterwords/poems by Sonia Sanchez and Alice Walker, due for release this August.

“On the Side of Revolutionary Democracy”

Though Congress refuses to admit it, we are at war. It is a useless, destructive, disgusting war. We must end the war in Vietnam. It harms people on both sides. It reveals the bankruptcy of America’s foreign policy. The bombings, the torture, the harassment and the needless killings are abhorrent to me, and to all civilized men. Therefore, I am for supporting any and every proposal that is humane and relevant, that will end the war in Vietnam.

I am not a military strategist, I have never been one, and after observing the Pentagon mentality, I don’t want to be. President Johnson has admitted this is a fruitless war, that no one can win—neither the northern regime, nor the southern regime. If that is true (and who here has reason not to believe him) then we must accept negotiations and not through the back door and not with any face-saving devices. We must negotiate now! Period. If in order to negotiate, Hanoi insists that the Viet Cong must be part of those negotiations (and the United States says the Viet Cong is dominated by Hanoi), isn’t it ridiculous to agree to sit down with Hanoi but not with the Viet Cong? The United States cannot continue to insist on negotiations only with Hanoi and not the Viet Cong. We must sit down with all interested parties. We must forget mutual recriminations and diplomatic hedging and arrogance—and we must negotiate now!

For years in Vietnam, the United States supported the Diem government, which was undemocratic and became increasingly unpopular. It was a government restricted to the backing of a religious minority. Diem was incapable of carrying out the social and economic reforms which were periodically announced (and just as periodically forgotten). And after fiasco after fiasco when we finally realized how catastrophic this American position was, the people of Vietnam were either sympathizing with the Viet Cong or else they were utterly demoralized. And the best that the United States could do was to govern by military fiat and by coup d’état.

We have not learned from this experience. Even now in the Dominican Republic we are repeating this sterile policy in even more tragic form. We did not have to seek out democratic forces in the Dominican Republic. They existed in the government of Juan Bosch. yet, we stood idly by when Bosch was overthrown by rightist generals. And then, when there was a popular movement in support of Bosch, and democracy, we intervened on the side of the generals again and on the side of social reaction. The reason we gave was that there were Communists there—54 or 55 or 58, the numbers game changed rapidly. Do the so-called political realists say that wherever there are 50 or so Communists in the midst of a popular democratic revolution, those Communists must inevitably take over? If they say so, then the Pentagon and Mao are one in agreement. In the Dominican Republic, in Vietnam, we must be on the side of revolutionary democracy. And, in addition to all the other arguments for a negotiated peace in Vietnam, there is this one: that it is immoral, impractical, unpolitical, and unrealistic for this nation to identify itself with a regime which does not have the confidence of its people. (And it is tragic for us, in effect, to allow communism to appear over and again as the defender of democracy and change).

Vietnam and the Dominican Republic show how America’s war hawks have proven themselves as up-to-date as the dodo bird. I say to the President: America cannot be the policeman of this globe! If we are going to send the Marines into every Latin American country that has 50 or so Communists in the middle of a revolution, if we are going to move every time Communists take one side or another in revolts in Africa, if we are going to be the patron of all the right-wing generals in Asia, then we are damned to move tragically from disaster to disaster. We will not only have the wrong policy. We will have an overextended fatal policy all over the world.

I am not an isolationist. Let me say that America has the funds to give massive aid to Vietnam and Southeast Asia, and to carry on in the United States a vast program or social reconstruction. But the fact is that the present war psychology diverts planning and programs from what in fact will help people (in Vietnam or in Mississippi). This war psychology diverts creative energy to an infantile faith that biological agents, chemical warfare, and crude power can sustain freedom and democracy. The continuation of this fruitless war is the continuation of a psychology that will permit the American people to tolerate longer the suffering of America’s 50 million poor. It will permit reaction to spread in the name of patriotism. And it will force us to seek military solutions to problems that are purely political (as is being done in Santo Domingo), and it will divert attention and energy from the struggle for racial equality in this country—America’s first need, if we are to dare to speak of democracy abroad.

The civil rights movement has double responsibility in this period. We must see to it that rightists do not use the threat of communism to begin another witch-hunt. We have seen that they will begin with SNCC, CORE, and Martin Luther King. We must continue to build up alliances of forces necessary for progressive social change. Moreover, we must apply the slogan of “one man, one vote” internationally—in Saigon, Hanoi, Formosa, in Spain and in Peking and Moscow and even Havana, as well as in Mississippi. And we must join with the progressive elements of this society to end the war in Vietnam.

Therefore, I advocate the following:

- We must declare our willingness to negotiate with all parties;

- We must lift the blockade;

- We must immediately halt the bombings of North Vietnam;

- On humanitarian grounds, we must send food, clothing and medicine to the people of North Vietnam—with only one string attached: that the food go to the underclothed, the unfed, and the sick.

- We should repeat our willingness to invest funds in the economic development of South Vietnam and Southeast Asia, but we should add: we will do this through an international agency and under international control.

One hopes to God that before it is too late, this country will finally learn that in the year 1965 workers and peasants, whether they are in Mississippi or South Vietnam or North Vietnam, are searching for dignity and freedom from domination. Together, they are more powerful than American troops and the vast American arsenal. Today, the making of the peace—which was once an activity pondered only by utopian thinkers—has now become an urgent and practical political necessity.

The actor Ossie Davis recently pointed out that we must say to the President: “If you want us to be nonviolent in Selma, why can’t you be nonviolent in Saigon?” All the weapons of military power, chemical and biological warfare, cannot prevail against the desire of the people. We know that the Wagner Act, which gave labor the right to organize and bargain collectively, was empty until workers went into the streets.

The unions got off the ground because of sit-down strikes and social dislocation. When women wanted to vote, Congress ignored them until they went into the streets and into the White House and created disorder of a nonviolent nature. I assure you that those women did things that, if the Negro movement had done them, they would have been sent back to Africa! The civil rights movement begged and begged for change, but finally learned this lesson—going into the streets. The time is so late, the danger so great, that I call upon all the forces which believe in peace to take a lesson from the labor movement, the women’s movement, and the civil rights movement and stop staying indoors. Go into these streets until we get peace!

– Bayard Rustin