Talkin’ Union: 3,000 Years of Nonviolent Resistance

“We are dying,” wrote a group of 12th-century B.C.E. workers to their bosses, in a collective plea for their overdue pay. When they got no response, they committed history’s first known act of nonviolent resistance.

At the time, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt were having the great tombs built for themselves near their capital at Thebes, some 500 miles south of the mouth of the Nile. Not far from the construction site was a village in which the stonecutters, masons, carpenters, potters, and other skilled workers lived with their families. The necropolis and the village are now called the Valley of the Kings and Deir el-Medina, respectively.

Egypt’s was not a cash economy. The state paid the workers in food and goods, the most important of which were wheat for flour and barley for beer. But some time around 1155 B.C.E., an economic crisis and government instability slowed deliveries to Deir el-Medina. The workers protested to the capital. “We cannot live … [without our rations],” they wrote. The rations were sent, but then delivery slowed down again. As a last resort, the workers went to the construction site, where they sat down and refused to work until the problem was solved. It was the first recorded strike in history.

Withholding labor is one of the most obvious and potentially effective ways that unarmed people can resist. But for almost two millennia after Deir el-Medina, there were few strikes. The slave-labor and feudal societies that followed Egypt provided far more dire penalties for workers who stood up; disobedience meant death, and slaves and serfs dared not rebel unless they were armed. Additionally, feudalism’s micro-economies provided far fewer mass workplaces.

Some 2,300 years after the Egyptian strike, however, in the 12th century C.E., the nations of Europe began to find new sources of wealth. They turned east first, via the Near East incursions called the Crusades and the Far Eastern trading expeditions of Marco Polo and his successors. Then, one after another, they sailed west to the Americas and south to Africa, where they seized the riches of continents from the continents’ peoples (often seizing the peoples as well).

The result was a drastic change in European demographics, lives, and economies, bringing about greater specialization of work, a mass migration into the cities, and the growth of a middle class. Those changes collectively set the stage for the even greater changes of the Industrial Revolution, which would give birth to a class of industrial workers and lead to the long struggle for workers’ rights and a rich two-century history of nonviolent actions in furtherance of those rights—far more than can be told here. What follows are a few significant moments in that history.

‘We Have Injured No Man’

The laws of the industrializing countries were, to say the least, slow to recognize workers’ rights. England, for instance, outlawed unions in 1799 via the first Combination Act, the full title of which was, “An Act to Prevent Unlawful Combinations of Workmen.” But the tide had turned, and the Combination Acts were repealed in 1824–25.

A few years later, in the early 1830s, England was gripped by a recession. Wages dropped across the country. In the town of Tolpuddle, in Dorset, six farm workers joined together as the Friendly Society of Agricultural Laborers, swearing a solemn oath not to work for less than ten shillings a week.

But if unions were now legal, swearing collective oaths was not, under an old law meant to prevent mutiny aboard ships. In March 1834, the six members of the Friendly Society were tried in Dorchester on the charge of “administering an unlawful oath,” before a jury that included the landowner who had brought the charge against them and a judge who had declared before the trial that their actions threatened society. Non-capital felonies were punishable by “transportation”: convicts were shipped to Australia for fixed terms. All six members of the Friendly Society were convicted and sentenced to seven years’ transportation.

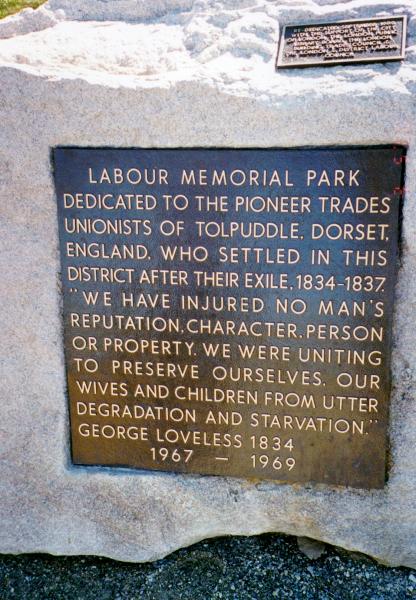

The “Tolpuddle martyrs” became heroes to the growing British labor movement. When they were freed, some returned to Dorset, and some emigrated to Canada. Plaques in Plymouth, England, and London, Ontario, commemorate their contribution to trade unionism.

Bread and Roses, Mines and Mills

In British and U.S. mines and mills, industry’s “robber barons” sought maximum productivity for minimum cost, paying the lowest possible wages, demanding the longest possible hours, and spending as little as possible on luxuries like workplace safety. Women and children worked 70-hour weeks in the textile mills for pennies, dying young from fibers in their lungs; men went down into the coal mines that powered the mills and perished in cave-ins and gas explosions, or died young of coal dust in their lungs. In the company towns, families lived in company-owned barrack- and tenement-like homes, spending most or all of their meager incomes on rent and groceries at company-owned stores. When they tried to seek living wages and safer conditions through collective action, the industrialists’ friends in the legislatures outlawed unions or outlawed strikes; if those expedients failed, the owners brought in armed strikebreakers. Indeed, organizing and striking were so hard, and punished so stringently, that workers often struck only when owners proposed to lower already low wages.

In January 1912, in one case among hundreds, mill owners in Lawrence, Mass., threatened to lower wages. Some 20,000 immigrant women and children mill workers, organized by the Industrial Workers of the World—the IWW, or “Wobblies”— struck the city’s mills in an action that became known as the “Bread and Roses” strike. The mill-friendly police jailed the IWW organizers and turned fire hoses against picketers in the bitter winter cold. The union sent reinforcements: its most famous and effective speakers, including “Big Bill” Haywood and “Rebel Girl” Elizabeth Gurley Flynn. Then the police went too far. The strikers attempted to send their children out of the beleaguered city, and police clubbed mothers and children at the railroad station to prevent the emigration. The ensuing publicity brought national attention to the strike, and in March, after two months, the mill owners agreed to a 5 percent raise for all the workers.

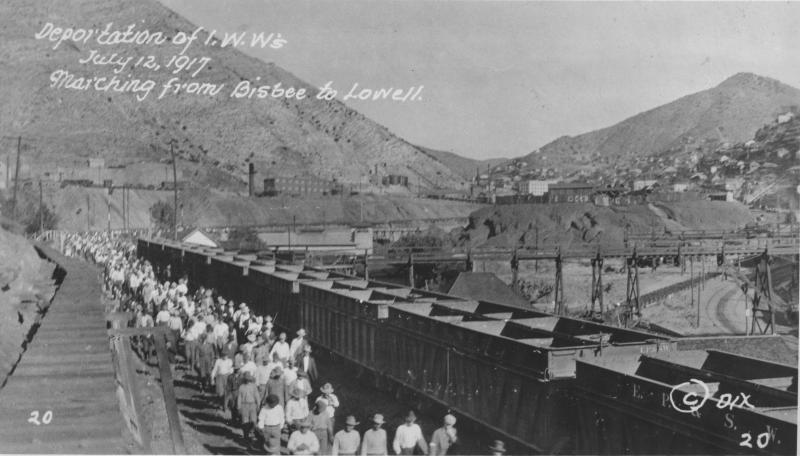

What happened a few years later at the end of a miners’ strike in Bisbee, Ariz.., wasn’t one case among thousands. It was and remains unique in U.S. labor annals: the deportation out of the state and into the New Mexico desert of more than 1,100 alleged strikers.

World War I had brought boom times to the copper towns of the West and created a fertile field for organizers from unions including the IWW. In late June 1917, the IWW called a strike against Bisbee’s mines. The companies, including Bisbee’s biggest employer, Phelps Dodge, struck back: On July 12, a 2,000-strong posse seized the town’s telegraph office, cutting off communication with the outside world, then rounded up more than 1,100 men (not all of them strikers). The posse marched the men two miles to a ballpark, where the prisoners were offered a chance to renounce the strike. Then 1,186 men were forced onto manure-filled cattle cars and carried to Columbus, N.M., where they were left without food, water, or shelter. Two days later, federal troops rescued them.

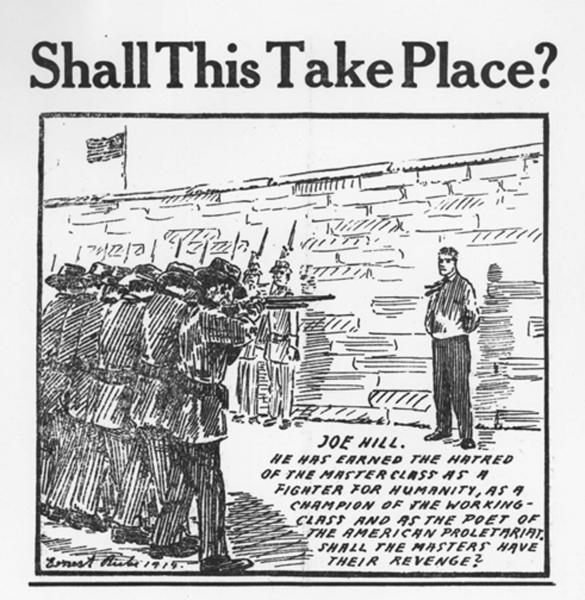

The Wobblies were also known for their skillful use of one important tactic in labor’s nonviolent toolbox: music. Many IWW songs became labor classics, including Joe Hill’s “The Preacher and the Slave,” with its immortal line, “You’ll have pie in the sky when you die.” Indeed, Wobbly Ralph Chaplin’s “Solidarity Forever” became the unofficial anthem of the entire U.S. labor movement. Not until Dust Bowl and Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) balladeer Woody Guthrie would a non-Wobbly write as many rousing labor songs.

Escalating Nonviolence

Clearly, the fact that withholding labor is an intrinsically nonviolent act didn’t prevent employers—and, often, governments acting on the employers’ behalf—from responding violently to union organizing efforts and strikes. Over and over, local police forces, government troops and agents, and private militias and mercenaries assaulted strikers and picketers, jailed them, shot them, and from time to time executed them after framing and convicting them on capital charges. Two of the most notorious U.S. instances of such judicial murders were the execution of four Chicago anarchists in 1887—the “Haymarket martyrs”—and the 1915 execution of legendary IWW organizer and songwriter Joe Hill.

Yet the tide was with labor at last, especially during and after the Great Depression. By the mid-20th century, as many as one third of U.S. industrial workers were represented by unions and were consequently enjoying the highest standard of living working people had ever known. Still, large segments of the labor force were not included. Many manufacturers had fled south, where segregation kept Black and white workers divided and made organizing difficult or impossible; migrant workers, too, remained apparently unorganizable. New kinds of organizing and new strategies and tactics were needed.

They arose. Migrant workers, mostly Mexican or Chicano, had always been a mainstay of central California’s lush farmlands. The Wobblies had tried to organize there in the 1910s, as had the CIO in the 1930s. All had failed. Two Wobbly organizers went to prison after a 1913 assault by sheriff’s deputies on a picket line at a farm in Wheatlands. In the 1940s, Woody Guthrie penned two of his loveliest songs about California migrants: “Pastures of Plenty” and the haunting “Plane Wreck at Los Gatos Canyon.”

But in 1962, Chicano activists César Chávez and Dolores Huerta co-founded the United Farm Workers—and found a way to supplement the workers’ bargaining strength. Chávez, a committed pacifist, followed the nonviolent path of Indian leader Mohandas Gandhi. In 1968, the union organized a boycott of California grapes and wine. Chávez’ 25-day fast in support of the boycott fired the nation’s imagination. Across the country, sympathizers boycotted California grapes for three years, finally bringing grape growers to the bargaining table in a first-time farmworkers’ victory. March 31, Chávez’ birthday, is a California state holiday.

Facing Off Against Global Capital

The Technological Revolution of the second half of the 20th century flung as many challenges into labor’s path as had the Industrial Revolution. Globalized technology and communications brought about globalized capitalism. Much U.S. industry moved “offshore” to the developing world, where even fewer laws protect workers than did in the United States and Europe during the Industrial Revolution. U.S. union representation sank drastically, with only about an eighth of the work force now included.

Labor has fought back with new nonviolent tactics and new alliances. In Argentina and elsewhere, workers faced with workplace closings have taken the failing factories over and run them cooperatively (see “Workplace Resistance and Self-Management”). Successful boycotts organized by local and national student-worker coalitions like Florida’s Coalition of Immokalee Workers have defeated immense corporations like fast-food giant Taco Bell. As this article was being written, the national United Students Against Sweatshops won its battle against Russell Athletic (a sportswear subsidiary of clothing titan Berkshire-Hathaway), which agreed to rehire 1,000 Honduran workers it had fired when they tried to unionize.

Labor’s centuries-long struggle remains a story without an ending. Whether workers and their allies will continue to choose nonviolent tactics remains to be seen. Certainly, however, the history so far suggests that when working people organize, they are always aware that, in the words of the great union anthem “Solidarity Forever,” “without our brain and muscle not a single wheel can turn,” Nonviolence works because labor’s collective hands hold “a power greater than their hoarded gold/Greater than the might of armies, magnified a thousandfold.”

Activist-writer and journalist Judith Mahoney Pasternak was the editor of this magazine (then called the Nonviolent Activist) from 1995 to 2005. Family lore holds that the first song she sang was Woody Guthrie’s “Union Maid.”

WRL Perpetual Calendar

WRL Perpetual Calendar