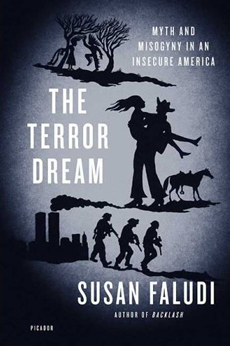

The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America

Empire’s Damsels

The Terror Dream: Fear and Fantasy in Post-9/11 America

by Susan Faludi

Metropolitan Books, 2007

368 pages, $26

With her latest offering Susan Faludi, author of Backlash and Stiffed, draws upon her previous insights into the causes and consequences of the antifeminist backlash of the last three decades, applying them to the era of the “war on terror.”

While many reviews have been positive, Faludi’s reception in leading newspapers lends support to her central thesis, that 9/11 set the stage fore a media and cultural regression toward vulgar gendered archetypes of heroic, protective men and retiring, weak women. The New York Times’ lead critic Michiko Kakutani wrote that Terror Dream not only is “sloppily reasoned” but gives feminism a “bad name” and is “one of the more nonsensical volumes yet published about the aftermath of 9/11” — no small feat in a field cluttered with Niall Ferguson’s Empire, sundry derivatives of Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations thesis, etc. Faludi herself may be the latest target of the tendency she documents among the nation’s arbiters of opinion to come down hard on women who refuse to conform to the role of passive victim or stick to the script that justifies war, torture, and occupation.

She notes that outspoken somen who questioned the drive to nationalism and war were attacked for their supposed lack of feminine decency: Katha Pollitt of The Nation, the critic Susan Sontag, and novelist Barbara Kingsolver were all subjected to over-the-top condemnations for what were, in retrospect, fairly mild statements of hesitation and caution.

In fact, the book is not nearly as bad as Kakutani would have us believe. Terror Dream is impressive in the scope of its documentation of our recent past and in its historical reach. For most readers, the account offers reminders of recent events too easily forgotten and serves as a primer on a strand of U.S. history too often overlooked.

Faludi documents the media’s post-9/11 campaign to redomesticate American women apparently “gone wild,” listing in detail the countless lifestyle, entertainment, and even news pieces that extol the virtues of pregnancy, passivity, marriage, motherhood and dependence. She homes in on the particular theme of women in need of male rescue — ultimately packaged (and fabricated) in the Jessica Lynch story — linking it to a long tradition of anxious American myth-making and finding its source on the Western frontier in “captivity narratives” by and about white settler women captured during the protracted, brutal wars of conquest against Native American lands and peoples.

Faludi convincingly argues that the myth of feminine passivity on the frontier had to be constructed through a preference for narratives that emphasized captives whose strategies for deliverance relied on Christian humility, physical passivity, and sexual purity. Tales in which captives instead opted for marriage and assimilation into Native American communities, or those in which women resorted to violent self-defense, accordingly fell by the cultural wayside.

It is this latter trajectory which is Faludi’s primary foil for the now mainstream, anti-feminist, rescue narrative. Hannah Duston is Faludi’s anti-heroine: a Puritan New England woman who, abandoned by her husband during a 1967 attack on their homestead, escaped her Abenaki kidnappers through effective, if bloody, use of a hatchet. Her exclusion from America’s foundational mythology is symbolized, for Faludi, by the sad state and physical isolation of the one statue raised in her honor.

It is at this juncture that Faludi’s feminism fails to live up to the full potential of its antiwar sensibilities. It is the implicit argument of the book that the antifeminist backlash since 2001 has helped to ensnare the United States is the ongoing ill-advised Iraqi adventure. But sadly, Faudi’s vision is trapped in the dream it documents; the ongoing war and occupation in Iraq, Iraqis and even their historical Native American counterparts on the frontier barely make an appearance in the central analysis in Terror Dream, existing largely as set pieces whose only function is to provoke the racist sexual anxieties of white men past and present.

Given Faludi’s resurrection of Hannah Duston’s cartoonishly violent femininity as an antidotes to our collective gender terror, one is left to wonder about possible exit strategies from the dreamscape. Other than Lynch, Duston’s closest modern-day corollary has to be Hillary Clinton and her brand of hard-nosed, pro-war competence. While her campaign, like Duston’s, may represent a particular strain of Annie-get-your-gun feminism, it offers little hope for the women and men, civilian and combatant, still embroiled in the ongoing horror that is U.S. policy in the Middle East.

One is left wishing that Faludi’s capacity to interpret dreams was as finely tuned to utopia as it is to nightmare. Readers might be advised to approach this book with the intention of expanding on Faludi’s limited historical imagination, with the aim of rethinking the country’s past, present, and future in ways more open to peaceful possibilities and to visions not rooted in imperial violence.