We Have Not Been Moved

WIN REVIEW

A Stronger Movement Against War

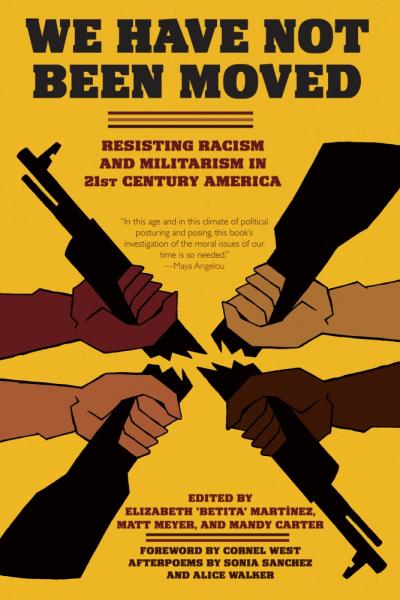

We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and

We Have Not Been Moved: Resisting Racism and

Militarism in 21st Century America

Edited by Elizabeth Betita Martínez, Mandy Carter & Matt Meyer with an Introduction by Cornel West

PM Press/War Resisters League; 608 pp; 2012

This impressive collection of essays, edited by Elizabeth Betita Martinez, Matt Meyer, and Mandy Carter, and put out by the War Resisters League in conjunction with PM Press, is a timely political contribution. The central theme of the book revolves around the challenge of building a viable antiwar movement that simultaneously challenges U.S. imperialism abroad and institutional racism and other forms of oppression at home. The editors offer up a broad collection of contemporary and historical voices who grapple with this fundamental challenge facing dissidents and dreamers in the United States.

Under the Democratic presidency of Barack Obama, the antiwar movement has entered temporary (one hopes) hibernation. Obama’s rhetorical departure from the war mongering Bush administration led many to believe that we would be entering a new era of U.S. foreign policy. Instead, we have seen a troop surge in Afghanistan, no end to the occupation of Iraq, lockstep support for Israel’s brutal treatment of the Palestinians, the bombing of Libya, and a proliferation of deadly drone warfare. Furthermore, Bradley Manning, a hero for the antiwar left if there ever was one, is languishing in a military prison for the crime of exposing the inner workings of U.S. imperialism.

However, in spite of the Obama administration’s hawkish policies, the antiwar movement is at a historically weak point. In the first few years of the war in Iraq, the infrastructure of the movement was capable of pulling hundreds of thousands into the streets. Today, national marches range in the thousands; the continuity is important, but the scale has been vastly reduced. Efforts around freeing Bradley Manning, and rallies in solidarity with the Arab Spring, are also important components of a new movement. But militant, large scale street demonstrations explicitly challenging the Empire’s wars abroad are missing from the political terrain. What was once a formidable national social movement is now largely a connection of smaller scale efforts with no viable national center capable of organizing and coordinating a mass movement.

However, the current impasse offers movement activists the opportunity to develop strategy and ponder. It is to the editors’ credit that the collection of essays does not attempt to put forward one political perspective, but rather allows the reader to engage in a series of debates from movement activists then and now. Early on, the tone is set by a fascinating debate between Robert F. Williams, head of the Monroe, NC branch of the NAACP and an advocate of black armed self-defense against white terror, and activists arguing for a policy of nonviolence in the civil rights movement. Williams, a Marine who served abroad during the Korean War, was radicalized by the disconnect between the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling and the harsh realties of continued segregation upon his return. In the face of white terrorism, Williams argued that Blacks should arm themselves and use violence in self defense. “The fact that any racial brutal- ity may cause white blood to flow as well as Negroes is lessen- ing racial tension.” Arguing against Williams, among others, is Martin Luther King Jr. He answers Williams with the following: “There is more power in socially organized masses than there is in guns in the hands of few desperate men.” One can imagine a new left that would incorporate such a culture of healthy debate, in which various strategies are debated with frank honesty and mutual respect.

As the book argues, a rejuvenated antiwar movement, if it is to survive and thrive, will need to be firmly antiracist. The ongoing (albeit downsized) occupation of Iraq and the war in Afghanistan have required heavy doses of Islamophobia. To challenge the logic of imperialism is to challenge the argument that Arabs and Muslims are incapable of democracy. But the book forces us to ask a deep question: How do we construct a viable antiwar movement in the United States that confronts the institutional racism right here at home? The section “Chicken and Eggs: War, Race, and Class” provides the reader with helpful historical context. In particular, Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s piece stands out as a lucid explanation of the connection between mass incarceration of people of color and militarism.

Several essays in the section “Where Do We Go From Here? Organizing Against War and Racism” deal with the issue of minority participation in the antiwar movement. “Not Showing Up: Blacks, Military Recruitment, and the Anti-War Movement” tackles the issue head on. Many antiwar demonstrations are predominantly white, even though Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately affected by the “poverty draft” and the budget cuts to public services that are a corollary to billions spent at war abroad. As author Kenyon Farrow notes, “…Blacks are about 13 percent of the total U.S. population and make up nearly a quarter of all Army enlistees.” Farrow argues for a more nuanced conception of what qualifies as antiwar “resistance” in regards to the African American community. “Activists define resistance in a very narrow way,” writes Kai Lumumba Barrow, a longtime activist and Northeast coordinator for Critical Resistance. Barrow says that while marches, rallies, and sit-ins are the most coherent forms of resistance for many whites, Blacks have also resisted through armed struggle, cultural production, and more subtle tactics.” Furthermore, “the left needs to develop strategies that are cognizant to the barriers to organizing that Black communities face. These include the militarization of Black communities via policing, public housing, and public schools.”

The collection ultimately raises more questions than it does provide answers. But in this moment of reflection and regrouping, this is exactly what antiwar activists will find helpful and edifying.