Continuities: Pushing for Radical Transformation

As War Resisters League organizers, and as people committing our lives to challenging militarism, we don’t often see moments when our work comes together and people power is stronger than people in power. But a lot came together last September 5, when for once we could truly feel that people power strength.

It was a cross-community rally outside of the Oakland Marriott—the host of cop-shop weapons expo Urban Shield, the culmination of months of local and national organizing. Toward the end of the day, we were excited to hear the announcement from Oakland Mayor Jean Quan: Urban Shield would end its eight-year run and not be hosted in Oakland next year.

As organizers celebrated this development, we also under- stood this was just the beginning—not only of our work against Urban Shield, but in forging synergy between movements against war, militarism, and police violence, and for the self-determina- tion of all communities. As the Stop Urban Shield coalition said in our statement the next day:

“Organizers have asserted, however, that their work is far from over. While Oakland will not host the trade show and training, they have not received guarantees that the city will complete- ly withdraw participation, i.e.. providing city funding, sending city agencies and offering city sites for future Urban Shields. In the words of Lara Kiswani of the Arab Resource and Organizing Center, ‘We say no to Urban Shield anywhere; we say no to mili- tarization everywhere.’”

For antiwar activists, saying no to militarization every- where means resisting the obvious, such as armored tanks and drones, but it also means fighting—and transform- ing—a state of mind. Militarized mentalities have permeat- ed U.S. police departments and dramatically amplified the force of police violence affecting a variety of communities. Militarized mentalities have also begun to infuse emergency preparedness as we saw in Oakland and Boston’s Urban Shield expos, where firefighters and EMT train right along with heavily armed SWAT teams, all funded by the Department of Homeland Security. Urban Shield, a private entity despite its DHS funding, doubles as war expo for arms vendors to show off their high-caliber products, while also providing a space for global police departments to play-act counter-terrorism with war weaponry.

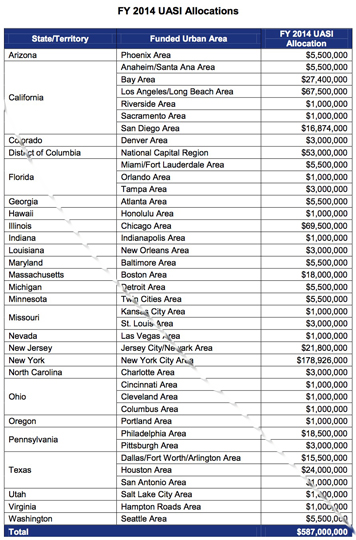

In response, WRL is challenging a significant support structure for this militarization, by striking at the more than half-billion-dollar federal grant program, the UASI—Urban Areas Security Initiative, which strengthens and unifies state repression by funding for “emergency response” in more than 38 “at-risk” urban areas. That the emergency scenarios they train in, and the language they use, are steeped in the “War on Terror” is not an accident.

READYING THE GROUND

The mid-1960s and the ’70s and ’80s saw the introduc- tion of high-level military equipment and techniques to U.S. police forces via the wars on drugs and crime. These early model SWAT teams were upgraded in the following decades under the National Defense Authorization Act, which contained weap- ons transfer programs between the military and police, first for “counter-drug” activities, and later for “counter-terrorism” purposes and the “enhancement of officer safety.” It is in this light that we must understand the “War on Terror” because that is the rationale or with which the Department of Homeland Security continues to further consolidate police and military infrastructure. (One example gaining much notoriety of late due to the Ferguson uprisings is the Pentagon’s 1033 “Excess Property” program, the 1997 extension of the NDAA that allows for the transfer of military arms and equipment from the federal gov- ernment to state and local law enforcement agencies—free of charge.)

The Urban Areas Security Initiative, the billion-dollar grant program under the Department of Homeland Security that subsidizes the transformation of police forces from civilian to quasi-military agencies is another example of how the relation- ships between federal and city institutions have continued to deepen since the Bush administration in the early 2000s. (For more detail on this, see the DHS “Fact Sheet: Office of State and Local Government Coordination & Preparedness,” pbadup- ws.nrc.gov/docs/ML0427/ML042740697.pdf.) UASI, which is perhaps of greater concern than the 1033 program due to the nature and scale of its operations, bankrolls massive trainings in SWAT techniques, helping sequester practice areas in city neighborhoods (rural areas are not necessarily excluded), often without residents’ foreknowledge. Most alarming, it requires all agencies accessing its funds, from fire departments to emer- gency responders, to have a “nexus to terrorism” in all trainings and activities. By calling for increased coordination between law enforcement and emergency management offices, as well as corporate and nonprofit institutions, UASI is, in the words of the New York City Office of Emergency Management, creating a “one-stop-shop.”

This rapid amalgamation of city agencies will only lead to a tighter web of repression used against those already deemed disposable, dangerous, and/or “radical.” We reject a furthering of these cultures of fear. Fostering paranoia and normalizing a constant state of emergency, these UASI allotments, undertaken in the name of security, have incredibly repressive potential, the effects of which we can see every day—if we know where to look.

The road to police militarization in Ferguson was paved in other cities by UASI, among them Oakland and Boston. Both cities have made the news for SWAT activity. One famed moment during Occupy Oakland in 2012 was what NBC News described as the police’s “overwhelmingly military-type response” to the protesters’ encampment. On April 15, 2013, the same day as the Boston Marathon Bombing, armored police indiscriminately raided homes in Dorchester and Roxbury—primarily neighbor- hoods of working-class people of color—arresting 30 individuals on suspicion of selling marijuana, oxycodone pills, and crack cocaine. Perhaps more controversial, both cities have hosted Urban Shield expos.

MAKING THE ROAD

WRL’s current campaign, Demilitarize Health & Security: A Campaign to End the Urban Areas Security Initiative, takes non- violent aim, so to speak, squarely at UASI to challenge milita- rism and lift up community wellness and safety. The campaign is grounded in the conviction that if we dismantle police power internationally, we challenge U.S. militarism locally.

However, this campaign is also rooted in the understanding that across communities, there is a need for solutions to pov- erty, violence, and trauma, and that these very solutions can and will be made by the communities themselves. Through lifting up self-determination and reallocating of resources to allow for community wellness and resilience, we further support imagin- ing a world where we get to decide how to take care of one another, where funding and resources for climate emergencies or family safety don’t come through the Pentagon and police departments, and where communities have the resources and political power to define priorities for public safety and emer- gency preparedness—a world that allows all people the ability to transform violence and empower peace.

The campaign is anchoring three coalitions nationally, starting in the San Francisco Bay Area, Boston, and New York City, and using a diversity of tactics to further build people power against police militarization.

- The Bay Area’s “Stop Urban Shield” Coalition: As described above, after two years of campaigning against the war-expo and SWAT team-training, Urban Shield expo, the Stop Urban Shield cross-community coalition was successful in creating enough local and national pressure so that Oakland’s mayor banned Urban Shield from that city.While this victory is great, the coalition continues to organize together as the arms expo moves to the nearby city of Pleasanton for fall 2015.

- Boston’s “STOMP”: The Boston STOMP coalition, “STop Oppressive Militarized Policing,” was formed around an aware- ness that Urban Shield was also a presence in their town, one that extended the violent logic of policing there and was also very connected to the lockdown of the town of Watertown af- ter the bombing at the 2013 Boston Marathon, and the lock- down’s heavily militarized parades in residential areas that so disturbed the entire country. STOMP had leaders from many movements, including Youth Against Mass Incarceration and Black and Pink. Building on that momentum, the forces of this coalition are gathering for renewed action this spring.

- New York City’s “Demilitarize Health & Security” Coalition: With the largest and wealthiest police department in the country (with offices in 11 cities around the world), as well as vibrant and far-reaching organizing against police violence, New York City is a key site of struggle. Early this year, Police Commissioner Bill Bratton’s announcement of new militarized units, equating protesters with terrorists, only underlines how what used to be Mayor Bloomberg’s army continues to grow. Living in the largest recipient of UASI grant funding (at around $179 million in 2014), New Yorkers are increasingly raising the call to demilitarize. As a recent cross-community state- ment opposing the new NYPD units states:

“We, the undersigned, demand the immediate dismantling of the new NYPD counterterrorism auxiliary unit and Strategic Response Group, which will only deepen the crisis of police violence and repression faced by our communities. Instead of building the NYPD’s power to criminalize, control, and kill people, we need resources that keep communities healthy, whole and free to flourish. We will not stop until we have them!”

Not stopping means knowing where we are going, knowing what world it is that we want, and living that in our practice of resistance. It means transforming what at times seems like the endless repression and fear around us to caring, support, and the beauty of solidarity. It means pushing for something radical we might call revolutionary nonviolence.

For more information on the Demilitarize Health and Security campaign, see www.enduasi.org/p/139/demilitarize-health-security.