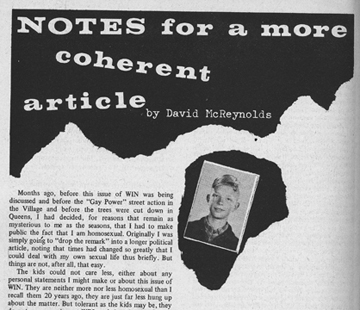

My Favorite Issue: The One on Gay Liberation, 1969

I was asked for this final issue of WIN to comment on the Gay Liberation issue of 1969, which had an article by Paul Goodman and a long one by me (“Notes for a more coherent article”). The irony is that I cannot claim to have been an activist in the Gay Liberation movement, yet this article of mine, and this issue of WIN were important. Let me take readers back to that “homosexual world” as I knew it (and as I had known it since becoming aware in 1949 that I was homosexual).

I would never, in 1969, at the age of 40, have guessed this “deviant world” would morph so radically into what it is now, when I’m 85. I never even liked the term “gay,” as I didn’t, in my experience, find that much about it that was gay. It was a neurotic world, filled with guilt, too much alcoholism, and centered around youth. After 40, one truly entered the dark ages.

Nor am I clear why I wrote the article, what drove me to “come out in print” with one of the very first such articles. While I was certainly influenced by the Stonewall riots, the Stonewall kids were not my crowd. I had tried to go to Stonewall once, some time before the riots, but was turned away at the door. Too old? Too straight? It was a gathering place for young cross-dressing fellows—frankly the last people from whom I would expect a revolution. (But looking back, all power to them!)

Many of us in the gay community went over to the West Village immediately after the first riotous night. I ran into Allen Ginsberg there, observing, as I was. (One of the things about Allen that most deeply impressed me was that he was an openly gay man, at that time almost the only writer or poet in America who was.)

In 1969 there were virtually no openly gay men in public life (and fewer open lesbians, if any). The exceptions proved the rule. Everyone knew Liberace was a bit queer — everyone except his audience of middle-aged women, who adored him. Gay writers such as James Baldwin were not “out.” Major cultural figures, such as composer Leonard Bernstein, had felt it best to get married, so deep was the bias against anyone openly gay. Novelist Truman Capote served as a shield for a host of other gay writers — Capote, so obvious and flamboyant, was what people thought homosexuals were like.

In reality the vast majority of us moved through the world invisible to all except very close friends. What characterized gay life in those days was the need for secrecy. What would our families, our fellow workers, our employers, think if they knew we were queer? Readers of WIN know that civil rights and peace icon Bayard Rustin spent much of his life worrying that his arrest on a morals charge in Pasadena in 1953 would destroy his value to the movement. But it was not just Bayard who suffered. My close friend at UCLA, Alvin Ailey, who would go on to fame as a dancer and choreographer, as a youth spent 30 days in the Los Angeles county jail on a morals charge. My friend Johnnie Labarge was picked up in Ocean Park by the vice squad and spent 30 days in jail. (What a grand party I threw for him when he got out, with everyone from the two gay bars there, the Tropic Village and the Captain’s Inn, turning up at the home of lesbian friends of mine, after the bars closed. I think the great — and today almost unknown — lesbian singer Aggie Dukes joined that party. Who now, reading this, even remembers the Tropic Village or heard Aggie Dukes sing? Johnnie, I fear, is long dead. And I only barely, and by the grace of God, avoided being picked up by the same vice squad agent who arrested Johnnie).

We were all potential felons, immoral creatures, our private lives, our loves, in violation of church and state. None of us then would have believed the time would come when openly lesbian TV stars Ellen DeGeneres and Rachel Maddow would be such accepted figures, or that two of the CNN anchors, Don Lemon and Anderson Cooper, would be openly gay?

We were all potential felons, immoral creatures, our private lives, our loves, in violation of church and state. None of us then would have believed the time would come when openly lesbian TV stars Ellen DeGeneres and Rachel Maddow would be such accepted figures, or that two of the CNN anchors, Don Lemon and Anderson Cooper, would be openly gay?

We would certainly not have believed gay marriage was on anyone’s agenda. That is the great sea change in what is now called the LGBT community, that and the number of same-sex couples who are raising children. I can think of no other change so radical, so unexpected. It may, in part, have occurred because of the AIDS epidemic. The sexual part of gay culture in the sixties was the freedom of the scene, and few were the liaisons that lasted more than a single night or at best a few weeks. That youthful abandon ended with a gener- ation of young men seeing most of their friends die of AIDS. I know that if I were ten years younger I’d be dead — I was just old enough when the frenzy hit that I wasn’t part of it. But even I lost several friends. I remember visiting one in hospital, early in the plague. The room was curtained off, and one had to wear a mask, gown, and gloves before entering, since in those early days no one knew how the disease was transmitted. I think it was this that caused men to look for liaisons that lasted more than a week or so.

What moved me, then, in 1969, to write that article, when silence was the iron rule?

I’m not sure. I was then descending into the personal darkness of alcoholism. Perhaps one part of me thought such an article would gain me some attention. But that is not really fair — Bayard taught me that all of us act from mixed motives. I think the key reason was that I was tired of living a lie. I had visited Bayard in jail after his Pasadena arrest (he was utterly broken by the arrest) and when he got out had him down to my beach shack in Ocean Park for dinner. As I drove him there, I said that one of the reasons I admired him so deeply was that he was the only man I knew who was aware that half of what he said was a lie.

I didn’t mean just the things which, on reflection, are obvious. If you were sheltering Jews in your basement in Germany, and a Gestapo officer asked if you were hiding Jews, you would certainly violate the principle of absolute honesty by saying no. (As Bayard pointed out, “moral absolutes, in the real world, can conflict,” a point Bertolt Brecht — himself no stranger to homosexuality — would have appreciated). No, what I meant was that those of us who were homosexual hid this fact when we spoke of the Gandhian principle of absolute truth. Yes, truth and honesty about everything … except our own lives, which were in violation of the laws, and about which we had to keep silent in order to speak the truth about war and peace, racism, capitalism. Truth about everything… except the one thing that could destroy us.

My article was an effort to be honest at last.

You, reading this now, cannot believe how underground homosexuals were in 1969. If I helped crack open that un- derground, then the article was important and WIN magazine played a crucial rule in publishing it. I did not know, in writing it, what would happen to me—what would be the reaction of the War Resisters League for which I worked. Indeed, when Bayard read the article, he called Ralph DiGia, on the staff at WRL and an old friend, and said, “Ralph, you folks have to get rid of David. He will destroy the league.” I did not feel betrayed by Bayard — one of my personal heroes — because I understood very well the fears that moved him.

But to the credit of WRL (which obviously survived my article), I remained at my post there for many additional years.

David McReynolds joined the staff of Liberation in 1957 and the WRL staff in 1960. He was long involved with WIN and the NVA. He also ran for Congress on the Peace and Freedom Party ticket in 1968, for the New York Senate in 2004 as a Green Party candidate, and for the U.S. Presidency on the Socialist Party ticket in 1980 and 2000. He retired from the WRL staff in 1999. He has never retired from radicalism.