BOOK REVIEW: Day of Honey

The Flavor of Freedom…and War

The Flavor of Freedom…and War

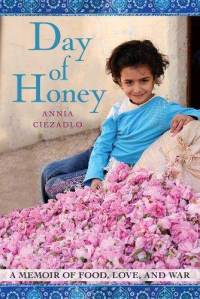

Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love and War

By Annia Ciezadlo

Free Press, 2011, 400 pages, $26

Annia Ciezadlo is a self-described “Polish-Greek-Scotch- Irish mutt from working-class Chicago…who curses like a sailor.” She says she will “eat anything, from tongue to tripe to grilled lamb testicles…a delicacy in Lebanon.”

Mohamad is a Shiite Muslim born in Beirut and then sent to live with family in Jackson Heights, Queens, when he is 10, to escape the civil war in Lebanon. He’s not a talker but Ciezadlo says, “He’ll listen quietly, then eviscerating with one perfect sentence.” The list of foods Mohamed will not eat is lengthy, and his picky eating habits are so notorious that they are his family’s favorite running joke.

Day of Honey: A Memoir of Food, Love and War, Ciezadlo’s first book, is the story of their friendship, their unlikely romance, and eventual marriage. It wends its way through the first five years of their lives together.

The book opens in a moment shortly after September 11, 2001 and a ride to Queens with a cabbie she describes as “an endangered species, among the few white, native-born cab drivers left in New York. Meaty, middle-aged, face like a potato.” He complains to Ciezadlo that all his Arab and Muslim fellow New Yorkers have suddenly become al-Qaeda. She listens and then replies adamantly that her boyfriend is Arab, as are many of her friends, and that none of them are al-Qaeda. This silences the cab driver—never an easy feat. He thinks about it for a moment then gently retreats to a neutral topic: food. “You know that place Sahadi’s?” he says “Y’ever been there? They got great food in there, yeah. Hummus, falafel, you know. Boy, that stuff is pretty good. You ever try it?”

Thus she introduces the complicated themes woven through her memoir: love, food, family, friends, clashes of culture, prejudice, and war’s profound effects on the everyday lives of civilians.

Ciezadlo is enthralled by all aspects of food: preparing it, eating it, sharing it, and researching its provenance. She writes at length about the history of food in the Middle East, home to the oldest known permanent human settlements and the oldest archaeological evidence of cooking. She includes well-researched back stories on, and recipes for, the dishes she comes to cherish most.

When Mohamad is made Mid-East bureau chief at his job for the local daily paper, Newsday, his first assignment is covering the war in Iraq. They decide to marry and, after spending some time in Beirut with Mohamed’s family, they embark for Baghdad on a working honeymoon as war correspondents.

Ciezadlo’s first eating experiences in Iraq consist of disastrous, ill-prepared hotel food, which only make her determined to uncover the real food story of Iraq. She begins by asking people she meets to recommend dishes. Everyone tells her the same thing: She needs to try masquf, a kind of carp called a barbel that is fished from the Tigris River and then slow roasted for one hour over a wood fire.

The Iraqis she meets equate the dish with a time when people would gather in cafes and restaurants along the Tigris in the evenings, before Saddam Hussein and before the U.S. occupation. “There is a phrase Iraqis were always using: the flavor of freedom. For a lot of Baghdadis, that flavor was masquf. It was more than just a fish, or a way of preparing it; the ritual of masquf embodied a vanished place and time and way of life.” The fate of this dish and its place in the Iraqi memory served as a primer for understanding what decades of repression and war had cost the Iraqi people.

Her time in Iraq and Lebanon is spent collecting people, stories, and foods. Her perspective is focused on how people cope with the erosion of freedom and safety and strive to keep living their lives. One of her first stories is not about car bombs or troop movements but about an Iraqi family driving around war-torn Baghdad in search of a birthday cake for their young daughter. She never editorializes, but her anger and frustration when describing the fates suffered by her friends in the war zones is palpable.

During the height of the Israeli bombing of South Lebanon, she describes the government going into its “crisis plan”—in other words, shutting down—and leaving thousands of internally displaced civilians without help. The role of attending to people fleeing the South and destroyed parts of Beirut is taken up by an ad hoc assortment of individuals and civic groups. Medical students offer free basic health care to refugees crowded into Beirut’s few open spaces. Local cafe owners keep their doors open day and night to shelter and feed their neighbors.

When the Israeli bombing gives way to sectarian militia violence in the streets of Beirut, some merchants brave the worst of it to remain open, serving their neighborhoods. One merchant she knows, a local ghanouj (cheese maker), stays open selling cheese during particularly heavy fighting. She asks him why people would pick that moment, during a firefight, to decide they must have cheese. The merchant smiles and answers, “Because they think they will never be able to taste it again.”

The book is shocking and sad in places yet riotously funny in others. Ciezadlo’s description of the transformation she undergoes when wearing a hijab is second only to the vaudeville-worthy exchanges with her mother-in-law, Umm Hassane, as Ciezadlo learns to cook Lebanese food. An early lesson involves making Batata wa Bayd, a dish of onions, potatoes, and eggs where timing and the order of ingredients is everything. Yet when she asks Umm Hassane how long the potatoes should cook with the onions before adding the eggs, her mother-in-law answers, visibly annoyed, “Until they are ready!”

In the end, Annia Ciezadlo has brought to the reader a funny, intelligent book about food as a guide to navigating the complexities of relationships and culture in good times and in bad. She has also written something very unique, a detailed account of the lives of everyday people coping in war zones.