Artist-Activist Partnerships: Five Tips for Booking Your Benefit

There has always been an important relationship between social movements and the arts. Artists frame political ideas in concrete and engaging ways. They use their networks to publicize and strengthen campaigns. When artists and activists work together in an organic, intentional, mutually beneficial way, they have the power to turn social movements into social/cultural movements—to change not just circumstances but hearts and minds as well.

But that “organic, intentional, mutually beneficial” partnership isn’t always easy to build. With Occupy protests around the country and thousands of other causes, campaigns, and movements around the globe, it’s more important than ever that artists and organizers get on the same page. What follows are five tips and ideas for building a powerful activist-artist alliance.

1. Artists Have Skills

Too often, activists look to artists only when it’s time for a fundraiser or benefit show, or when they need a musical break between speakers at a rally. But many artists have a lot more to offer. For example, some artists have experience with effective stage management, setting up events to be engaging and dynamic from start to finish (as opposed to a dozen speakers all saying the same thing). Artists have promotion and outreach tools, from managing email lists to engaging in effective Twitter/Facebook campaigns. Artists might know how to run the soundboard better than the person who rented it. Artists may know how to tap into communities beyond the “usual suspects” who already show up to every rally.

Rather than simply meeting the artist at the event and saying “thanks” when it’s over, set up a meeting with the artist a week or two beforehand. Explore ideas. Share skills. We all have a lot we can learn from one another.

2. Synergy is Better than Altruism

Even though you may know a bunch of talented, committed artist/activists who are down to collaborate on every event, make sure you’re not always asking these people to help out of the goodness of their hearts. Work to create scenarios where everybody wins because that’s going to be more sustainable.

Artists collaborating with an activist campaign are already getting something out of it: exposure to a new audience, an opportunity to perform in front of a big crowd (potentially), their names on the flyer, etc. But we can go beyond this. Whenever possible, pay the artists. When that isn’t an option (because you’re trying to raise money or the artist is refusing the payment), think of more creative ways: Send out that artist’s web address to your email list. Post that artist’s page on your organization’s Facebook wall with an adoring note. Most important, offer to do all this before the artist has agreed to work with you. Be intentional about collaboration.

And maybe this goes without saying, but be nice to the artist, too. Be organized. Have a sound system that works. Be polite and gracious.

3. Promotion is a Shared Responsibility

Activists should never assume that an artist—no matter how well known—will automatically draw an audience. On the flip-side, artists should not assume that every activist event is going to be a huge party where all they have to do is show up and perform. Both parties need to be responsible for promotion.

When we all work together (through flyers, Facebook, Twitter, email lists, posters, community outreach, etc.), we can create huge, vibrant, diverse events. When we think we don’t have to help promote, nobody shows up. Artists do generally have promotional networks—lots of followers, big email lists, etc. They cannot, however, be expected to use them unless they’re explicitly asked to. Again, we have to be intentional about promotion. Everyone involved in an event should sit down a few weeks before and create a solid plan.

4. It’s About the Community

As much as I want to shout out my friends who create art that is social justice-oriented, sometimes organizers focus too much on these “conscious” artists and forget that the content of the work isn’t necessarily what’s important. What really matters is getting people in the room together. Sometimes a DJ who can rock a party is more valuable than a folk singer who has lots of songs about economic injustice. It depends on the event and the role of the artist at that event.

Reaching beyond the artists who “make sense” in an activist context can also bring new people into the fold. Maybe your city has a popular indie rock band or an MC who is talented but not all that political. Reaching out to them might be the first step in reaching out to their fan communities. I’m not saying we should ignore or stop working with the artists who work with political content, just that we can be more creative when generating lineups.

5. Be Intentional About Everything

As powerful as an artist-activist alliance can be, it only works when it’s organized intentionally. I encourage artists to get involved in the groundwork of activist movements, rather than just

supporting through performances or the occasional “tweet.” By the same token, activists should be thoroughly involved in their communities’ arts scenes. If we want to organize our communities and neighborhoods, we have to exist in them genuinely.

The best experiences of my career have involved collaborating with activist causes and events. I’ve been privileged to see firsthand the power this sort of collaboration can have when it’s done right. When we talk about taking our activism to the next level, we have to be talking about the arts. When we talk about reaching beyond the usual college-educated white radical audience, we have to be talking about the arts. And when we talk about building a truly mass movement that can challenge the oppressive institutions we’re up against, the arts have to be part of that strategy.

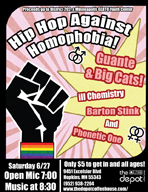

Hip Hop Against Homophobia: A Case Study in Collaboration

The Twin Cities have one of the deepest, most distinctive, and most talented independent hip hop scenes in the country. You might not expect it, but with underground rap juggernauts like Atmosphere, Brother Ali, and Doomtree; boundary-pushing avant-gardists like Kristoff Krane, no Bird Sing, and Kill the Vultures; and meat-and-potatoes lyrical hip hop like Toki Wright, muja messiah, Big Quarters, and Ill Chemistry, Minnesota is definitely a healthy breeding ground for hip hop.

The Twin Cities are also home to one of the strongest, most organized LGBTQ communities in the nation. The Advocate called Minneapolis “The Gayest City in America,” saying, “over the past decade, Minneapolis has become the gay magnet city of the midwest. It makes sense: People here are no-nonsense, practical, and don’t deal well with hypocrites.” There are a ton of strong organizations and popular regular events that cater to and celebrate LGBTQ identities.

As both a hip hop artist and a social justice activist/educator, I’ve always been interested in the overlap between communities and cultures. In this particular case, we have two communities that overlap—plenty of LGTBQ-identified Twin Citians love hip hop, and a handful of local artists identify as lGBTQ. That’s great. But what caught my eye when I moved here in 2007 was the potential for a powerful, ground-shaking collaboration between two big, beautiful, diverse communities.

That’s what Hip Hop Against Homophobia (HHAH) is trying to promote. In 2008, I worked with local activist Jessica Rosenberg to throw the first HHAH event, a concert at a Minneapolis bar called the Nomad. The response was huge; it sold out soon after doors opened, and many people had to be turned away. We raised more than $1,000 for LGBTQ activist causes, but most important, we got a ton of media coverage and set the stage for more.

Since that first show, we’ve had eight more successful installments in the Twin Cities and surrounding communities, featuring both LGBTQ-identified artists and straight allies, artists like Toki Wright, Maria Isa, Heidi Barton Stink, Kaoz, Mike Mictlan of Doomtree, Desdamona & Carnage, Kredentials, See More Perspective, Tori Fixx, Tish Jones, and many more (including myself). Plans are in place to take the show on the road this year, reaching out to smaller minnesota communities, particularly those that don’t have as many resources as the Twin Cities.

The purpose of this concert series is ever-evolving and flexible. Sometimes it’s about raising money for a particular cause or campaign. Sometimes it’s just about throwing a good party. Whatever the function of the individual show, the broader purpose is create space for dialogue around the issue of homophobia in hip hop culture, space for LGBTQ individuals and allies to go to a rap show and listen to something beyond “guilty pleasures,” space for the acknowledgment that these two communities overlap a lot more than we may think, and that working together, we can make that overlap even bigger.

Please, by all means, steal this idea. Do it in your city. on the logistical end, there are a few suggestions. Get a good DJ. Find a venue with gender-neutral restrooms (or change signage accordingly). When forming the lineups, mix it up between LGBTQ artists and straight allies; often (though not always), those allies have larger followings composed of people who may not have thought much about LGBTQ justice. Just seeing a particular rapper’s name on the bill can be a powerful statement that has ripple effects. We’ve also tried to keep the bills representative in terms of other identities—all white rappers, for example, isn’t a good idea (though it happens here in the midwest more often than you might guess). Finding performers of varied gender identities is ideal. You can also keep it diverse in terms of musical style—not all hip hop is the same, after all.

Perhaps most important, we’ve tried to be intentional about promotion. even if only 100 people come to the show, 10,000 might read about it, see a flyer, or get a Facebook invite. Just the name “Hip Hop Against Homophobia” can start conversations and get people thinking. So work together—promoters, artists, fans, organizations, and everyone involved—pool your networking power and get your community engaged and excited.

Because in the end, that’s really what HHAH is about. It could just as easily be “Folk Rockers Against Racism” or “Slam Poets for Universal Health Care” or “Trip Hop Against Police Brutality.” This is about collaboration and building community. While artist/activists can sometimes get too event-focused, events can still be gateways to deeper, more intentional work.

A concert by itself can’t change the world. But the people who go to that concert, meet one another, have conversations, and keep building beyond that night definitely can.