People’s Poetry: Rap Music in Social Justice Curriculum

“The revolution’s here, the revolution is personal.”

—Talib Kweli, “Beautiful Struggle”

I have a wonderful, multidimensional trade.

As a Vermont English teacher, I am accountable to the State of Vermont for designing curriculum and assessing students using state standards. For example, a lesson plan might be guided by an objective like “5.11 Literary Elements and Devices: Students use literary elements and devices—including theme, plot, style, and metaphor—to analyze, compare, interpret, and create literature.”

As a social justice educator, an activist, and a person who sees education as a path for humanizing the world, for liberation in the Freirian sense, I ground my lessons in questions about racism, class, inequality, and resistance. The questions I ask are designed to help students and me critically examine the way society is organized, whether we wish to change the conditions of the world and our communities, and how we are going to do it.

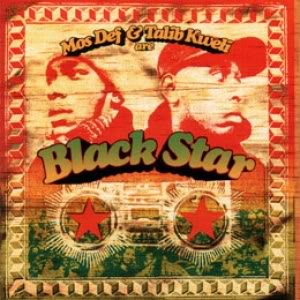

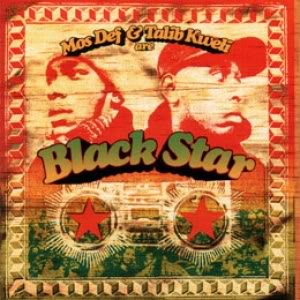

When teaching literature, I use materials that center around the experiences of poor and working people, people of color, women, LGBTQ folks, and others who remain on the margins of the “Shakespeare Canon.” It was on this basis that I selected as a text Black Star, Mos Def and Talib Kweli’s legendary album, released in 1998. I had been itching to do something that educators have been doing for decades: teaching rap songs as texts in the classroom. For students of color in urban communities, a lot of the material rings relevant and real. What does it mean to teach rap in semi-rural, predominantly white settings?

The Context

I am an instructor at a program in Vermont for public school students who are transitioning between the mainstream school and alternative placements. Sometimes students are in the program for several days while awaiting placement elsewhere; other times, students are with us for multiple semesters. The numbers at this small program are both a blessing and a challenge: I never have more than three students in the classroom at a time. I work with high school students with a wide range of literacy and ability to be present for learning. All students in the program at this moment are white, and they have varied experiences of class, gender, sexuality, and ability.

The Lesson

One Black Star song we are focusing on during this mini-unit on figurative language (metaphor, simile, alliteration, etc.) is “Astronomy (8th Light).” I chose this track for the multitude of similes used to describe what it means to be a “black star,” a symbol of beauty, history, and struggle. Lyrics like “Blacker than my granddaddy’s armchair/He never really got no time to chill there/’cause his life was warfare” give the listener a visual image that, when we look closely, points to the experience of a black man during a particular period of time.

Questions that we might discuss or write about include:

• Why, historically, might life have been difficult for a black man the age of Mos Def’s or Talib Kweli’s grandfather?

• What “warfare” might the rappers be referring to?

• What were conditions like for people of color in the first part of the 20th century? Why?

• What are the barriers that people of color face today?

The lyric “Black like the perception of who on welfare” provides another avenue for a critical conversation about “welfare” — about wealth, income, inequality, history, and racism.

Questions:

Questions:

- Why do people perceive that it’s black folks who are on welfare?

- Who is actually on welfare?

- What do we know about the welfare system?

- Do we believe that the government should provide a safety net?

- What’s the history of welfare in the United States?

And, of course, there’s tying the lyrics into students’ lived experiences:

- What are your perceptions of welfare?

- Where do those ideas come from?

- Do those ideas match up with your own experience?

- What social and economic supports do people in our community have if they lose a job or a home?

In the six months prior to this lesson, our town was struck by both a fire that devastated a significant portion of downtown and the rushing waters of Tropical Storm Irene. Both events destroyed housing for hundreds of community members; many who were already living precariously were pushed to rely primarily on the support of the state and their neighbors. Students connect this local situation to the content of the song.

After we look at the lyrics while listening to the songs, identify the figurative language, and discuss the content, students are encouraged to write about their own experiences using figurative language.

Talking Race and Racism

Like any other medium that features the political voices of people of color, rap in a classroom will — and should — bring up conversations about race, the kinds of conversations that educators must be poised to facilitate. In order to do this, it was important for me to be clear on my own understanding of and stance on race and racism. For instance, I believe that, in the United States, race and racism have been used to divide working people for the benefit of a small number of people who control a lot. I believe that racism manifests in ways both subtle and glaring: who gets pulled over while driving, who gets harsher prison sentences, who can live in which neighborhoods, and who gets called back to a job interview. I believe I benefit from racism. I believe that it is my job as a white person to organize with other whites and people of color to end racism.

With this unit, as with all others, it was essential for me to know who was in the room. As with conversations that might arise about class and economic inequality (e.g., students’ personal

experiences with being poor while discussing welfare), it is important to facilitate critical conversations about race where students are able to share their ideas honestly. However, it is my job as a social justice educator to know which side I’m on. To be an educator is not to be a neutral referee. I must ask questions and point to ideas that support and celebrate the struggles of

oppressed people.

Knowing this, I was not caught off-guard when “the conversation” came up that is not specific to listening to rap music (for instance, reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn). After

listening to a Black Star song with the word “niggaz,” a student asked, “Why is it ok for black people to use the ‘n-word’ but not white people?” Looking back, I wish I had been prepared with

some historical materials, articles, etc. offering perspectives on that issue from sources other than myself. Since I didn’t have those materials, after the students discussed their differing perspectives, I shared my understanding that the word has been used by whites in collusion with the powerful, violent institutions of chattel slavery, Jim Crow Laws, and other kinds of exploitation and oppression, to the great harm of people of color; until our society is not racist, that word used by a white person will have a harmful power as it reinforces racist power relations. I told students that while I don’t censor the word as it appears in a text that we’re looking at, I personally do not use the word in conversation. A student was disdainful about my “PC” approach; another student said they were willing to be PC if it meant not saying terrible things.

What Next?

I hope that using rap to teach students in a predominantly white classroom will validate rap as a righteous form of expression; students who already like rap can be encouraged to enjoy it more deeply and create some of their own.

In addition, students who start off this unit with groans can, if we’re lucky, get a wider, more nuanced perception of what rap is. Indeed, as with almost any other genre of music, lots of rap is commercialized, misogynistic, materialistic. Nevertheless, the hip hop movement has a rich legacy of revolutionary, socially conscious rappers, emcees, and producers. Luckily for us, no matter what texts we are studying, we can challenge ourselves to put social justice questions at the core of our curriculum.