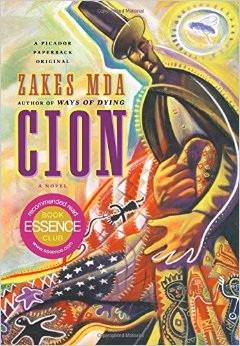

Cion

Life Among the (not-Quite) Native Ohioans

Cion

by Zakes Mda

Picador, 2007,

320 pages, $14

In his first novel Ways of Dying, Zakes Mda introduced readers to Toloki, a poor man living in an unnamed South African city who decides to take up mourning professionally. In exchange for coins, Toloki wanders from one funeral to the next, grieving for those who were lost during the country’s bloody transition from apartheid to democracy.

When we meet him again in Cion, Mda’s strange yet beguiling new novel, Toloki finds himself stranded in a country at its own unique political moment: He is in small-town USA on the eve of the 2004 presidential election. To be precise, it’s Halloween, and Toloki is making his way through a roiling street parade in the college town of Athens, Ohio. it is unclear – and unimportant – what Toloki is doing there (though it’s worth mentioning that Mda currently teaches at Ohio University).

The Halloween parade is full of period detail. The Billionaires for Bush are gallivanting around in their sardonic faux affluence. There’s a group of “three little people in green suites and white fedoras” who carry violin cases like gangsters – the Halliburtons – who trail a man in a Dick Cheney costume. Out of this politically charged atmosphere, Toloki meets a young African-American man dressed in rags. As police drag the man off on a charge of groping a female reveler, he tells Toloki that his name is Nicodemus and that he is a runaway slave.

Really, his name is Obed Quigley, and he is a brash, scheming troublemaker from the nearby hamlet of Kilvert. After Toloki bails him out, Obed invites him to stay with his family. Like most Kilverters, the Quigleys are descendants of a tangled family tree that includes fugitive slaves, Native Americans, and white settlers. They straddle the poverty line, wear donated clothes, and eat donated food from a place called “The Center.” The folks of Kilvert grow vegetables in their backyard for canning and pickling and do things the old-fashioned way. Woven through the story of Toloki’s year-long stay with the quirky Quigley clan is the story of Nicodemus and Abednego, two brothers who escape from a slave-breeding farm in Virginina toward the Ohio River and freedom. It doesn’t take long to realize that this distant memory of the Underground Railroad is on a crash course with the Quigley family.

As the title (an alternate spelling of “scion”) suggests, tradition – a sense of one’s personal lineage – is the specter haunting the novel. in Mda’s configuring, tradition makes us who we are at the same time that it has the potential to keep us from being what we might become. This double-edged conception of cultural conservation – especially as typified by the matriarch Ruth and her fanatical loyalty to making quilts the way her ancestors made them and eating food her ancestors ate and destroying the innovative designs of her fragile daughter – suggests that tradition can be a kind of slavery in itself.

This notion of the burden of tradition should strike anyone familiar with postcolonial African literature and politics as a persistent theme. To Mda’s credit though, no heavy-handed racial ideology – not even the musty brand of Pan-Africanism that one might expect to find in a book about an African man living with rural U.S. Blacks – intrudes on the central story of the Quigley family. On the other hand, when unpacking how this story fits into the larger fabric of contemporary American life, Mda is out of his depth. One imagines he had a checklist of hot-button issues he hoped to address, peppering throughout a series of dull, ineffectual asides referencing Hurricane Katrina, televangelists, the 2004 tsunamis, etc.

Much of the social criticism and analysis will not come as news to many Americans. The often crushing didacticism leads one to believe that Mda’s problem is mainly one of audience. When his narrator engages in tedious recitations of the history of the Republican Party or on the importance of quilts in African-American culture, Mda is not revealing America to itself, like the great tourist-observers of American life (Alexis de Toqueville and Jean Baudrillard come to mind). Instead, like any decent travel writer, he seems to be parsing our tormented, schizophrenic nation for readers in South Africa. In this way Cion is unique, because it essentially reverses the typical travelogue: It’s not about some American sealing a volcano on an exotic island in the South Pacific, but about an African man in exotic rural America.

Recently Barack Obama’s campaign joked about the discovery that pegged Dick Cheney as his distant, ancestral cousin, calling the humorless VP the “black sheep” of the presidential candidate’s family. That the two politicians – who couldn’t seem to have anything less in common – might have some genetic connection is the kind of coincidence that Toloki might have found highly fascinating, but one that might make others shrug and smirk. Unfortunately, one does too much of that while reading Cion.