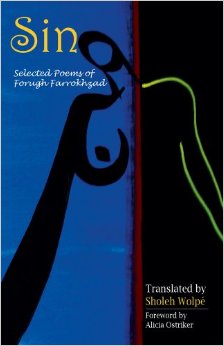

Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrakhzad

Come with me to that star… where no one is afraid of the light

Sin: Selected Poems of Forugh Farrakhzad

Translation by Sholeh Wolpe

University of Arkansas Press, 2007

160 pages, $22.95

And here I am,

a lonely woman

on the threshold of a cold season

at the dawn of realizing earth’s sullied existence

and the sky’s blue despair…

It isn’t easy to do a short review of the work of this female poet writing in Iran in the 1950s, one who used her craft to fashion not just new content but new form, while challenging the poetic establishment and social mores, resisting attempts to confine her to the space allotted by the patriarchal order, and insisting on speaking about her own experiences, her own subjectivity, and — perhaps most transgressively — her own body.

Patriarchy has operated on a double register in the world of poetry (in Iran and elsewhere): virtuosity in verse has been considered a male purview, with women poets operating at the margins of the mainstream. The assumption of the poet-as-male (and consequently the reader-as-male) has resulted in the depiction of women as variously an abstraction, the embodiment of beauty and virtue, the object of desire, or the weak victim awaiting rescue.

In this milieu, the emergence of a poet who inverted this structure by deploying an autobiographical voice to speak of a woman’s desires, passions, and sexual experiences was quite quite extraordinary. Over the course of a brief but blazing life, Farrokhzad published four collections of poetry — beginning with Asir (Captive, 1955) — before she died in a car accident at the age of 32. During this period, she underwent a transformation from being an object of curiosity, to being considered a good “poetess,” to achieving the status of a great “poet.” A fifth volume, Iman Biyavarem beh Aaghaz-e Fasleh Sard (Let Us Believe in the Dawn of the Cold Season), appeared posthumously in 1974. She also made the highly regarded 1962 film Khaneh siah ast (The House is Black).

Farrokhzad’s poems exhibit a wide range of emotions and deal with a variety of concerns, but in most of them her location as a woman embedded within the social system of her time is central. She’s often labeled a pioneering “feminist” poet of Iran, a distinction she both accepted as a meaningful way to look at her work and rejected as an attempt to compartmentalized her and judge her by a narrow standard. In the poem “Sin,” she unabashedy celebrates herself as a liberated sexual being, unrestrained by societal or relgious strictures (“I have sinned a rapturous sin beside a body quivering and spent I do not know what I did O God, in the quiet vacant dark”). “The Wind-Up Doll” is a manifesto of sorts, urging women to examine their condition within the dominant order (“Like a wind-up doll one can look out at the world through glass eyes”).

“Only Voice Remains” echoes the question “Why should I stop?” like a chant, asserting her right to speak (“my heart’s charter cannot be drafted by the provincial government of the blind”). It ends wiht words that Farrokhzad must surely be directing at her critics: “It’s the flower’d bloodstained history that has committed me to life, the flower’s bloodstained history, you hear?”

Sholeh Wolpe’s translations of these Persian poems are done with a sure hand, though her insitence on emphasizing the poetic over the literal inserts the translator’s voice into the verse more strongly than in some other attempts at rendering Farrokhzad in English. But then, one has to pick one’s poison when embarking on the perilous journey of translating.

Farrokhzad’s work — in this book and elsewhere — is well worth reading (City Lights Books’ forthcoming If I Were God, translated by Meetra A. Sofia, will join Wolpe’s Sin as the only widely available English volumes). Her writing — scandalous by the standards of her times — was a much-needed slap in the face of public taste. Its verisimilitude is startling, its courage unmistakeable, and its assertion of Farrokhzas’s right to her emotions, her body, and her voice, particularly at a time when art, music, film and literature from the “Axis of Evil” might help corrupt our all too expedient representations of complex “civilizations” and fluid histories.