Women Resist Behind Bars

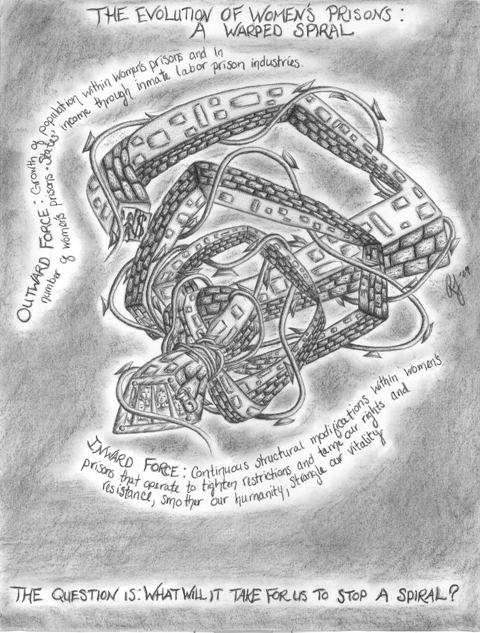

Illustrations by Rachel Galindo

Women have resisted and protested their conditions of confinement since the start of separate female prisons in the 1800s. However, despite the growing body of literature examining female incarceration, little attention has been paid to what women do to change or protest their conditions, thus reinforcing prevailing stereotypes of women as passive victims and the belief that incarcerated women do not organize. Researchers, scholars, and activists continue to focus on the causes, conditions, and effects of women’s incarceration while ignoring the women’s attempts to change or protest these circumstances.

This lack of attention has led to not only an absence of literature but a lack of outside support and resources for and about their issues and actions. Instead of claiming that women in prison do not engage in riots and protest actions that capture media attention, scholars, researchers, and activists should examine why women’s acts of organizing and resistance fail to attract the same public attention and support as those of incarcerated men.

Growing Numbers

The number of women in federal and state prisons has grown twenty fold in the last 40 years, from 5,600 in 1970 to 115,308 by the middle of 2007. What caused this explosion in women’s incarceration?

From President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “war on crime” in 1965 to Washington State’s “three strikes” legislation in 1993 (which mandates life in prison without the possibility of parole for a third conviction), the policy has increasingly been to blame street crime for the nation’s growing civil unrest.

A preoccupation with drug use contributed greatly as well. President Ronald Reagan’s well-known “war on drugs” expanded both policing and imprisonment. In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act with mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. The act led to a huge expansion in the number of people incarcerated for drug law offenses, from 16,340 in 1986 to 58,260 at the end of 1994.

In addition, the act allowed police and prosecutors to arrest and charge spouses and partners with conspiracy because they took a phone message or signed for a package. Lacking knowledge about drug transactions, spouses and partners are unable to plea-bargain, trading information for a lesser charge. Between 1986 and 1996, the number of women in federal prisons for drug law violations increased 421 percent.

The system affects women of color disproportionately. Bureau of Justice statistics show that 358 of every 100,000 Black women, 152 of every 100,000 Latinas, and 94 of every 100,000 white women are in prison. Racial profiling, not an increase in crime among people of color, accounts for much of this overrepresentation: Policing policies disproportionately target inner-city African-American and Latino neighborhoods. Within the past decade, many police departments have increased the use of stop-and-frisk tactics, in which officers stop, question, and pat down those they perceive as acting suspiciously, often people of color.

Also, alternatives to incarceration are less likely to be offered to people of color: A California study showed that two-thirds of drug treatment slots went to white people despite the fact that 70 percent of people with drug sentences were African-American.

Incarcerated women come from the bottom of the economic ladder: Only 40 percent of all incarcerated women were employed full time before incarceration. Of those, most held low-paying jobs: A study of women under supervision (prison, jail, parole, or probation) found that two-thirds had never held a job that paid more than $6.50 per hour. Approximately 30 percent had been receiving public assistance before being arrested. The 1996 welfare reform disqualified those with drug felonies and probation or parole violations. Between 1996 and 1999, more than 96,000 women were subject to the welfare ban because of past drug convictions.

HIV Organizing in Prison

The majority of women enter prison after years of poverty, poor nutrition, substance abuse, and a lack of access to health care. In addition, these women have fewer resources and options for survival than women in higher economic brackets and are often forced to engage in riskier activity, making them more susceptible to diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C. Women in prison are more likely to be HIV-positive than either men in prison or women on the outside. However, prisons have been slow, at best, to respond to the needs of prisoners with HIV and AIDS. Prison conditions exacerbate existing health conditions, and the inadequate medical care can be life threatening for those with serious health problems.

In 1987, women at New York’s Bedford Hills Correctional Facility began the AIDS Counseling and Education program (ACE), a peer education program that cares for women who have HIV/AIDS and combats the fear, ignorance, and stigma around the disease. At the time, prisoners circulated petitions demanding that women who were perceived to have HIV be removed from their housing units. They also ostracized them socially, refusing to share meals or have physical contact with them. Staff members, including medical staff, also knew little about the disease and were afraid to have physical contact with their patients. In one horrifying instance, a woman died alone in the intensive care unit because no nurse or guard was willing to attend to her.

ACE members helped women prepare for their medical exams, working with them to define and articulate their questions. In some instances, they also accompanied women to their medical consultations. In addition, ACE battled stereotypes and fears around the disease. They presented educational seminars, often using role-playing to break through barriers, generate discussion, and examine the issues.

ACE continues today, and its model is spreading to other prisons. In 1991, women at the federal prison in Pleasanton, Calif., started the Pleasanton AIDS Counseling and Education (PLACE) program. When the program started, the prison had no pre- or post-testing counseling, no mention of AIDS at orientation for new prisoners, no special diets or vitamins for HIV-positive prisoners, and no treatments besides AZT, an antiretroviral drug that, when administered alone, enabled HIV to develop a resistance to the drug so that it only inhibited the virus for a short time. In addition, AZT was often administered in overly high doses, causing life-threatening side effects.

PLACE members began by educating themselves about the disease and presenting their newfound knowledge to others. The process not only increased awareness about the disease but also combated the sense of powerlessness and the infantilizing manner that incarcerated women face on a daily basis. “The small steps of learning new information and presenting it to a group, or of figuring out goals and a program of AIDS education for our sister prisoners, are really giant steps in the process of empowerment, commitment, and enhancing our self-esteem,” recounted founder Linda Evans.

Even prison administrators are recognizing the value of peer education programs. Oklahoma’s Mabel Bassett Correctional Center instituted an HIV peer education program. In 2007, peer educator Jerrye Broomhall reported, “The level of ignorance is shocking. Stuff like, ‘I don’t want to wash my clothes after her; what if her panties were bloody?’ People don’t want to share cells, meals, so most women just keep their status a secret.” Two years later, Broomhall reported, “I have seen less ignorance. I have heard people refer to what they have learned in class. Women have said they will teach their children, friends, and family things they have learned in class.”

Abuse and Battering

More than half the women in state prisons and local jails report having been physically and/or sexually abused in the past. The Bureau of Justice found that women were three times more likely than men to have been physically or sexually abused prior to incarceration. The prison environment, with its male guards, lack of privacy, physical and verbal abuse, and fear, often perpetuates the abuse. Despite these circumstances, women have connected with and supported each other in their efforts to overcome past trauma.

In the late 1980s, women serving life sentences in Marysville, Ohio, formed a support group called Looking Inward for Excellence (LIFE). Members realized that many had been sentenced to life imprisonment for killing their abusers. At a time when abuse and battering were still not widely recognized in either the courtrooms or outside society, they began working around issues of domestic violence.

LIFE members reached out to other survivors, helping them overcome denial and encouraging them to apply for clemency. Their actions challenged the way prisons normally divide—and breed mistrust among—the people inside: “When you’re in the institution, you get to be kind of secret,” recalled one LIFE member. “But as we started to get information, we would put packets of stuff together, illegally Xerox stuff, and kind of under the cover [say], ‘Read this, you know, this is good reading.’” Their efforts led to 18 additional women applying for clemency.

In the end, 25 women were granted clemency.

The actions of LIFE inspired women at the California Institution for Women to organize a clemency drive. Members of Convicted Women Against Abuse (CWAA), a prisoner-initiated support group for battered women, wrote a letter to then-Governor Pete Wilson asking him to consider commuting their sentences and inviting him to one of their weekly meetings so that he could understand how they had ended up in prison. Wilson declined the invitation, but their letter drew the attention of lawyers and advocates who helped the women draft arguments and gather evidence for clemency petitions.

Wilson granted clemency to three, denied it to seven, and made no decision on 24 of the petitions.

CWAA members continue to meet and share current news regarding domestic violence, homicide cases, court rulings, and their own experiences with the justice system. They also discuss possible legal strategies, media stories about women who fight back, and journalists with a focus on domestic violence.

In both Ohio and California, battered women’s efforts not only strengthened and expanded the clemency processes but also raised public awareness about abuse. Even those who were not granted clemency became empowered to speak out about their experiences instead of continuing to live in shame. The advocates and lawyers who originally helped women with their petitions formed the California Coalition for Battered Women in Prison to continue organizing and educating the public. More than 15 years later, the group, now called Free Battered Women, continues to advocate the release of women imprisoned for self-defense, and its work has helped free 35 women within the past 12 years.

The Need for Outside Support

In the 1970s, off our backs and other radical feminist publications not only reported on the struggles of incarcerated women but connected their fights with those on the outside, urging readers to get involved. Radical feminists formed support groups for imprisoned women and organized campaigns around their issues. In one instance, they managed to generate enough public and political pressure to shut down the Alternative Program Unit (a closed-custody behavior modification unit for women who were deemed “disruptive”—a label that included lesbians, leaders, or the disobedient) at the California Institute for Women.

Today, Arizona prisons have more than 600 cages where prisoners are placed to restrict their movement or while they await medical appointments or work, education, or treatment programs. Although prison policy prohibits using the cages as punishment, lesbians, targeted solely for their sexual orientation, are often placed in these cages, sometimes for hours at a time in over 100-degree weather.

Lesbians are not the only prisoners to suffer in these cages. On May 20, 2009, Marcia Powell, a mentally ill 48-year-old incarcerated in Perryville, died after being left in an unshaded cage for nearly four hours in 107-degree heat. Two-and-a-half weeks later, three women at the same prison simultaneously set fire to their mattresses in an attempt to draw outside attention. However, the lack of connections with outside supporters meant that little attention was paid to their action and they quietly disappeared.

Feminist and other activist groups of the 1970s recognized the importance of reaching out to and including prisoners in the dialogue around social justice. Now, when the prison population is more than 2 million, why aren’t we recognizing how our struggles intersect?

As Rachel Galindo, a woman incarcerated in Colorado, put it:

I was thinking about how we prisoners are very cut off from much of the rest of the world, including people who do not support the prison system or people who may be interested in our struggle. So I think that more communication via letters would help. … The communication between two humans concerning their hopes, ideas, and their plights is what allows them to bond in resistance against a system that affects everyone in many different ways. We prisoners would be inspired to see another position of struggle and that, though they may differ, all struggles are shared. This would strengthen resistance both inside and outside of the prison gates.