WRL History

Click here to read about our 100th Anniversary History Projects

WRL’s Journey from “Wars Will Cease When Men Refuse to Fight” to “Revolutionary Nonviolence”

By Matt Meyer and Judith Mahoney Pasternak

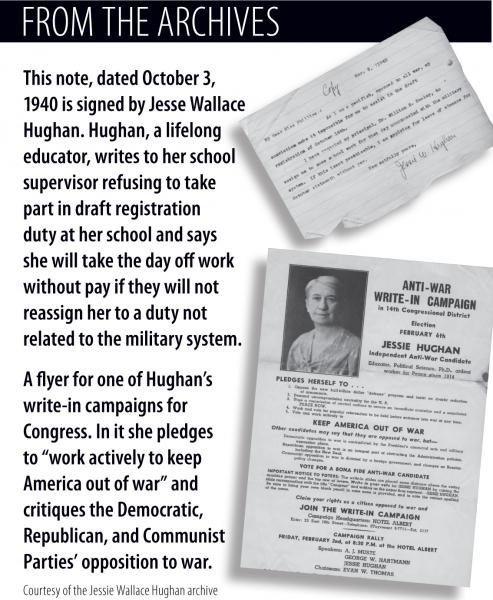

In her diary on October 19, 1923, the 48-year-old New York City educator Jessie Wallace Hughan (1875-1955) wrote, “Tracy [Mygatt] to dinner—had hair done—organized real War Resisters League …”

Hughan was describing the formal founding of WRL as the successor organization to the Anti-Enlistment League, which had opposed armed forces enlistment during World War I. Conscientious objectors (COs) had faced many trials during the war, especially those whose opposition to war was secular, not religious, but the war’s end did not bring about an end to their difficulties. All of the major national peace groups of the era had expressed strong political sentiment since 1898 against U.S. imperialist incursions, along with burgeoning interest about the new communist experiments in Russian and Eastern European “soviets” (which were established in 1923). Despite their politics, all these peace groups were religiously based. Hughan and her comrades realized the great need for a secular antiwar organization that would support those objectors whose main principle against fighting did not merely derive from a theological standpoint. The new “league” became a section of War Resisters’ International, a then-new European-based secular pacifist group. Hughan served as the organization’s chief funder and director, also serving for decades on the organization’s executive committee; during much of this time, the organization’s sole paid staffer was its Executive Secretary, the redoubtable Abe Kaufman.

1923 was a pivotal year in many respects. A failed coup attempt in Germany landed its young leader—one Adolf Hitler—in jail. In Florida, the “Rosewood Massacre” saw an entire town burned to the ground by the Ku Klux Klan, but further north an intense explosion of interest in jazz brought trumpeter Louis Armstrong to global prominence. The U.S. Attorney General confirmed that it was legal for women to wear trousers in public, but Pan-African leader Marcus Garvey was sentenced to five years behind bars for mail fraud. Time magazine was launched, King Tut’s tomb was opened, Yankee Stadium hosted its first baseball game, and people were playing with that crazy new invention: the battery-operated portable radio.

Fast forward 90 years:

Organizers Ali Issa and Kimber Heinz are frantically texting their contacts in Bahrain and Palestine, in Iraq and Chile and Indian Country, USA, from their cramped corners in the WRL national office. In one hand (practically one thumb), their mobile phones connect them to the sounds, words, images, and people around the world who make up the recently launched Facing Tear Gas campaign. Though some WRL long-timers raise concerns about mobilizing against just one small tool of the war machine when so much needs to be done to shut down “the whole damn thing,” Kimber and Ali are in on an important fact apparently evi dent to many of their younger generation: The Made-in-America tear gas used throughout the planet to explicitly contain and suppress popular street demonstrations is a particularly effective symbol of increasing repression in the face of dramatic 21st-century nonviolent resistance movements. By working against the sale and use of the toxic chemical weapon—always understood as the tip of the military iceberg—WRL organizers have brought folks together across geographic, cultural, and political boundaries. Their portable gizmos spread the word about the need to resist repression, war, and all the causes of war to a far-flung series of organizers the world over, all at a speed unimaginable to Mama Jessie Hughan.

dent to many of their younger generation: The Made-in-America tear gas used throughout the planet to explicitly contain and suppress popular street demonstrations is a particularly effective symbol of increasing repression in the face of dramatic 21st-century nonviolent resistance movements. By working against the sale and use of the toxic chemical weapon—always understood as the tip of the military iceberg—WRL organizers have brought folks together across geographic, cultural, and political boundaries. Their portable gizmos spread the word about the need to resist repression, war, and all the causes of war to a far-flung series of organizers the world over, all at a speed unimaginable to Mama Jessie Hughan.

What has enabled this rag-tag group of iconoclasts, this contentious group of visionaries, to stay around long enough to now be heralded as the nation’s oldest secular peace association? What holds together this ideologically diverse group of socialists, anarchists, and others, who refuse to go to war with anyone including one another, and who settle their differences on the sports field at occasional anarchist-versus-socialist softball games? What motivated Albert Einstein to agree to the title of WRL Honorary Chair and declare boldly at a 1930 meeting of the organization that, “even if only two percent of those assigned to perform military service should announce their refusal to fight, governments would be powerless”?

Perhaps it was the same impression that motivated Nobel Peace Laureates Archbishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa, former Timor-Lest (East Timor) President José Ramos Horta, and Mairead Corrigan Maguire of Northern Ireland to provide video messages commemorating WRL’s 90th birthday celebration as part of the “I Choose Peace” campaign, explaining why they became peacemakers. It is the same spirit inspired Toshi and Pete Seeger to exclaim: “If the human race is still here in 2111, the War Resist- ers League will be one of the reasons why!”

One clue about WRL’s longevity is surely the ability to mix, sometimes uncomfortably, a principled radical vision with an understanding of the need for tactically reformist organizing efforts. Even though Hughan was a committed socialist, for example, and ran for office many times as a candidate of the Socialist Party, it is significant that the WRL’s origins were marked by an emphasis on individual acts of non-compliance. Throughout its early years, its motto was “Wars will cease when men refuse to fight.”

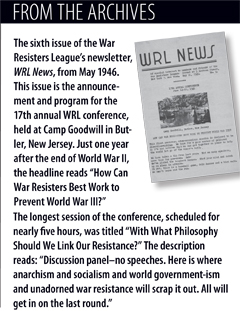

Soon after its founding, WRL faced its first crisis when the war drums began again for what would come to be known as “the Good War.” A far more popular war than the great “war to end all wars,” WWII was seen by most as the best way to fight fascism and dictatorship, and non-military resistance to evil was an idea with few followers. Despite the work of WRL in its first ten years, the only conscientious objection recognized by the U.S. government as acceptable grounds for exemption from conscription was that based on religious beliefs; further, even officially recognized COs were only exempted from combat action and were “drafted” into civilian service. Thus, political secular pacifists were unrecognized as such and unable to officially opt out of the entire war operation. A substantial number of war resisters spent their war years in federal prisons.

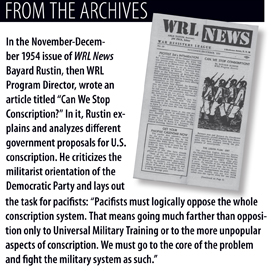

Many of those had held radical ideas before the war—but their prison terms further sharpened their politics. For one thing, imprisoned together, they formed a tightly knit community which for most of them had been unprecedented. For another, there were aspects of prison life that they found highly objectionable, chiefly including strict racial segregation even behind bars. Some of the jailed pacifists who would become most well known for their staunch resistance to segregation in future years became widely respected leaders within WRL and the movement as a whole. These pioneers included eventual WRL staffers Igal Roodenko and Ralph DiGia, civil rights and antiwar coalition-builders Bayard Rustin and Dave Dellinger, iconic war tax resistance leader Wally Nelson, and Pan-Africanists Bill Sutherland and George Houser.

Many of those had held radical ideas before the war—but their prison terms further sharpened their politics. For one thing, imprisoned together, they formed a tightly knit community which for most of them had been unprecedented. For another, there were aspects of prison life that they found highly objectionable, chiefly including strict racial segregation even behind bars. Some of the jailed pacifists who would become most well known for their staunch resistance to segregation in future years became widely respected leaders within WRL and the movement as a whole. These pioneers included eventual WRL staffers Igal Roodenko and Ralph DiGia, civil rights and antiwar coalition-builders Bayard Rustin and Dave Dellinger, iconic war tax resistance leader Wally Nelson, and Pan-Africanists Bill Sutherland and George Houser.

With techniques they had learned from the acts of Indian independence leader Mohandas Gandhi, they used hunger strikes and work stoppages, combining education of their fellow inmates and guards and direct action across racial lines. They did all this while incarcerated for resisting a hugely supported war—and they won! The federal government shortly thereafter desegregated the dining rooms in a number of prisons.

Buoyed by these victories and their deepened camaraderie, they were not about to give up these connections once the war was over and they were released from federal custody. Refusing to fight was no longer enough for them; they wanted to oppose war, its allied institutions, and the structures that uphold them. They set up intentional communities (including two renowned print shops that helped publish special works by such notable up-and-coming authors as Jack Kerouac). Some of them formed collective living arrangements that they called “ashrams” from the Indian model; the Harlem Ashram—challenged by Puerto Rican Nationalist Party leader Pedro Albizu Campos, who was recovering from cancer contracted during a prison term of his own—shifted focus to become the leading North American supporters of that Caribbean-based independence movement so much closer to home.

Early and inspirational efforts against the Cold War took shape with the building of a Peacemakers war-tax resistance project. Meanwhile, four of these resisters—Dellinger, DiGia, Sutherland, and Quaker CO Art Emery—made plans to bicycle from Paris across Europe all the way to Moscow in order to warn the world of the dangers of atomic warfare. Another new series of actions focused on resistance to the so-called “civil defense drills.” In schools across the country, children were regularly taught to hide under their desks in the event of nuclear attack, and urban centers mandated absurd and futile drills, during which the public was required to practice surviving an atomic bomb by taking shelter in basements and subway stations. In New York City, members of WRL and the Catholic Worker, led, respectively, by DiGia and Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day, stood in City Hall Park and refused to take shelter. They were arrested and jailed, but the city eventually yielded to their resistance and ceased holding the drills. And among its educational efforts, WRL also helped launch Liberation magazine, which became the most significant publication of its time explicating and promoting Gandhian nonviolence.

It is hardly surprising that the released COs had re-entered the outside world committed with great fervor to the fight against racism and for equality. In 1947, sixteen men—eight white, eight Black—undertook the country’s first Freedom Ride, a “Journey of Reconciliation,” under the aegis of the newly formed Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and supported by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) through their staff members Rustin and Houser. Six of the sixteen—Rustin, Houser, Roodenko, Nelson, Joe Felmet, and “Freedom Ride” author Jim Peck, who continued to participate in the civil rights movement for two decades—were or would be closely involved with WRL. Rustin, forced off of the FOR staff after an arrest in California for “sex per- version,” joined WRL as its Executive Secretary, playing a key role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, working as chief strategist and mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. While on leave from WRL due to a special arrangement worked out among King, Rustin, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters President A. Philip Randolph, pacifist leader A.J. Muste, and WRL Chair Roy Finch, Rustin served as coordinator of the great March for Jobs and Freedom which brought 100,000 people to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963.

It is hardly surprising that the released COs had re-entered the outside world committed with great fervor to the fight against racism and for equality. In 1947, sixteen men—eight white, eight Black—undertook the country’s first Freedom Ride, a “Journey of Reconciliation,” under the aegis of the newly formed Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and supported by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) through their staff members Rustin and Houser. Six of the sixteen—Rustin, Houser, Roodenko, Nelson, Joe Felmet, and “Freedom Ride” author Jim Peck, who continued to participate in the civil rights movement for two decades—were or would be closely involved with WRL. Rustin, forced off of the FOR staff after an arrest in California for “sex per- version,” joined WRL as its Executive Secretary, playing a key role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, working as chief strategist and mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. While on leave from WRL due to a special arrangement worked out among King, Rustin, Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters President A. Philip Randolph, pacifist leader A.J. Muste, and WRL Chair Roy Finch, Rustin served as coordinator of the great March for Jobs and Freedom which brought 100,000 people to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in August 1963.

Yet, as WRL celebrates its 90th anniversary and the world remem- bers the 50th anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, many of the basic goals shared by the WWII COs remain unmet.

Clearly, a new militancy had infused the nonviolent war resistance movement, as Gandhian nonviolence began to be discussed with great fervor. There were those among the WRL “old guard” who believed that the Gandhian perspective, including an emphasis on civil disobedience, direct action, and constructive programs, exceeded the mandate of secular pacifism. In addition, it was clear that the U.S. COs were taking their radical ideas to new levels that would eventually influence the entire left, as the Committee for Nonviolent Revolution was formed.

They noted: “We know that Revolution means using the general strike, the sit-down strike, mass civil disobedience, to seize control from private owners, state bureaucrats and fake labor czars.” Their call for future direction was clear: “This is the Era of One World and Two Classes: we must attack war and inequality directly!”

1955 was the ultimate turning point. Muste resigned from the WRL executive committee following Rustin’s dramatic 1953 hire (for background scoop, see WRL’s online slideshow on Rustin, Building Bridges through Revolutionary Nonviolence), and Finch—another WWII CO who was part of this direct action tendency—was named Chair of the organization. DiGia was hired as WRL’s Administrative Secretary, a post in which he would essentially remain for a remarkable 50-plus years. And Jessie Wallace Hughan, who had in many ways supported the new generation of WRL leaders and staff people, passed away suddenly following a stroke. WRL had transitioned into a vibrant, action-oriented core group of now-experienced resisters, holding onto its pacifist principles but open to taking on U.S. imperialism—along with the roots of war—in much more confrontational ways.

The period we have come to think of as “the Sixties” began in earnest in the mid-1950s. The widespread, Southern-based, Black-led Freedom movement, coupled with the movement against the Korean “police action” and the much more massive anti-Vietnam war movement, had their roots in the boycotts, sit-ins, and antiwar vigils in which WRL took part in during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Staff member David McReynolds, who himself served a remarkable 40-year career with WRL, was among the first to burn his draft card in a 1965 demonstration just a year after the Tonkin Gulf resolution made the conflict in Southeast Asia national news in the United States. To many, the fight for “civil rights” and opposition to war remained separate efforts, united only by the interest they held in both struggles. But over the following ten years, a new generation of resisters would again assert and insert themselves into the organizational politics of WRL and the body politic of the nation. Though it would be several decades before WRL began to accept the inextricable tie between racial injustice and the behemoth of the military industrial complex as a core organizing principle, the roots for this analysis had its foundations in this era.

The period we have come to think of as “the Sixties” began in earnest in the mid-1950s. The widespread, Southern-based, Black-led Freedom movement, coupled with the movement against the Korean “police action” and the much more massive anti-Vietnam war movement, had their roots in the boycotts, sit-ins, and antiwar vigils in which WRL took part in during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Staff member David McReynolds, who himself served a remarkable 40-year career with WRL, was among the first to burn his draft card in a 1965 demonstration just a year after the Tonkin Gulf resolution made the conflict in Southeast Asia national news in the United States. To many, the fight for “civil rights” and opposition to war remained separate efforts, united only by the interest they held in both struggles. But over the following ten years, a new generation of resisters would again assert and insert themselves into the organizational politics of WRL and the body politic of the nation. Though it would be several decades before WRL began to accept the inextricable tie between racial injustice and the behemoth of the military industrial complex as a core organizing principle, the roots for this analysis had its foundations in this era.

As the first peace group to call for U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam, WRL played a key role for all the years the war lasted, organizing what became mass draft card burning events, coordinating major rallies, and initiating civil disobedience actions at induction centers throughout the country. In New York City, the WRL-led Fifth Avenue Peace Parade Committee—co-convened by Muste (who continued to work with the organization) and Norma Becker (one of the few women spokespeople for the coalitions of the time, later to become WRL Chair)—brought tens of thousands of opponents of the war into the streets. League members traveled illegally to North Vietnam and wrote about their journeys in Liberation. More risky yet, WRL members and staffers were key activists in the new “Underground Railroad” that, when necessary, helped draft resisters find refuge outside the United States. WRL staffer Karl Bissinger, who had had a flourishing career as a photographer known for his stunning portraits of U.S. writers and artists, gave it up completely to devote himself to working for peace; years later his Luminous Years: Portraits at Mid-Century, with striking images of writers like James Baldwin and French novelist Colette and actors like Katherine Hepburn and Marlon Brando, among many others, enjoyed a foreword by Gore Vidal upon its 2003 publication. Working with the Greenwich Village Peace Center, Bissinger devoted himself to helping thousands of young men avoid serving in Vietnam, up to and including helping them leave the country if that was their only way out of the Army. With close friend activist-writer Grace Paley (whose lifelong political home was WRL), award-winning children’s book illustrator Vera Williams, and poet Sybil Claiborne, Bissinger brought the community of young draft resisters and their allies into the WRL when the war ended in 1975.

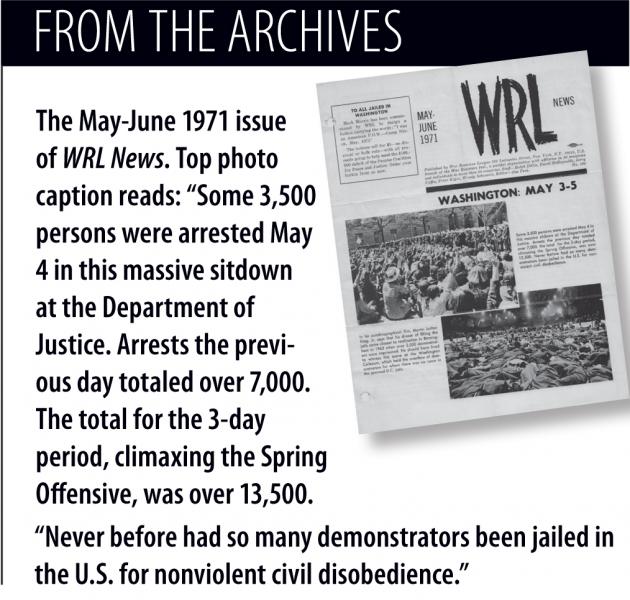

As all the peace and justice organizations and organizers of “the Sixties” faced the challenge of how to remain relevant and exciting in the wake of widespread exhaustion, of cooptation and confusion, of disillusionment in the face of the assassinations of King and others (and the conclusion by some that nonviolence was no longer a viable technique for revolutionaries), this new generation of WRL activists attempted to take heart in the small, grassroots collectives that remained true to their long-term political goals. Surrounded by a much-shared sentiment at the end of the war that revolution in the United States might be “just around the corner,” energized by the successful national liberation movements abroad and unexpected victories at home (including the downfall of two successive Presidents), some took their inspiration from the huge demonstrations they were able to build. Even as central coalition coordinator Dave Dellinger was under indictment and trial as part of the Chicago Conspiracy case stemming from a 1968 police riot at the time of the Democratic Party National Convention, significant mobilizations took place with WRL and young draft resistance leadership, 500,000 attended the 1969 March Against Death, a national moratorium against the war that swept through many communities in 1970, and the 1971 May Day Protests—coordinated by WRL’s Jerry Coffin—involved militant mass actions to try to “shut down the government.” A record 12,614 people were arrested in well-orchestrated nonviolent civil disobedience.

As all the peace and justice organizations and organizers of “the Sixties” faced the challenge of how to remain relevant and exciting in the wake of widespread exhaustion, of cooptation and confusion, of disillusionment in the face of the assassinations of King and others (and the conclusion by some that nonviolence was no longer a viable technique for revolutionaries), this new generation of WRL activists attempted to take heart in the small, grassroots collectives that remained true to their long-term political goals. Surrounded by a much-shared sentiment at the end of the war that revolution in the United States might be “just around the corner,” energized by the successful national liberation movements abroad and unexpected victories at home (including the downfall of two successive Presidents), some took their inspiration from the huge demonstrations they were able to build. Even as central coalition coordinator Dave Dellinger was under indictment and trial as part of the Chicago Conspiracy case stemming from a 1968 police riot at the time of the Democratic Party National Convention, significant mobilizations took place with WRL and young draft resistance leadership, 500,000 attended the 1969 March Against Death, a national moratorium against the war that swept through many communities in 1970, and the 1971 May Day Protests—coordinated by WRL’s Jerry Coffin—involved militant mass actions to try to “shut down the government.” A record 12,614 people were arrested in well-orchestrated nonviolent civil disobedience.

The structure of these actions helped pave the way for the next major wave of peace action: work attempting to link the social justice campaigns and the general anti-weapons sentiments of the previous era. In 1976, the WRL-initiated Continental Walk for Disarmament and Social Justice brought together antiwar draft resisters, Black community activists, Japanese anti-A Bomb campaigners, and a host of others in an alternative to the nation’s bicentennial hoopla. The decentralized nature of the walk, combined with the affinity group formations that had been successfully utilized in the civil disobediences of the late 60s and early 70s, proved instrumental in the work at the end of the decade, as the rise of nuclear power technology sparked a series of “shut them down” protests. Dramatic protests—such as the simultaneous antinuclear civil disobedience protests held on the White House front lawn and in the center of Moscow’s Red Square—marked the creative contributions of WRL to the wider movement. Tactical disagreements rose up throughout this period (about whether opposition to nuclear power should be linked to nuclear weapons, whether a call for unilateral U.S. disarmament was prudent, and whether a nuclear “freeze” would be more strategic than calling for full disarmament). But WRL held to a firm position of radical nonviolence, playing a crucial role in strengthening the multi-issue Mobilization for Survival, building for the million-strong June 12, 1982, UN/Central Park peace demonstration—coordinated by WRL 90th anniversary conference coordinator Leslie Cagan—which remains the largest in U.S. history, and initiating the June 14 simultaneous civil disobedience actions at the UN missions of all five admitted nuclear powers.

From founders to WWII COs to “the Sixties,” the WRL of the 1980s was poised to accept the challenges of a new grouping of “combative pacifists,” as Grace Paley often called herself. This group, in which Paley held a leading part, took note of the critiques and the realities of people like Barbara Deming and untold lesser-known women, whose behind-the-scenes work was never questioned as anything less than essential but whose acceptance as movement leaders or “heavies” was never forthcoming. With the possible exception of Norma Becke r, the norm was for the men—of WRL and most peace groups—to serve as spokespeople and representatives and key authors, despite a vast array of vital theoretical texts penned by women. (The exceptions were those groups that explicitly called themselves women’s organizations, like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom—WILPF—co-founded by Nobel Laureate Jane Addams, and Women Strike for Peace, founded by Dagmar Wilson and future U.S. Congressional Representative Bella Abzug.) A young draft registration resister of the early 1980s (such as one of this article’s co-authors) could hardly attend a meeting without warnings from feminist activists and from Black Vietnam veterans not to repeat the mistakes of the past: by giving in through omission or commission to the Left’s version of racism and sexism.

r, the norm was for the men—of WRL and most peace groups—to serve as spokespeople and representatives and key authors, despite a vast array of vital theoretical texts penned by women. (The exceptions were those groups that explicitly called themselves women’s organizations, like the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom—WILPF—co-founded by Nobel Laureate Jane Addams, and Women Strike for Peace, founded by Dagmar Wilson and future U.S. Congressional Representative Bella Abzug.) A young draft registration resister of the early 1980s (such as one of this article’s co-authors) could hardly attend a meeting without warnings from feminist activists and from Black Vietnam veterans not to repeat the mistakes of the past: by giving in through omission or commission to the Left’s version of racism and sexism.

Organizationally speaking, however, it was the push from feminists that would carry the day within WRL.

The Second Wave of feminism grew in part out of the increasing awareness by women in the antiwar movement of the ways in which they were relegated to subordinate roles; its impact on the antiwar and corollary movements is incalculable. The movement gave birth not only to a quantum leap in women’s leadership but also to feminist-influenced organizing models, styles, and content; other movements, in the United States and around the globe, were undoubtedly also affected. It can be said, indeed, that from the early 1970s on, an ever-widening range of women-led actions and campaigns, and feminist-influenced processes, birthed a great multi-centered web of resistance. One nexus of this began with the women’s movement in the United States and carried on to the lesbian and gay liberation movement; today it extends across the globe.

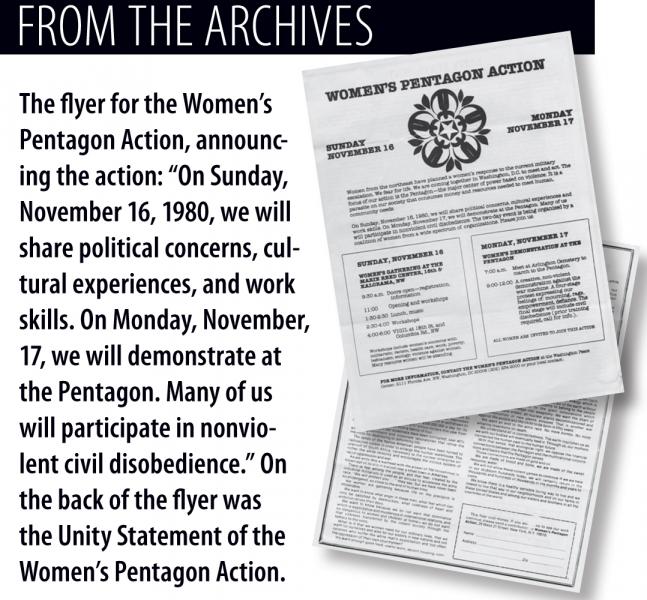

In hindsight, it should not be surprising that a 1975 War Resisters’ International (WRI) decision to hold a gathering specifically for women peace activists was bitterly controversial. Many in WRI (of which the WRL is the chief U.S. affiliate) refused to believe that women should meet separately at all! But this early “caucus” space helped WRI, its affiliates, and the international peace movement realize that a conscious feminist presence could only enhance the nonviolence movements. Developing human rights and environmental movements, parts of which merged with the antiwar movement as they grew, owed much—for example—to feminist perceptions of the earth and the human community. It was the 1980 Women’s Pentagon Action in Washington DC that really set the standard for new thinking and a renewed spirit of revolutionary action.

The Women’s Pentagon Action statement—part poetry, part outcry, part call to resist—is as poignant now as it was then. With painted banners and huge puppets designed by Vermont’s Bread and Puppet Theater, they proclaimed “no more amazing inventions for death” and wove webs around one another and around the doors of the center of U.S. military madness, symbolically chaining them shut. “We have come here to mourn and rage and defy the Pentagon,” they wrote in collective fashion, “because it is the workplace of imperial power which threatens us all. Every day while we work, study, love, the colonels and generals who are planning our annihilation walk calmly in and out the doors of its five sides…”

“There is a fear among the people, and that fear, created by the industrial militarists is used as an excuse to accelerate the arms race. ‘We will protect you…’ they say, but we never have been so endangered, so close to the end of human time.

“There is a fear among the people, and that fear, created by the industrial militarists is used as an excuse to accelerate the arms race. ‘We will protect you…’ they say, but we never have been so endangered, so close to the end of human time.

“We women are gathering because life on the precipice is intolerable.

“We want to be free from violence in our streets and in our houses. The pervasive social power of the masculine ideal and the greed of the pornographer have come together to steal our freedom, so that whole neighborhoods and the life of the evening and night have been taken away from us. For too many women the dark country road and the city alley have concealed the rapist. We want the night returned, the light of the moon, special in the cycle of female lives, the stars and the gaiety of the city streets.

“We have the right to have or to not have children, we do not want gangs of politicians and medical men to say we must be sterilized for the country’s good. We know that this technique is the racist’s method of controlling populations. Nor do we want to be prevented from having an abortion when we need one. We think that this freedom should be available to poor women as it has always been available to the rich. We want to be free to love whomever we choose. We will live with women or with men or we will live alone. We will not allow the oppression of lesbians. One sex or one sexual preference must not dominate another.

“We do not want to be drafted into the army. We do not want our young brothers to be drafted. We want them equal with us…

“We understand that all is connected. The earth nourishes us as we with our bodies will eventually feed it. Through us, our mothers connected the human past to the human future.

“With that sense, that ecological right, we oppose the financial connections between the Pentagon and the multi-national corporations and banks that the Pentagon serves.

“These are connections made of gold and oil. We are connections made of blood and bone, we are made of the sweet and finite resource, water.”

The Women’s Pentagon Action did not unite all the women in WRL or on the Left, nor did it end patriarchy or even poor treatment of women in the movement. But it set forth a space where leaders such as Susan Pines and Mandy Carter, Joanne Sheehan and Kathy Engel, Wendy Schwartz and Norma Becker, and countless others (including perhaps one of the authors of this piece) could more easily exercise degrees of power and influence proportionate to their creative work and ideas.

One of the sharpest lessons of the Sixties upsurge learned and applied by the U.S. government and military apparatus was to keep wars short, “low intensity,” economic, psychological and cultural if possible—and by any and all means to restrict media coverage. Divide and conquer in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond was the aim of FBI Counter-Intelligence Programs, targeting, disrupting, imprisoning, and assassinating key movement figures; the government made sure that efforts against intervention in El Salvador were not quite in sync with those supporting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, who in turn would be kept quite separate from those close to Grenada’s New Jewel Movement.

One of the sharpest lessons of the Sixties upsurge learned and applied by the U.S. government and military apparatus was to keep wars short, “low intensity,” economic, psychological and cultural if possible—and by any and all means to restrict media coverage. Divide and conquer in the 1980s, 1990s, and beyond was the aim of FBI Counter-Intelligence Programs, targeting, disrupting, imprisoning, and assassinating key movement figures; the government made sure that efforts against intervention in El Salvador were not quite in sync with those supporting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, who in turn would be kept quite separate from those close to Grenada’s New Jewel Movement.

Beyond the divisions in the Central America solidarity movement, there were few consistent connections among the anti-apartheid movement, the Southern Africa solidarity movement, groups for Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific, those for Soviet and/or Chinese “friendship,” for an end to war in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya. More to the point, as disconnected from each other as all of these internationally oriented movements were, they were all even more separated from those working on “domestic” issues, whether defined as human needs, Black liberation, Mexican reunification and New Afrikan independence, welfare rights, educational equity, or a dozen dozen other “progressive” causes. Veteran activist Dave Dellinger always reflected that the sheer numbers of people in the United States working for positive, often radical social change was far, far greater in the 1980s and 1990s than at any point in the tumultuous 60s or 70s. The groups were just more diffuse, spread out, or uncoordinated.

Thus, work within WRL at times seemed similarly unfocused, with educational efforts, organizing packets, and campaigns often seemingly jumping from one “issue” to the next. Much good work was done, and many connections with diverse peoples making lifetime commitments and life-long changes were undoubtedly made. In hindsight, however, the WRL did little better than the rest of the Left in building a consistent program against war or the roots of war.

In the mid-1990s, however, the WRL National Committee made a decision that would have far-reaching consequences. A large bequest from WWII CO (and Journey of Reconciliation veteran) Joseph Felmet made it possible for the organization to plan its future with much more security. With the Felmet bequest, WRL decided to structure its organizing more than it ever had in the past—in effect, to create an organizing program that would set its own goals and campaigns. As the first step in that process, it decided to create as a formal program a new, broader version of its antiwar toys campaign, a campaign that would reach out to young people, and to hire another staff person to be its youth organizer. Since the mid-1980s, there has been a concerted effort to bring younger people into the League’s National and Executive committees.  The publication of S.P.E.W. ‘zine (with a mutable acronym which could stand for “Support Peace, End War,” “Smash Patriarchy EveryWhere,” or a myriad of other slogans), aimed to entice a new generation of war resisters using vivid graphics; ex- clusive interviews with hip hop pioneers Stetsasonic, Frank Zappa, youth activists, and others; give-away stickers, and short articles which could be made into do-it-yourself flyers.

The publication of S.P.E.W. ‘zine (with a mutable acronym which could stand for “Support Peace, End War,” “Smash Patriarchy EveryWhere,” or a myriad of other slogans), aimed to entice a new generation of war resisters using vivid graphics; ex- clusive interviews with hip hop pioneers Stetsasonic, Frank Zappa, youth activists, and others; give-away stickers, and short articles which could be made into do-it-yourself flyers.

But the intensified focus on youth brought into WRL’s formal program work a strain of thought that had been per- colating within the organization for some time: that in the United States, the youth most affected by war were those who in fact were subject to the “poverty draft.” The economic factors that force poor young people into the military, especially young people of color, are indelibly linked to the economic factors that cause war itself—from war profiteers to corrupt politicians to an economic system that requires war, poverty, and racism in order to thrive and create expansive wealth for the few. These were hardly new thoughts within WRL. What was new—and would profoundly affect WRL’s course over the next two decades—was that, for the first time, issues of poverty and race had become the explicit foundation of a substantial part of its work.

Moreover, the focus on youth and on the impact of militarism on youth of color necessarily brought onto the WRL staff a new influx of talented, energetic young organizers, many of them from communities not traditionally represented in the Old Left, predominantly Eurocentric peace organizations. Commitment to anti-imperialism and antiracism—resistance to the systemic structures of inequality that underlie so many facets of U.S. life—began to replace the notion of patchwork struggles for human rights or vague notions of reversing the arms race. And the phrase “revolutionary nonviolence”—still in need of greater clarification and synthesis—was brought to the masthead of WRL’s newly re-named WIN magazine. The Summer 2006 issue laid out the reasons for the title change. The editorial committee, led by the magazine’s dynamic new editor Francesca Fiorentini, wrote:

“Today, nonviolence again faces challenges. Oftentimes, it is articulated in abstract or inaccessible ways, appearing removed from ‘on the ground’ struggles. Nonviolence needs to be shaken from this philosophical slumber, to breathe fire once more. WIN magazine hopes to help rekindle this fire and contribute to building a vibrant and inclusive nonviolent movement.

“After all, nonviolence is not just a pleasant-sounding philosophy, but a revolutionary practice to be realized in context, with eyes wide open. It is not a fixed ideology, but is dynamic—attentive to and shaped by the world around it.

Nonviolence must be courageously complex, making space for dialogue and disagreement. It is not a map, but a walking stick—guiding us on our long journey, transformed by the trail blazed…

“WIN will explore the cracks in this empire that are bringing us closer to the just world in which we have yet to live—from free health clinics and collective childcare, to alternative economic systems and alternative energy. Each season, WIN will harness this revolutionary imagination, bringing you stories from a movement bold enough to act and smart enough to dream.”

Which brings us to the Tear Gas campaign, to the 2013 WIN issue on health, and to much of WRL’s work today. As noted on the Facing Tear Gas web site of the new WRL campaign, outlawing the use of a single chemical weapon, even as insidiously deadly and directly repressive and anti-democratic a weapon as tear gas, is far from the major goal. The campaign seeks to raise consciousness and political action about the connections between the military, the police, and the ever-expanding prison industrial complex; it seeks to bring together a broad grouping of people around the world in a network that can share skills, information, experiences, and resources, to turn around the fear and isolation caused by intense anti-movement repression. A testimonial by “Zacariah” posted on the Campaign website recalled: “In 1991, I was gassed in Occupied Palestine by the Israeli Defense Force, as I was on my way to school as a 6 years old [child]. In 2011, I was gassed in Oscar Grant Plaza by [California’s] Oakland Police Department as I was peacefully occupying at the Intifada Tent. Everyone on that bright and sunny day in Ramallah and that cold and sleepless night in Oakland says ‘No More Tears.’”

The picture of WRL has changed—radically, so to speak. The history of how we got from there to here, from “Wars will cease when men refuse to fight” to “revolutionary nonviolence,” is a long and rich one. We have provided only the broadest outline of that history here—the story of turning points, of an ever-widening perception. WRL today is rooted in the conviction that wars will cease only when all people refuse to fight, and also when all people refuse to cooperate with the immensely unjust and multifarious structures which create war, when we work actively and unceasingly to oppose them. If WRL still has a ways to go to be fully relevant and effective in the 21st century—and no doubt it does—it has nevertheless come so far in its first ninety years as to suggest that it has a good chance of meeting even that ambitious goal.

This piece first appeared in WIN Magazine, Summer/Fall 2013. Follow this link for a piece that was created for WRL’s 100th anniversary, and check out our Centennial History Blog posting weekly during our 100th year

Share