During the Vietnam War era, between 1964 and 1973, the U.S. military drafted 2.2 million men out of an eligible pool of 27 million. Of those, 16.3 percent were Black. Of Vietnam combat troops, 23 percent were Black. Indeed, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. referred to the Vietnam War as a white man’s war, a black man’s fight.

As one of many anti-draft campaigns, the national New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam called for Anti-Draft Week actions, March 16-22, 1970, with nonviolent civil disobedience at draft boards around the country on March 19th.

At age 22, I was thrilled to join the WRL staff collective—as its first woman member in many years. (I had begun my tenure on the WRL staff as David McReynolds’ secretary, who was on leave. At the time, no one thought that this position was inappropriate.) My first major assignment was to represent WRL on the March 19th CD action committee, comprised of representatives from local NYC groups.

At age 22, I was thrilled to join the WRL staff collective—as its first woman member in many years. (I had begun my tenure on the WRL staff as David McReynolds’ secretary, who was on leave. At the time, no one thought that this position was inappropriate.) My first major assignment was to represent WRL on the March 19th CD action committee, comprised of representatives from local NYC groups.

One morning a police detective came to our office asking about the planned anti-draft CD. Directed to my cubicle, he settled in the chair usually reserved for my draft counselees. “Call me Ray,” he said. “I found out about WRL through Dial-a Demonstration. I call every day.” Telephones were the only way to communicate information quickly then, and folks who wanted to know about upcoming antiwar actions called Dial-a-Demonstration for a recorded list. Apparently, the police also found this service useful.

Ray and I began a relationship that involved my answering his questions as long as the information was public knowledge. He was polite and friendly, never commented about the war, the posters on the walls, or anything else not concerning the impending CD.

Shortly before March 19th, a small delegation from the CD action committee went to the police headquarters covering our target, the Varick Street Induction Center, to report our plans and discuss logistics. I was very nervous, and therefore pleased to see that the others in our delegation were experienced negotiators, so I wouldn’t have to say much.

We all sat around a long beautiful mahogany table — so shiny we could almost see our faces in it. One member of our group, known for her maternal approach to the antiwar movement and wanting to break the ice, reached into a bag and said “we should share a snack.” Out came several oranges which she began to peel. As she passed around slices, to the clear perplexity of the high ranking police at the table, I could focus only on the mess on the table: sticky juice, seeds, rinds, membranes. No one commented, but few took a slice. Somehow we all established the scenario for the arrests and left, our group to head to the subway, the police to deal with their table.

The weather on demonstration day was fine, and 500 protesters arrived at the Induction Center early in the morning. Those of us willing to be arrested—182, it turned out—lined up, walked to the closed Center door, and were escorted to a waiting bus by police officers. After a few hours in a holding cell we were released on our own recognizance.

The weather on demonstration day was fine, and 500 protesters arrived at the Induction Center early in the morning. Those of us willing to be arrested—182, it turned out—lined up, walked to the closed Center door, and were escorted to a waiting bus by police officers. After a few hours in a holding cell we were released on our own recognizance.

A debate in WIN Magazine ensued between David McReynolds and a very angry Steve Suffitt. Steve called the CD action an “obscenity” because its goal was to get arrested and was discussed with the police in advance; it was not to simply court arrest and see how the police responded, which he would have preferred. David responded that telling the police what we were going to do is “one of the things that nonviolence is about.” Of course, different circumstances, and different policies and practices, to resist require different tactics. Some surely warrant no prior communication with police. But this anti-draft action, I believe, was organized and conducted correctly. I was proud to have helped make it happen.

Several days after the action, Ray appeared once again in my cubicle. “Wendy,” he said ruefully, “why didn’t you tell me you were going to be arrested?” “I thought you would assume it, and, anyway, how could I lead others to jail and not risk it myself?” I responded. “It was the only moral and ethical thing to do.” He shook his head, still looked a little puzzled, but smiled finally.

After years of work by many thousands of people from all parts of American life the draft was ended. Unfortunately, however, there is a new effort to revive the potential for conscription. Indeed, recently the U.S. Senate joined the House of Representatives in an attempt to "automatically" register all draft-eligible citizens and residents for a possible military draft.

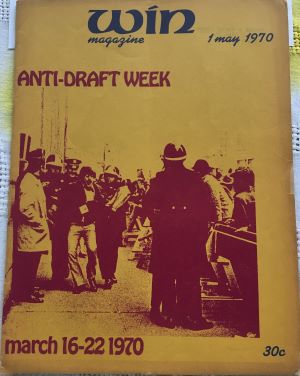

Photos by Lana Reeves from May 1, 1970 issue of WIN (Vol. 6, #8), including Cover and photos from “Anti-draft Week, March 16-22, 1970” by David McReynolds

(from top to bottom):

Anti-Draft Week headline

Cover of May 1, 1970 issue of WIN (Vol. 6, #8)

Grace Paley, chief organizer of the demonstration

End the War Now sign at 1970 Anti-Draft Week action

Police at 1970 Anti-Draft Week action

Wendy Schwartz

Wendy has served WRL in multiple roles for over 50 years. Sometime after this demonstration, she joined two men and another woman in a public draft card burning on Long Island. A conviction for draft card burning carried a five-year prison sentence regardless of the gender of the burner or whether the cards burned belonged to the burner. FBI agents were present at the action and took photographs, but none of the four was ever contacted about it.